Palliative Posterior Instrumentation versus Corpectomy with Cage Reconstruction Treatment for Thoracolumbar Pathological Fracture

Article information

Abstract

Study Design

Single-center, retrospective cohort study.

Purpose

We aimed to evaluate and compare the clinical outcomes in patients who underwent palliative posterior instrumentation (PPI) versus those who underwent corpectomy with cage reconstruction (CCR) for thoracolumbar pathological fracture.

Overview of Literature

The requirement for anterior support after corpectomy has been emphasized in the treatment of pathological fractures of the vertebrae. However, for patients with a relatively short life expectancy, anterior reconstruction may not be required and posterior instrumentation alone may provide adequate stabilization.

Methods

A total of 43 patients with metastases of the thoracolumbar spine underwent surgery in the department of orthopaedic and traumatology of Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine from 2003 to 2016. Surgical outcomes were assessed on the basis of survival status, pre- and postoperative pain, complication rate, and operation time.

Results

PPI was performed for 22 patients and CCR was performed for 21 patients. In the PPI group, the follow-up period of the five surviving patients was 32 months. The remaining 17 patients died with a mean survival duration of 12.3 months postoperatively. In the CCR group, the five surviving patients were followed up for an average of 14.1 months. The remaining 16 patients died with a mean survival duration of 18.7 months postoperatively. No statistically significant difference (p=0.812) was noted in the survival duration. The Visual Analog Scale scores of the patients were significantly reduced after both procedures, with no significant difference noted on the basis of the type of surgical intervention (p>0.05). The complication rate in the CCR group (33.3%) was higher compared with that in the PPI group (22.7%); however, this difference was not noted to be statistically significant (p=0.379). The average operation time in the PPI group (149 minutes) was significantly shorter (p=0.04) than that in the CCR group (192 minutes).

Conclusions

The PPI technique can decompress the tumor for functional improvement and can stabilize the spinal structure to provide pain relief.

Introduction

Spinal metastases most frequently affect the vertebral bodies of the spinal column and can result in the destruction of the vertebral body, causing spinal cord compression or spinal instability [1]. Deterioration in the neurological functional features and pain are the most common complaints in these patients. The treatment goals in the management of patients with the metastatic spinal disease include pain alleviation, preservation of the neurological function, and maintenance or restoration of spinal stability [1,2]. Pain relief and preservation of neurological function are possible via partial or total excision of the lesion anteriorly or posteriorly with adequate surgical decompression [3-5]. Several studies have demonstrated that anterior column reconstruction is necessary following tumor excision [6,7]. However, Chen et al. [8] found that the thoracic spine has a stable construct, which eliminates the need for anterior reconstruction. Anterior reconstruction may be redundant owing to the association with severe morbidity, and it is contraindicated in patients with a poor general condition. Palliative posterior instrumentation (PPI) is a promising option, particularly in patients with short life expectancy, for providing adequate stability and better pain relief.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate and compare the clinical outcomes in patients with thoracolumbar pathological fracture who underwent PPI versus those who underwent corpectomy with cage reconstruction (CCR).

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective study by evaluating the records of patients who underwent surgery in the department of orthopaedic and traumatology of Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine from 2003 to 2016 for pathologic fractures of the thoracic or the lumbar vertebrae. Institutional review board approval was obtained from the Istanbul University Faculty of Medicine before study initiation (IRB approval no., 2018/1305). The patients’ medical histories and radiographic images were assessed regarding medical registration files. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age >18 years, (2) availability of demographic data and medical record, and (3) thoracic or lumbar vertebral pathological fracture. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) traumatic fracture and (2) cervical fracture.

Surgical intervention was provided to patients with an estimated life expectancy of >6 weeks and to those with progressive neurologic deficits, spinal instability, and intolerable pain resistant to conservative treatment. We evaluated the age, sex, primary cancer, preoperative and postoperative Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain score, postoperative survival rate, duration of hospitalization, operation time, blood transfusion, postoperative complications, metastases to visceral organs, preoperative and postoperative neurologic status use of Frankel grade and grouped as non-ambulatory or ambulatory and also calculated. The Tokuhashi scoring system that preoperatively evaluates patient prognosis in cases of metastatic spinal tumor was also evaluated and used for comparing the two groups.

1. Surgical procedures

1) Palliative posterior instrumentation

A single midline incision was made for adequate tumor exposure in patients in the prone position. Total laminectomy was performed one level above and below the affected segment. Facetectomies and pedicle resection of the affected vertebra were performed. The goals of the surgery included adequate decompression and palliative tumor excision. Lastly, instrumentation was performed with pedicle screws above and below the lesion until the stable construct was achieved (Fig. 1).

A 55-year-old patient with breast cancer. (A, B) Anteroposterior radiograph and sagittal magnetic resonance image showing the collapse of the T–12 vertebra because of metastatic breast cancer. (C, D) Anteroposterior and lateral radiograph obtained 3 months after the palliative posterior instrumentation, showing no loss of fixation.

