|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 13(5); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Neck pain is a common condition with several proposed biomechanical contributing factors. Thoracic spine dysfunction is hypothesized as one of the predisposing factors, which necessitates the need to explore the contribution of thoracic posture and mobility toward neck pain. Accordingly, the present work aimed to review the existing literature investigating the presence of thoracic spine dysfunction in individuals with neck pain. A literature search was conducted in the three electronic databases of PubMed, CINAHL, and Web of Science. Studies published between 1990 and 2017 were considered. After reviewing the abstracts, two authors independently scrutinized the full-text documents for their relevance. The initial search yielded 2,167 articles, of which nine studies involving comparisons of neck pain patients and healthy controls were identified for the review. Increased thoracic kyphosis was positively correlated with the presence of forward head posture but not uniformly associated with neck pain intensity and disability. Thoracic mobility was reduced in the neck pain population, and the role of thoracic kyphosis as a risk factor for pain development could not be confirmed. Thus, an association exists between thoracic kyphosis and postural alteration in the cervical spine. The review favors the inclusion of thoracic spine assessment and treatment in mechanical neck pain patients. Further studies are needed to investigate the cause-effect relationship between thoracic posture and cervical dysfunction.

Worldwide, neck pain ranks fourth among the leading causes for enduring years of disability [1]. The onset of neck pain peaks in middle age. The annual prevalence rate for the ailment exceeds 30%, and it occurs more often in females [1]. Most of the acute neck pain episodes resolve with or without treatment, but nearly 50% of the patients report recurrences and chronicity of pain [2].

Despite its high incidence, considerable variations exist in defining neck pain. The condition presents with a variable clinical course; however, mostly, it is described as ‘episodic’ or ‘recurrent’ [3]. This fact may be due to the association of the problem with numerous physical and psychosocial contributors [1]. The structural causes of neck pain have not been completely understood but are thought to be connected to a variety of anatomical structures and their interrelated functions [4]. The causative mechanisms rarely implicate a single anatomical structure and are dependent upon several contributing factors [4]. Peterson and Bergman [5] state that any event leading to altered joint mechanics or muscle functions can cause neck pain [6]. Hence, most of the complaints are categorized as ‘nonspecific’ or ‘mechanical’; in nontraumatic neck pain, the most significant contributor is poor posture [6]. Restricted segmental mobility of the cervical and thoracic regions has also been reported in people with neck pain [7].

Biomechanically, the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines are interrelated [8]. The thoracic spine column functions as a supporting base for the cervical spine and influences the cervical kinematics through the cervicothoracic junction [4]. Concomitant thoracic spine motion is necessary to produce the complete range of movements at the cervical spine, which are often reduced with changes in the normal alignment of the thoracic spine [8]. Owing to this close anatomical link, any mechanical dysfunction in the thoracic spine might produce associated changes in the cervical spine and vice versa [8]. The key postural muscles, namely trapezius, levator scapulae, and serratus anterior, have attachments spanning the cervical and thoracic regions. Postural impairments in the thoracic spine may lead to a dysfunction of these muscles [9]. Hence, changes in the thoracic alignment have been proven to alter the mechanical loading of the cervical spine [10]. Of relevance is the increased incidence of neck problems in older adults having a higher prevalence of thoracic hyperkyphosis [7]. Besides, reduced thoracic mobility has been identified as a predictor for neck and shoulder pain [4]. Further evidence of thoracic kinematics influencing the function of the cervical spine could be obtained from the fact that neck pain improves with thoracic articular treatment [11]. Thoracic thrust and nonthrust mobilizations have been shown to produce positive effects on the severity of neck pain, neck movements, and self-reported disability [11].

However, a systematic review reported conflicting results regarding the benefits of thoracic spine treatment in the management of neck pain [12]. Thus, there is a need to investigate the causative role of thoracic spine mobility and alignment in the subjects. Accordingly, studies have been conducted to assess thoracic spine function in individuals with cervical pain. Although individual studies exist, no review has comprehensively analyzed the available literature on the relationship between thoracic dysfunction and neck pain. Hence, a thorough review of the literature was performed to explore the relationship of neck pain with thoracic posture and mobility.

A systematic search of the literature was performed to investigate the presence of thoracic spine dysfunction in the cervical pain population. The databases of PubMed/Medline, CINAHL, and Web of Science were screened. The search strategy included MeSH terms “cervical pain,” “cervical spondylosis,” “cervical function” AND “thoracic kyphosis,” “thoracic hypomobility.” Papers published between 1990 and 2017 were considered. The studies were required to be published in English and involve only human subjects.

The primary author initially screened the titles and abstracts of the resulting articles. After reviewing the abstracts, two authors independently scrutinized the fulltext documents for relevance. Any difference of opinion was resolved with discussion.

Only case-control, longitudinal/cohort, cross-sectional, and observational studies were included. Inclusion of the neck pain (nonspecific/mechanical) population with or without healthy, pain-free controls was necessary. Research works assessing thoracic spinal alignment or dysfunction in subjects with cervical pain dysfunction were selected. The investigations that failed to assess the outcomes of interest, involved only healthy subjects, or did not include an adult population were excluded.