2) Corpectomy with cage reconstruction

A single midline incision was made for adequate tumor exposure in patients in the prone position. This procedure comprised en-bloc laminectomy and total or subtotal corpectomy followed by anterior instrumentation with cage and posterior spinal instrumentation. Posterior fixation was performed at 2 or 3 levels above and below the resected vertebra. A titanium mesh cage or expandable cage with autogenous bone graft was used for anterior column reconstruction (Fig. 2).

3) Follow-up

All the patients were reviewed at the outpatient clinic at 1, 6, and 12 weeks, as well as at 6 months, and once a year thereafter till they died. All patients were operated upon by two senior surgeons (T.A. and C.S.); T.A. preferred the palliative procedure, while C.S. preferred corpectomy and cage reconstruction.

2. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS ver. 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used for evaluating the survival of patients who died. Paired t-test was used for assessing the variation in the VAS pain score and Frankel neurological status. Independent t-test was employed for comparing the age, follow-up, complication rate, duration of hospitalization, operation time, and blood transfusion. Fisher’s exact test was used for analyzing the improvement in the neurological function and the complication rates between the two groups.

Results

A total of 43 patients were enrolled in the present study. The median age at the time of surgery was 53.3 years (range, 37–84 years); 22 patients were men and 21 were women. In 33 cases, the thoracic vertebra was affected, and in 10, the lumbar vertebra was affected. Lung cancer was the most frequently occurring type of primary cancer, with nine patients having been diagnosed with lung cancer. The demographic data have been distributed as per treatment group in Tables 1 and 2.

Demographic data of the patients who underwent PPI or CCR metastases of the thoracolumbar spine fracture

PPI was performed in 22 cases, while CCR was performed in 21 cases. The mean age of the patients who underwent PPI was 56.6 years and of those who underwent CCR was 51.0 years; the difference between the mean ages of the two groups was not noted to be statistically significant (p=0.341). The operation time for PPI ranged from 90 to 240 minutes (mean, 149±18 minutes), while that for CCR ranged from 120 to 420 minutes (mean, 192±29 minutes); the operation times for the two procedures were noted to be significantly different (p=0.04). Blood transfusion was in the CCR group was 2.3 (range, 0–6) and in PPI group was 2.1 (range, 0–5). No significant difference was noted between the two groups (p=0.724). The hospitalization time in the PPI group was 4–80 days (mean, 11.2±16.2 days), while that in the CCR group was 3–36 days (mean, 11.9±8.1 days); no significant difference was noted (p=0.992).

In the PPI group, the follow-up period of the five surviving patients ranged from 12 to 78 months (average, 32±12.6 months). The remaining 17 patients died with a mean survival duration of 12.3±3.1 months (range, 10 days to 46 months) following the surgery. In the CCR group, the follow-up period for the five surviving patients ranged from 12 to 18 months (average, 14.1±1.7 months). The remaining 16 patients died with a mean survival duration of 18.7±9.1 months (range, 2–137 months) after the surgery. The average follow-up duration for the PPI group was 16.9±18.9 months (range, 10 days to 78 months) and that for the CCR group was 17.5±23.1 months (range, 2–137 months). No statistically significant difference was noted between the follow-up duration in the two groups (p=0.812).

The Kaplan–Meier curve showed that two patients in the PPI group died in the first month following PPI; an average 90.4%±0.6% of the patients survived for more than 1 month, eight died within 6 months, 63.6%±10.2% survived for >6 months, 11 died in the first year, 44.6%±10.7% survived for >1 year, 14 died in the second year, 26.7%±10.4% survived for >2 years. Following CCR, no patient died during the first month, eight died within 6 months, 60%±11% survived for >6 months, 11 died in the first year, 45.6%±11.1% survived for >1 year, 13 died in the second year, and 22.5%±12.4% survived for >2 years (Fig. 3). Log-rank test findings showed no statistically significant difference in the survival between the two groups (p=0.844).

The Kaplan-Meier curve showing the postoperative survival status in the two groups. PPI, palliative posterior instrumentation; CCR, corpectomy with cage reconstruction.

Back pain was present in all 43 patients prior to the surgery. The VAS score improved in all patients. In patients who underwent PPI, the mean preoperative VAS score was 7.9 (range, 6–9) and the postoperative VAS score was 2.9 (range, 1–5) in the first month. Improvement in the VAS score was noted to be statistically significant (p<0.001). In patients with CCR, the mean preoperative VAS score was 8.1 (range, 5–9) and the postoperative VAS score was 2.5 (range, 2–5). The improvement in the VAS score was noted to be statistically significant (p<0.001). However, no significant difference was observed in the VAS score between the two procedures (p=0.73).

The complication rate in the CCR group (33.3%) was higher than that in the PPI group (22.7%); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p=0.379). There were seven recorded cases of perioperative complications in the CCR group, including urinary tract infection, postoperative pneumonia (n=2), and superficial wound problems and infections (n=3). No patients underwent revision surgery and implant failure was not observed in any patient.