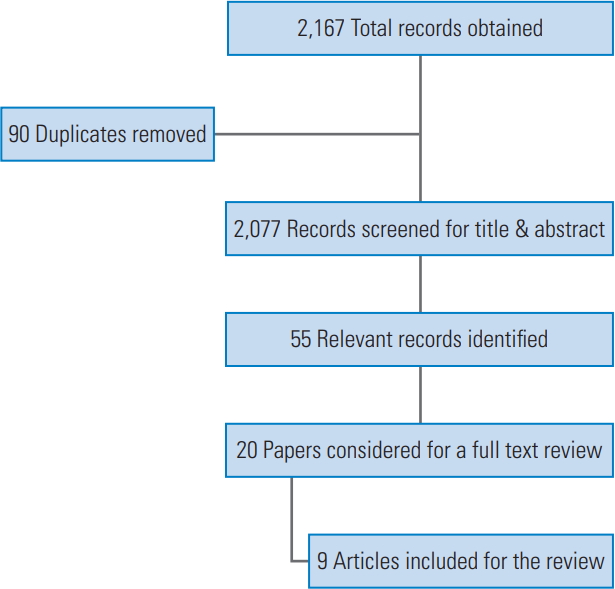

From the three databases, a total of 2,167 records were obtained. After removal of 90 duplicates, 2,077 records were screened for their titles and abstracts. Fifty-five relevant records were identified, and among them, 20 studies were considered for full-text review. Finally, nine investigations fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in this review [4,13-20] (Table 1, Fig. 1). The major reasons for exclusion were that the studies failed to measure the outcomes of interest, estimated only cervical function, involved only a healthy population, included a child/adolescent population, and comprised a whiplash-injury population.

Almost all the studies (n=9) involved participants with chronic, nonspecific neck pain. One study consisted of both acute and chronic neck pain, and another work included patients with cervical radiculopathy along with mechanical neck pain. Both male and female participants were included in seven studies, and one research study was conducted exclusively on the female population. Six out of the nine reviewed studies encompassed adults in the age group 20–50 years, whereas two studies considered elderly population above 60 years of age. Only one longitudinal study involved children (age group) and monitored them up to their adulthood. Two studies evaluated office workers involved in computer-related work and having complaints of neck pain.

Except for two studies, the rest of them mentioned the selection process of control subjects who were comparable to the cases with regard to age and gender. One of the works lacked a control group, as it was a longitudinal study on the same group.

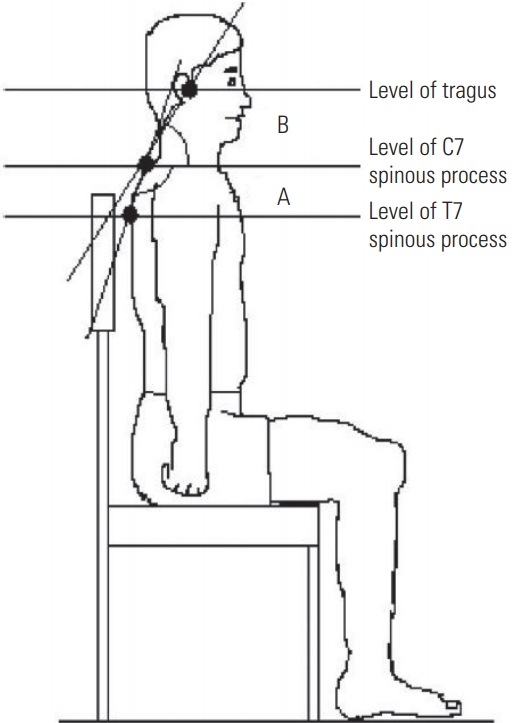

The outcomes used for assessing cervical pain and dysfunction included the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), Visual Analogue Scale for severity of neck pain, Neck Disability Index, Northwick Park Questionnaire, and other questionnaires (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, and Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey) to evaluate the associated disability. Craniovertebral angle (CVA) for cervical posture and upper/high thoracic angle (HTA) values for thoracic spine alignment were the commonly used measures of posture. CVA refers to the angle formed between a line drawn from the tragus of the ear to the seventh cervical vertebra (C7) and the horizontal (Fig. 2). Upper/HTA was calculated as the angle formed between a line joining the spinous processes of the seventh cervical and thoracic vertebrae (C7 and T7) and the horizontal (Fig. 2). One study also measured the various gait parameters and the amount of spinal rotations during walking tasks. Postural assessment outcomes were mostly evaluated through photographs, videos, software, and radiographic films.

Overall, five studies examined the influence of thoracic spine posture (upper thoracic angle [UTA]) on neck pain. A positive correlation was observed between higher UTA and neck pain by Lau et al. [4], but the thoracic kyphosis was not a significant predictor for the intensity of the neck pain as measured on NPRS. In this study, the neck pain group displayed a greater UTA (7.3°) when compared with the healthy controls. Similar results were reported by Kaya and Çelenay [19], who witnessed a positive correlation between thoracic curvature and neck pain. The research by Nejati et al. [16] reported significant differences between the neck pain and healthy control groups regarding the HTA in working position and not in neutral forward-looking position. Further, a substantial correlation between thoracic posture and neck pain was documented. However, in another study, Tsunoda et al. [14] did not discern a substantial association between increased kyphosis and neck-shoulder pain. In a study on computer workers by Szeto et al. [15], no significant differences were observed in the assumed sagittal postures of the thoracic spine while performing a keyboard task between the case and the control groups.

A cohort study by Poussa et al. [17] reported that thoracic kyphosis was not a significant risk factor for the development of neck pain. A cohort of school children (in the age group of 10–13 years) was assessed annually for thoracic kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, height, and weight until the age of 22 years. During the last visit, history and the presence of neck pain were evaluated. However, no significant association between thoracic kyphosis and neck pain was seen in the adolescent age group.

Two studies reported the relationship between thoracic spine mobility and neck pain. The work by Falla et al. [18] investigated the amount of trunk rotation during a walking task in neck pain individuals and healthy, pain-free controls. It was concluded that the participants with neck pain had reduced trunk rotations compared to asymptomatic controls during any speed of walking. The number was further reduced in the neck pain group when neck rotations were added. In another study by Kaya and Çelenay [19], thoracic mobility was established to have a negative correlation with neck pain intensity, and a decrease in the mobility by more than 30° was found to be a critical factor for neck pain.

The relationship between forward head posture (FHP), that is, a smaller CVA and thoracic kyphosis (measured with HTA/UTA) was investigated in three studies. Lau et al. [4] testified to the presence of smaller CVA and greater UTA in participants with neck pain in comparison with the control group devoid of neck pain. Further, a significant negative correlation was present between thoracic kyphosis and CVA in the study by Quek et al. [13]. The authors suggested that an increase in thoracic kyphosis was correlated with lower CVA, that is, increased FHP. Moreover, a multiple mediation analysis revealed that increased FHP along with thoracic kyphosis caused mobility limitations in the cervical spine. In another study by Yu et al. [20], a multiple linear regression was described, in which the cervical angles were correlated with thoracic kyphosis and T1 slope angle in cervical spondylitis individuals.

The present literature review was performed to examine the presence of thoracic spine dysfunction in the neck pain population. The review identified nine studies fulfilling the specified inclusion criteria and investigated the impact of thoracic posture and mobility on chronic neck pain.

Increased kyphosis was determined by the presence of greater upper/HTA. UTA is measured as an angle between horizontal and a line drawn between the seventh cervical and thoracic spinous processes [13]. Among the five studies exploring the relationship of thoracic posture with neck pain intensity, two reported significant positive correlations and two more demonstrated contradictory results with no correlation between the two variables [4,14,15]. Besides, one study concluded that neck pain was positively associated with hyperkyphosis during a functional typing task [16]. Further, Lau et al. [4] reported that the UTA was better related to the presence of neck pain than the CVA.

The severity of pain is determined by a variety of other physical and psychosocial contributing factors [21]. Hence, these contradictory results might be due to multiple factors, such as psychological features influencing the neck pain severity and chronicity [21]. Thus, thoracic malalignment (that is, increased kyphosis) may be one among the multiple contributors to neck pain. Only one prospective study reported thoracic kyphosis as not a significant contributing factor [17]. But the work involved adolescent population in whom the incidence of neck pain may be too low to reveal a difference between individuals with and without thoracic kyphosis. However, the other studies lacked a prospective design and could not adequately investigate thoracic spine posture as a contributing risk factor for neck pain.

Impaired cervical mobility is one of the significant features of neck pain. Studies on normal individuals noted that cervical movement is dependent on thoracic posture and mobility [4]. Nevertheless, only a few studies have investigated the impairment of thoracic mobility in neck pain individuals. Norlander et al. [7,22] as well as Norlander and Nordgren [23] in 1998 reported that reduced segmental mobility in the upper thoracic spine could predict the onset of neck and shoulder pain. The researchers argued that thoracic manipulation could restore cervicothoracic junction mobility and hence alleviate cervical dysfunction.

Another study reported that neck pain patients exhibited reduced trunk rotations while walking [18]. The reduction in trunk movement was claimed to be a generalized protective response of the pain centers to avoid further injury. It appears from the discussion of these authors that reduced trunk rotation is a consequence of neck pain. However, walking with reduced trunk movement places excessive mechanical stress on the lumbar spine, leading to low-back pain [18].

The only study that measured thoracic mobility in the sagittal plane observed a significant difference between the neck pain and healthy control groups. However, the causative mechanisms for reduced thoracic mobility are underreported and poorly studied [19]. Thoracic mobility decreases with age, and therefore, it is still unclear whether these restrictions are independent of the aging-related stiffness of the thoracic spine [13].

Among the various relationships described in the present review, increase in thoracic kyphosis and FHP were consistently correlated across the three studies [4,13,16]. This connection suggests that increased kyphosis is a crucial factor in the development of FHP and hence neck pain. A greater FHP has been ascertained to be associated with reduced cervical ranges and thus contribute to neck pain. FHP increases the compressive loading on the cervical spine structures [13]. This plausible association is supported by Quek et al. [13], who demonstrated that FHP is a mediator between thoracic kyphosis and neck pain. Furthermore, a randomized control trial by Lau et al. [24] uncovered that manipulation of the thoracic spine improved FHP and cervical flexion range of motion, which further substantiates the above findings.