Five cases of complications were recorded in the PPI group. One patient experienced implant failure and wound problems 2 months postoperatively. There was no problem after the revision surgery for 29 months until death. One patient had fatigue kyphosis under single-level instrumentation. However, the patient did not undergo revision surgery because of poor medical condition. The other three patients had urinary tract and gastrointestinal system tract infection.

Two patients in the PPI group exhibited improved postoperative status. One of them who was preoperatively Frankel A became Frankel C; the other who was preoperatively Frankel D became Frankel E postoperatively. A total of 16 patients were ambulatory at the time of the surgical intervention; of these, 15 were in grade E, and one was in grade D in the PPI group. However, there was no postoperative change in the ambulation ratios.

Four patients with CCR group showed improved postoperative status. Two of the four preoperative Frankel C patients became ambulatory. Fourteen patients were ambulatory at the time of the surgical intervention; of these, 11 were in Frankel grade E, and three were in grade D in the CCR group. After surgical intervention, 16 patients were ambulatory; of these, 12 were in Frankel grade E and four patients were in grade D.

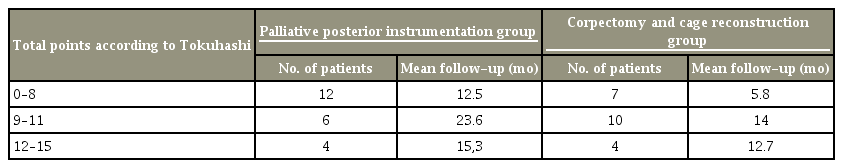

The scores among the two groups according to the Tokuhashi scale including the number of patients for each group and the medium length of survival in months for the groups is presented in Table 3.

Discussion

Adequate decompression and stabilization are the treatment goals of pathological vertebral fracture surgery. In this study, we found that PPI surgery provides sufficient decompression and pain relief in comparison with the CCR procedure. Anterior reconstruction has been recommended by several authors [6,9]. However, the complication rates of this procedure are high. The new cage, called the expandable, also involves a high complication rate. In the study by Akeyson and McCutcheon [10], the complication rate was noted to be 48%, and majority of these complications were associated with anterior reconstruction. Chen et al. [8] conducted a multicenter prospective study wherein 21 patients underwent anterior column reconstruction completed with an expandable cage. In the present study, the complication rate was 14.3%. Viswanathan et al. [11] reported that 95 patients underwent implantation with an expandable titanium cage. In this study, the complication rate was 16%, and any cases of implant loosening or failure were noted using follow-up radiography (mean follow-up, 9.52±8.37 months); three patients survived for >2 years without implant failure or loosening.

Anterior vertebral reconstruction also enhances blood loss and operation time and may lead to increase morbidity and complications. These factors increase the noteworthy concerns for patients with metastatic tumors and poor general condition because they may result in delayed treatment with chemotherapy/target therapy or radiotherapy. Thus, PPI with laminectomy is more valuable than other methods.

Studies have reported the outcomes of surgery without anterior reconstruction. In a large series, Walter et al. [12] studied 57 consecutive patients with metastatic vertebral tumors who were treated with posterolateral transpedicular approach without anterior reconstruction. No implant failure was reported. The complication rate was only 5.3%, including one seroma and two superficial wound infection cases [12]. Another study reported a high complication rate, wherein Cho and Sung [13] studied 21 consecutive patients with metastatic tumors who were treated using the posterolateral transpedicular approach without anterior reconstruction and reported a complication rate of 19 % (four of 21). Bridwell et al. [14] analyzed 25 patients with metastatic spine disease treated with the posterolateral transpedicular approach and posterior segmental spinal instrumentation and reported no case of implant failure. In this study, the complication rate was 22.7% for the palliative group, and only one patient had implant loosening and failure as recorded with follow-up radiography (mean follow-up period, 16.9±18.9 months), and seven patients survived for >2 years without implant failure or loosening.

Various studies have reported that the quality of life (QOL) in patients with spinal metastases improves after surgical treatment [15,16]. The Frankel classification and the VAS were used for measuring the QOL in patients with spinal metastases [15,17]. In their study, Ibrahim et al. [17] evaluated patients using the Frankel scale and found that 71% of the entire group had better pain control, 53% regained or maintained their independent mobility, and 39% regained urinary sphincter function. In the present study, all patients showed an improved VAS score and six patients showed improved Frankel status.

Our study has certain limitations. First, this was a retrospective study. Second, the sample size was relatively small. Third, the duration of the follow-up period was comparatively short.

Conclusions

The goals of the palliative operation in managing metastatic spine tumor with fewer postoperative complications, patients can accept further oncologic therapies (including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy) promptly and may have a better functional status and quality of life. Posterior instrumentation alone appears to be a more appropriate choice for these patients.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Serkan Bayram: drafted the paper; Turgut Akgül: critical revision of the paper; Murat Altan: analysis and interpretation of data; Tuna Pehlivanoğlu: acquisition of data; Özcan Kaya: critical revision of the paper; Mustafa Abdullah Özdemir: acquisition of data; and Necdet Sağlam: critical revision of the paper.