The cervical spine and the head complex are positioned and balanced on the kyphotic curve of the thoracic spine. A change in the thoracic alignment might therefore cause compensatory changes in the cervical curve to preserve the normal forward gaze [20]. Increased thoracic kyphosis leads to the anterior shift of the trunk mass through an alteration of the thoracic spine loading, thereby resulting in FHP of the cervical spine as compensation [4]. The FHP increases the compressive loading of the cervical spine and places abnormal stress on its posterior noncontractile elements [4]. Flexion of the thoracic spine was shown to increase the cervical spine erector spinae electromyography activity, which further accentuates the stress on the posterior spinal structures in the neck [4]. The results of the review also reported the presence of FHP with thoracic hyperkyphosis. Sustained FHP due to the above reasons is implicated in the alteration of cervical motor control and the development of myofascial dysfunction, thereby contributing to neck pain.

In a rigid thoracic spine (as occurring with hyperkyphosis), increased loads are placed on the postural muscles spanning the neck and the upper back, which considerably impair motor control [14]. In certain demanding postures that challenge the equilibrium, patients tend to further limit the motion of the spine, which results in reduced trunk rotations while walking. The increase in stiffness is not energetically efficient and hence increases the muscle co-contraction, thereby further enhancing the compressive load on the cervical spine [18].

In persons involved in computer-related work, persistent improper posture has been reported. Plausible reasons can be a lack of awareness regarding the body position during work; high concentration or focus, which may increase stress as a maladaptive coping strategy; and impaired motor control [16]. Altered/increased thoracic kyphosis causes mobility impairments at C7–T1 and T1–T2 levels [4]. Reduced mobility in the lower cervical segments can be compensated by increased movement at the upper cervical levels [13]. This occurrence could lead to impaired control and irritation of the nociceptive structures in the spine and hence, the onset of neck pain. Nonetheless, the effect could also be the result of ‘reverse causation,’ as hyper thoracic kyphosis could not be conclusively established as a causative factor in neck pain development.

Most of the articles considered in the review reported the presence of thoracic dysfunction in the neck pain population. Two features, namely impaired thoracic mobility and relationship between FHP and thoracic kyphosis, were evident. Therefore, the review reinforces the inclusion of thoracic spine evaluation and treatment in the management of neck pain. Furthermore, the findings provide the conceptual basis for studies that investigate the effectiveness of thoracic spine mobilization procedures [24], as they can restore the normal biomechanics of the thoracic spine and lower the mechanical stress in the cervical spine [25,26]. However, a few studies also reported the absence of relationship between cervical pain and thoracic kyphosis. Nevertheless, a cutoff value for thoracic mobility (more than 30°) associated with neck pain has been identified in one study. Clinicians need to consider the results of these studies while assessing and treating neck pain.

The review has a few limitations. A variety of study methods and outcome measures were identified across the studies, and hence, a meta-analysis could not be performed. As only one prospective trial was determined, the cause-effect relationship between thoracic posture and neck pain could not be examined.

The current evidence suggests that the thoracic spine is possibly a contributing factor for neck pain. However, the studies identified in this topic are limited. Additionally, the number of studies that investigated the contributions of thoracic spine alignment and mobility as risk factors for the presence of neck pain is minimal. Thus, further research with a prospective study design might be helpful in establishing whether impaired thoracic dysfunction is a risk factor for the development of neck pain. Mobilization/manipulation of the thoracic spine is often performed with the aim of improving thoracic mobility; however, only minimal studies have examined the relationship between the two variables. Therefore, further research must identify the prevalence of thoracic mobility restrictions in the neck population and assess their impact on the severity and prognosis of the ailment. Besides, it is also unclear whether thoracic dysfunction is a predisposing or contributing factor for neck pain, thus necessitating further research on the cause and effect relationship.

A significant relationship is present between thoracic kyphosis and postural alteration of the cervical spine. However, thoracic kyphosis has not been uniformly correlated with neck pain intensity, which could be due to the multiple causative factors that are responsible for pain in general. Thus, the review favors the inclusion of thoracic spine assessment and treatment in managing mechanical neck pain. Owing to a lack of prospective trials in the area, thoracic kyphosis cannot be established as a risk factor for neck pain development. Further research is strongly recommended to investigate the cause-effect relationship between thoracic posture and cervical dysfunction.

Fig. 2.

Measures of sagittal posture of cervical and thoracic spine. Angle A: upper thoracic angle. Angle B: craniovertebral angle.

Table 1.

Description of the included studies

| No. | Study | Study design | Participants | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poussa et al. [17] (2004) | Cohort study | 1,060 4th grade school children (age, 10–13 years) in Finland, were assessed annually till the age of 21.9 years. | 1. Body weight & height, trunk asymmetry in degrees, TK, and LL were assessed every year. | 1. Cumulative lifetime neck pain incidence was 58% in males and 78% in females. |

| With drop-outs over time total 430 children assessed | 2. At the last examination, a questionnaire was given for history of neck pain. | 2. Amongst people having neck pain, majority recalled <8 days with pain. Only one-fifth experienced >30 days of pain. | |||

| 3. Presence of neck pain. Its overall duration in the previous year, location and incidence of neck pain in the last year was determined. | 3. A predictor for the incidence of neck pain was short stature at the age of 11 years. | ||||

| 4. Neck pain predictors were analyzed with a logistic regression model. | 4. An inverse association between neck pain history and current body height was found at 22-year age (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.45–0.86). | ||||

| 5. Male sex was protective against neck pain (OR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.18–0.44). | |||||

| 6. No other anthropometric measures were found to be predictors of neck pain. | |||||

| 2 | Szeto et al. [15] (2005) | Case-control study | Female office workers assigned into case (n=23) and control (n=20) groups. All subjects were experienced, touch-typists. | 1. Upper body postures and movements during a 1-hour typing task were recorded using the Vicon 370 ver. 3.1 (Oxford Metrics, Oxford, UK), 3D motion measurement, and analysis system. | 1. Case subjects had a mean head flexion 3.9º more than controls. This greater head–neck flexion in cases was maintained over the whole 1-hour typing task. |

| Subjects with current and past complaints of discomfort in neck and shoulder within the past 7 days and with discomforts lasting >3 months in the previous year were assigned to the case group. | 2. Six infra-red cameras were used to record the video at a sampling frequency of 60 Hz. | 2. Significant between-group differences present for flexion range, side flexion median, and rotation median postures. | |||

| A significant difference in their mean age of about 5 years was present. Twenty-one subjects in the case group still had a similar mean age (35.8±4.6 years). | 3. Reflective markers were placed over the head–neck segment, thorax segment, and shoulder segment. | 3. Cases and controls had thoracic postures and movements generally within 1º of each other, and a multivariate analysis of variance found no signifi- cant effect of group (nor time). | |||

| Subjects were comparable regarding their physical build, their work backgrounds, and their computer experience. | 4. The subject was instructed to adjust the screen height, key- board height, and chair height until a reasonably comfortable and erect posture was attained. | 4. Cases had about 1º more right shoulder flexion and 3º less right shoulder abduction. | |||

| 5. A standardized typing package was given for the common 1-hour typing task. | 5. Significant correlation found between head flexion and side flexion angles and right UT activity (rho=0.366, p=0.024; rho=0.336, p=0.039). | ||||

| 6. Synchronized kinematics and electromyography signals were captured at the 5th, 20th, 35th, 50th, and 60th minutes of the typing task. Each data capture was for a 60-second duration. | 6. Significant correlation seen between right shoulder abduction angle and right UT activity (rho=0.348, p=0.032). | ||||

| 7. Subjects rated the task related discomfort in 10 upper body regions (left/right neck, upper back, shoulder, elbow, and wrist/hand) on a scale of 0–10 immediately after each capture. | |||||

| 3 | Lau et al. [4] (2010) | Cross-sectional correlation study | Subjects in the age group 20 to 50 years | 1. Subjects filled in the Chinese version of the NPQ and NPRS. | 1. The neck pain group showed a significantly higher UTA than the non-neck pain group. |

| The control group consisted of subjects who had no neck pain in the last 6 months, scor- ing zero on the NPRS and <10% on the NPQ | 2. Cervical and thoracic spine postures were measured from a lateral photograph. | 2. The CVA of the neck pain group was significantly smaller than the controls. | |||

| Participants in the neck pain group were diag- nosed by physicians. Their pain intensity was >3 on the NPRS, and they had a score >10% on the NPQ. | 3. Thoracic spine sagittal posture (UTA) was measured as an angle between the horizontal line and a line drawn between the seventh cervical spinous process and the seventh thoracic spinous process. | 3. Positive correlation was present between UTA and presence of neck pain (rho=0.63; 95% CI, 0.45–0.76; p<0.01). | |||

| Gender and age were comparable between both groups. | 4. Cervical spine sagittal posture was measured as an angle be- tween a line drawn from the tragus of the ear to the seventh cervical vertebra subtended to the horizontal, i.e., the CVA. | 4. Negative correlation between the CVA and pres- ence of neck pain (rho=0.56; 95% CI, 0.71–0.36; p<0.01) | |||

| 5. Two sessions were arranged to measure the above. | 5. A greater UTA and a smaller CVA were likely to be found in the subjects with neck pain. | ||||

| 6. After the adjustment of age and gender, the UTA (OR, 1.37; p<0.01) and the CVA (OR, 0.86; p=0.04) were significant predictors for the presence of neck pain. | |||||

| 7. UTA was not a significant predictor for neck pain intensity on NPRS (p=0.31) and NPQ (p=0.16). | |||||

| 4 | Quek et al. [13] (2013) | Cross-sectional | 51 Older adults having cervical dysfunction | 1. Disability was measured using the NDI. | 1. Older age was associated with the reduction in cervical ROM (Spearman r=0.41 and r=0.51 for general and upper cervical rotation, respectively). |

| Age (yr): 66±4.9 (range, 60–78) | 2. The flexicurve method was used to measure TK. The flexicurve was aligned according to C7, and S2 spinous processes and the flexicurve’s shape was aligned to the spinal curvature. Next, the flexicurve was placed on a table, and a picture of the flexicurve imprint was taken using a 7.2 megapixels digital camera (Sony DSC-W110). | 2. The relationships between cervical ROM and CVA (lesser CVA indicates greater FHP) revealed positive associations between CVA and general cervical rotation (r=0.33, p=0.02), cervical flexion (r=0.30, p=0.03), and upper cervical rotation (r=0.15, p=0.31). | |||

| Female=29, male=22 | |||||

| Height (m): 1.61±0.1 (range, 1.45–1.89) | |||||

| Mass (kg): 61±14.5 (range, 41–130) | 3. FHP was assessed from a digitized, lateral-view photograph of the subject in his/her usual standing posture. Once the photograph was obtained, ImageJ was used to measure FHP, quantified by the CVA (i.e., the angle between the horizontal line passing through C7 and a line extending from the tragus of the ear to C7). Lesser CVA indicates greater FHP. | 3. Significant negative association was found between TK and CVA (r=0.48, p<0.001). | |||

| BMI (kg/m2): 23.4±3.8 (range, 17.1–36.4) | 4. TK was shown to be associated with FHP. | ||||

| Presently on pain medication (number): 7 | |||||

| Cervical pain intensity on VAS (/10): 2.0±1.7 (range, 0–6) | 4. Neck ROM was measured using the cervical ROM device. The following measurements were taken: (1) total active cervical flexion range in an upright sitting, (2) total active cervical rota- tion ROM in an upright sitting, and (3) passive upper cervical rotation in available full flexion in supine. | 5. FHP affected general cervical rotation and cervical flexion (but not upper cervical rotation). | |||

| TK index: 10.6±2.3 (range, 5.1–16.4) | |||||

| CVA (°): 45.6±6.7 (range, 31–59) | |||||

| NDI (/100) 18.0±12.5 (range, 0–44) | |||||

| 5 | Tsunoda et al. [14] (2013) | Case-control study | 329 Japanese subjects in a Japanese village | 1. Participants were asked to report the occurrence of NSP in the last 2 weeks. Participants answering “yes” were categorized into NSP group. | 1. Mean ages of subjects in both groups were significantly different (p<0.001). |

| Prevalence of NSP (%): 52.0 | 2. Sagittal spinal alignment was evaluated using Spinal Mouse—an electronic, non-invasive computer-aided device. | 2. Significantly number of females complained of NSP than males (p<0.01). | |||

| Age (yr): 65.5±10.7 | 3.The subject was asked to assume an upright position. Spinal Mouse was moved paravertebrally from C7 to S3. | 3. There was no significant association between TK angle and NSP (NSP group: 40.6°±10.8°, non-NSP group: 40°±11°). | |||

| Gender (male/female): 125/204 | 4. TK angle, LL angle, and inclination of the line from T1 to S1 relative to a perpendicular line were calculated. | 4. Mean LL and mean inclination were significantly higher in NSP group. | |||

| 6 | Nejati et al. [16] (2015) | Case-control study | The entire population of the full time was working employees of the Iran University of Medical Science (job included office work with a desktop computer; total=159 employees). | 1. Posture was assessed for each participant, in the office at the employee’s desks between the 4th and 5th hours of work by one investigator. | 1. Statistically significant differences between the symptomatic and asymptomatic groups, in CVA and HTA, were found only during work (CVA, p=0.04; HTA, p=0.02). |

| Employees with chronic pain, soreness or ache experienced in a region between the inferior margin of the occipital bone and T1 for a period of >3 months were included in the symptomatic group, while all the other employees were assigned to the control group. | 2. Adhesive markers were attached to the spinous process of C7, T7, and tragus. | 2. In the looking forward task/neutral position, no significant differences found between groups (CVA, p=0.70; HTA, p=0.43). | |||

| Mean age (yr): 39±8 | 3. The participants were made to type a standard text on their computers for about 5 minutes, and then researcher took a picture during last minutes of typing. | 3. The employees with neck pain showed a poor posture of cervical and thoracic spine at work. | |||

| Work duration (yr): 14±8 | 4. A 2nd picture was taken where the researcher asked the participants to sit on their chairs and look forward ahead at a fixed point on the wall, 120 cm above the ground. | 4. Correlations were also found between the sagittal posture of the cervical and thoracic spine (CVA, HTA) and neck pain. | |||

| Weight, height, and BMI also comparable in both groups | 5. Body Posture Analyzer software was used to assess photographic data. | ||||

| 73% were females | 6. HTA and CVA were measured. | ||||

| 7 | Yu et al. [20] (2015) | Case-control study | A group of 120 asymptomatic subjects (including 63 males and 57 females; average age 23.2±6.3 years old) | 1. All preoperative full-length and lateral cervical X-rays of the spine were taken. Patients stood in a comfortable erect position with their hands on supports. A commercially available optical scanner (XR 650; GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to digitize the films. | 1. Significant differences observed between the cervical alignments of different Roussouly types in both cohorts. |

| A cohort of 121 cervical spondylitis cases (involving 80 men and 41 women; average age 53.3±10.6 years old) were recruited. | 2. Angles and distances were calculated using a custom computer application (PACS; GE Electrics, Boston, MA, USA) | 2. No correlation between cervical alignment and the value of PI in both asymptomatic and spondylotic groups (p >0.05) | |||

| All cervical spondylotic cases were operated (anterior cervical discectomy/corporectomy with bone fusion or posterior laminoplasty). | 3. Global radiological parameters measured PI, SS, PT, spinalsacral angles, the ratio of hip to C7/hip to the sacrum, C0–C2 angle, T1 slope angle, LL, and TK. | 3. There were significant differences in T1 slope and TK between lordotic and kyphotic alignments (29.6°±6.2° vs. 20.6°±6.4°, p=0.00; 28.0°±8.4° vs. 19.7°±6.5°, p=0.00), and between straight and | |||

| 4. The cervical sagittal alignment was categorized into four types: lordosis, straight, sigmoid, and kyphosis. | kyphotic alignments (26.3°±6.3° vs 20.6°±6.3°, p=0.01; 27.2°±6.1° vs. 19.7°±6.5°, p=0.00) in asymptomatic cohort. | ||||

| 5. The degenerative changes of disc space narrowing, endplate sclerosis, osteophyte formation was recorded for each cervical disc space. | 4. In spondylotic patients, significant differences were found in T1 slope and TK between lordotic and straight cervical alignments (27.2°±7.8° vs. 22.4°±7.4°, p=0.04; 35.9°±10.1° vs. 29.7°±8.5°, p=0.01). | ||||

| 6. All subjects in both cohorts were categorized with Roussouly Morphological Classification according to their PI, SS, PT, thoracic, and lumbar alignments. | 5. Multiple linear regression of all parameters showed that cervical angles were significantly related to the C0–C2, TK, and T1 slope (p=0.00, 0.01, and 0.00, respectively). | ||||

| 8 | Falla et al. [18] (2017) | Case-control design | People with chronic nonspecific neck pain, between 18 and 40 years | 1. A questionnaire on subject demographics and history, duration, and average intensity and localization of pain were administered. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, the NDI, Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia, and Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health Survey were also completed. | 1. The average speed during the self-selected speed condition was not associated with group or condition. |

| 14 Cases & 14 controls | 2. No interactions between group, speed, and condition for stride cadence. | ||||

| Cases-episodic, non-specific neck pain of >3 months in duration, with periods of aggravation and remission in the past 6 months, each episode of neck pain lasting at least a week, and having sufficiently intense pain to limit function. | 2. All subjects were made to walk on a treadmill at any selfselected speed and 3 km/hr and 5 km/hr with three different head orientations (head neutral, 30° of right rotation, and 30° of left rotation), i.e., a total of nine gait tasks. | 3. No significant interactions present between factors for stride length. | |||

| Mean age (yr): 28±6.9 | 3. For precise tracking of head movement and orientations, subjects wore a custom-made helmet (weight, 280 g) equipped with three reflective spherical markers (diameter, 18 mm), and two presentation laser pointers mounted parallel to the subject’s view. | 4. For the neck rotation angles, no significant interactions observed. For trunk rotation, no interactions were observed; but there was a significant main effect for speed (F=83.19, p<0.001), with greater rotation during gait at 5 km/hr compared to both the self-selected speed and 3 km/hr (both: post hoc, p<0.001). | |||

| 78% females | |||||

| Height (cm): 173.3±10.1 | 4. The sequence of trials was randomized. | 5. Compared to the symptomatic group, controls displayed greater trunk rotations (post hoc, p<0.001), regardless of the speed or condition. | |||

| Weight (kg): 67.4±9.5 | 5. For each condition, the subject walked 120 seconds. The subjects were allowed 30 seconds to adjust to the condition, and data acquisition started after 30 seconds and lasted for 90 seconds. | 6. Trunk rotation reduced even further in the patient group when the head was rotated compared to the extent of trunk movement seen in the neutral head condition. | |||

| Pain duration (mo): 72±44.5 | 6. A motion-analysis system tracked 3D positions of the reflective markers with eight infrared digital video cameras capturing at 128 samples per second. | 7. No significant differences were observed for trunk rotation variability, between groups and conditions. | |||

| NDI score: 36.1±14.1 | 7. Heel strike, stride length, strike cadence, neck & trunk rotations, and their variability were calculated. | ||||

| No significant differences were observed between groups for age, weight, or height. | |||||

| 9 | Kaya and Çelenay [19] (2017) | Case-control | 132 Patients (age, 18–60 years) complaining of neck pain for >3 months | 1. Demographic data and physical characteristics collected. BMI was calculated. | 1. A higher sagittal curvature in the thoracic spine (p<0.001) and a lower sagittal thoracic mobility (p=0.013) was seen in neck pain group as compared to controls. |

| 56 Chronic neck pain group | 2. The intensity of neck pain was assessed using the VAS | 2. Neck pain intensity and thoracic curvature showed positive correlation (r=0.391, p<0.001). | |||

| 53 Control group. Controls included BMImatched healthy individuals with no previous neck pain. | 3. Sagittal thoracic posture and mobility were evaluated by Spinal Mouse, in the standing position. | 3. But thoracic mobility and neck pain intensity were negatively correlated (r=-0.260, p=0.006). | |||

| 4. Thoracic curvature was assessed in upright, maximum flexion, and maximum extension positions. | 4. Thoracic kyphotic curvature more than 45° is critical for chronic neck pain. | ||||

| 5. The sagittal curvature and mobility between T1 and T2 was calculated with a software program. | 5. Similarly, the decrease in thoracic mobility >30° is critical for chronic neck pain. |

TK, thoracic kyphosis; LL, lumbar lordosis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; 3D, three-dimensional; UT, upper trapezius; NPRS, Numeric Pain Rating Scale; NPQ, Northwick Park Neck Pain Questionnaire; UTA, upper thoracic angle; CVA, craniovertebral angle; BMI, body mass index; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; NDI, Neck Disability Index; FHP, forward head posture; ROM, range of motion; NSP, neck shoulder pain; HTA, high thoracic angle; PI, pelvic incidence; SS, sacral slope; PT, pelvic tilt.

References

2. Blanpied PR, Gross AR, Elliott JM, et al. Neck pain: revision 2017. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017 47:A1–83.

3. Takasaki H, May S. Mechanical diagnosis and therapy has similar effects on pain and disability as ‘wait and see’ and other approaches in people with neck pain: a systematic review. J Physiother 2014 60:78–84.

4. Lau KT, Cheung KY, Chan KB, Chan MH, Lo KY, Chiu TT. Relationships between sagittal postures of thoracic and cervical spine, presence of neck pain, neck pain severity and disability. Man Ther 2010 15:457–62.

5. Peterson DH, Bergman TF. Chiropractic technique: principles and procedures. 2nd ed. Louis (MO): Mosby; 2002.

6. Deepa A, Dabholkar TY, Yardi S. Comparison of the efficacy of Maitland thoracic mobilization and deep neck flexor endurance training versus only deep neck flexor endurance training in patients with mechanical neck pain. Indian J Physiother Occup Ther 2014 8:77–82.

7. Norlander S, Gustavsson BA, Lindell J, Nordgren B. Reduced mobility in the cervico-thoracic motion segment: a risk factor for musculoskeletal neck-shoulder pain: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Scand J Rehabil Med 1997 29:167–74.

8. Oxland TR. Fundamental biomechanics of the spine: what we have learned in the past 25 years and future directions. J Biomech 2016 49:817–32.

9. Cleland J, Selleck B, Stowell T, et al. Short-term effects of thoracic manipulation on lower trapezius muscle strength. J Man Manip Ther 2004 12:82–90.

10. Jull GA, O’Leary SP, Falla DL. Clinical assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles: the craniocervical flexion test. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2008 31:525–33.

11. Young JL, Walker D, Snyder S, Daly K. Thoracic manipulation versus mobilization in patients with mechanical neck pain: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther 2014 22:141–53.

12. Cross KM, Kuenze C, Grindstaff TL, Hertel J. Thoracic spine thrust manipulation improves pain, range of motion, and self-reported function in patients with mechanical neck pain: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011 41:633–42.

13. Quek J, Pua YH, Clark RA, Bryant AL. Effects of thoracic kyphosis and forward head posture on cervical range of motion in older adults. Man Ther 2013 18:65–71.

14. Tsunoda D, Iizuka Y, Iizuka H, et al. Associations between neck and shoulder pain (called katakori in Japanese) and sagittal spinal alignment parameters among the general population. J Orthop Sci 2013 18:216–9.

15. Szeto GP, Straker LM, O’Sullivan PB. A comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic office workers performing monotonous keyboard work: 2. neck and shoulder kinematics. Man Ther 2005 10:281–91.

16. Nejati P, Lotfian S, Moezy A, Nejati M. The study of correlation between forward head posture and neck pain in Iranian office workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2015 28:295–303.

17. Poussa MS, Heliovaara MM, Seitsamo JT, Kononen MH, Hurmerinta KA, Nissinen MJ. Predictors of neck pain: a cohort study of children followed up from the age of 11 to 22 years. Eur Spine J 2005 14:1033–6.

18. Falla D, Gizzi L, Parsa H, Dieterich A, Petzke F. People with chronic neck pain walk with a stiffer spine. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2017 47:268–77.

19. Kaya DO, Celenay ST. An investigation of sagittal thoracic spinal curvature and mobility in subjects with and without chronic neck pain: cut-off points and pain relationship. Turk J Med Sci 2017 47:891–6.

20. Yu M, Zhao WK, Li M, et al. Analysis of cervical and global spine alignment under Roussouly sagittal classification in Chinese cervical spondylotic patients and asymptomatic subjects. Eur Spine J 2015 24:1265–73.

21. Smart KM, Blake C, Staines A, Doody C. Clinical indicators of ‘nociceptive’, ‘peripheral neuropathic’ and ‘central’ mechanisms of musculoskeletal pain: a Delphi survey of expert clinicians. Man Ther 2010 15:80–7.

22. Norlander S, Aste-Norlander U, Nordgren B, Sahlstedt B. Mobility in the cervico-thoracic motion segment: an indicative factor of musculo-skeletal neckshoulder pain. Scand J Rehabil Med 1996 28:183–92.

23. Norlander S, Nordgren B. Clinical symptoms related to musculoskeletal neck-shoulder pain and mobility in the cervico-thoracic spine. Scand J Rehabil Med 1998 30:243–51.

24. Lau HM, Wing Chiu TT, Lam TH. The effectiveness of thoracic manipulation on patients with chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized controlled trial. Man Ther 2011 16:141–7.