|

|

- Search

| Asian Spine J > Volume 13(4); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effect of percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic surgery (PTES) for lateral recess stenosis (LRS)(LRS) in elderly patients and to assess patientsŌĆÖ health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Overview of Literature

PTES is an increasingly used surgical approach, primarily employed for lumbar disc herniation treatment. However, indications for PTES have been increasing in recent years. PTES has been recommended as a beneficial alternative to open decompression surgery in specific LRS cases; PTES is termed as percutaneous endoscopic ventral facetectomy (PEVF) in such cases.

Methods

In total, 65 elderly patients with LRS were prospectively studied. Patients presented severe comorbidities (coronary insufficiency, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and respiratory failure); thus, general anesthesia administration would potentially cause considerable hazards. All the patients underwent successful PEVF in 2015ŌĆō2016. The patients were assessed preoperatively and at 6 weeks; 3, 6, and 12 months; and 2 years postoperatively. PatientsŌĆÖ objective assessment was conducted according to specific clinical scales; the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was separately used for leg and low-back pain (VAS-LP and VAS-BP, respectively), whereas the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire was used for the HRQoL evaluation.

Results

All studied parameters presented maximal improvement at 6 weeks postoperatively, with less enhancement at 3 and 6 months with subsequent stabilization. Statistical significance was found in all follow-up intervals for all parameters (p<0.05). Parameters with maximal absolute amelioration were VAS-LP, bodily pain, and role limitations due to physical health problems. In contrast, VAS-BP, general health, and mental health were comparatively less enhanced.

Lumbar spinal stenosistenosis (LSS) is a remarkably freqequent spinal ailment in the elderly, constituting the most common indication for spine surgery in this patient subpopulation [1,2]. The prevalence of LSS gradually increases with age and is estimated to be 66.6% in the age range 60ŌĆō69 years [3]. Anatomically, LSS is classified into two distinct sub types: central stenosis (CS) and lateral stenosis [2]. Lateral stenosis can be further subclassified into lateral recess stenosis (LRS) and foraminal stenosis [4]. The proportional reduction in the diameter of the lumbar spinal canal is associated with the compression of neurovascular structures and the appearance of clinical symptomatology [5]. When surgical treatment is indicated, decompression surgery with or without fusion is typically performed [6].

Percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy (PTED) is a novel, full-endoscopic surgical technique, primarily used for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation (LDH) [7]. PTED is becoming increasingly popular in the field of spine surgery owing to its surgical advantages [8]. PTED is associated with the preservation of dorsal musculature and spine elements, lesser intraoperative hemorrhage, low perioperative morbidity rates, and rapid rehabilitation [8-11].

The minimally invasive character and surgical advantages of PTED has broadened the spectrum of indications in recent years. Thus, percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic surgery (PTES) has been recently proposed for surgical management of LRS. In such cases, the technique is termed as percutaneous endoscopic ventral facetectomy (PEVF) [6]. Although it is a recent development, PTES utilization for LRS treatment has gained considerable interest in literature [6,12-17]. However, none of these studies have reported specific results about health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in elderly patients with LRS after PTES. Furthermore, none of these studies focused only on the elderly, including a relatively satisfactory sample.

The aim of this study was to study particular outcomes of postoperative HRQoL, focusing on elderly patients after PTES using the transforaminal endoscopic surgical system (TESSYS) technique.

Our study enrolled only elderly patients aged >65 years (World Health Organization definition of elderly/older person) [18]. All the patients had LRS and were theoretically appropriate for open decompression surgery, meeting all current indications. All the patients were completely informed about the studyŌĆÖs aims and scope, and all the patients provided written informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Interbalkan European Medical Center (Thessaloniki, Greece) and local ethics committee. All aspects of this study were conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, outlined in the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised 2013).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) radiculopathy; (2) neurogenic claudication; (3) sensory or motor neurological deficit; (4) LRS, particularly due to excessive osseous growth rather than yellow ligament hypertrophy/ossification, as confirmed by radiological examination of the lumbar spine (Figs. 1ŌĆō3), in compliance with clinical find ings; (5) failure of 12-weeksŌĆÖ conservative treatment; and (6) elderly patients with a contraindication for general anesthesia due to severe comorbidities, such as coronary insufficiency, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, and respiratory failure.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) noncontaminated disc hernia exceeding one-third of the spinal canal on sagittal magnetic resonance imaging scans; (2) sequestration of the disc; (3) recurrent herniated disc or previous surgery at the affected level; (4) segmental instability or spondylolisthesis; (5) vertebral fracture; or (6) spinal tumor or infection.

A prospective study with 65 patients was designed and conducted. Patient age, presence of comorbidities, and imaging findings (emergence of LRS, particularly as a result of excessive osseous growth rather than yellow ligament hypertrophy/ossification) raised the dilemma of the selection of a surgical treatment method. After careful review of the medical history, clinical and radiological examination, and consultation between the surgeon, the anesthesiologist, and the radiologist, PTES was selected. All patients thus underwent successful PEVF for LRS in 2015ŌĆō2016 and were subsequently assessed at regular follow-up intervals: at 6 weeks; 3, 6, and 12 months; and at 2 years postoperatively. Preoperative values were also acquired. Objective evaluation of the patientŌĆÖs health was performed using specific clinical scales. The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used for lower-limb and low-back pain (VAS for limb pain [VAS-LP] and VAS for back pain [VAS-BP]). Moreover, HRQoL was evaluated using the Short Form 36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36).

All the patients underwent full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy by the same spine surgeon with experience in PTED with TESSYS. Local anesthesia and mild sedation were used for the surgical procedure. Patients were preoperatively placed in the lateral decubitus position, lying down on the opposite side. Optimal foraminal space enlargement was thus accomplished. Disinfection of the surgical field as well as a local anesthetic injection at the point of needle entrance were subsequently performed. Initial introduction of the needle was done at 11 cm lateral to the midline. Transit corridor was thus leading in KambinŌĆÖs triangle (safe zone) [19]. The rational needle position during gradual promotion was continuously validated intraoperatively by fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 4). Sequential passage of reamers was then performed along with mild sedation and analgesia (fentanyl ampule) administration. The diameters of the reamers were 5.5, 6.5, and 7.5 mm (Joimax System; Joimax, Irvine, CA, USA), thus accomplishing satisfactory foraminoplasty (Fig. 5). The cannula and endoscope were subsequently advanced, accomplishing lateral recess decompression with ventral facetectomy (Fig. 6).

VAS implementation is a convenient and illustrative process for the assessment of various parameters, including pain [20]. A unipolar horizontal line (100 mm) was used in our study. Patients were asked to indicate with a mark the level of pain experienced by them. Separate VASs were used for lower-limb and low-back pain, obtained at every follow-up interval evaluation. Every score was calculated in millimeters to one decimal place. The minimal clinically remarkable alteration was determined to be 9 mm, whereas other parameters, such as sex, age, and pain etiology were not independently analyzed [21].

SF-36 represents a widely used method for HRQoL assessment in spine surgery [22,23]. It comprises 36 distinct items, assessing eight parameters regarding the general health and daily life of patients: physical function (PF); role limitations due to physical health problems (RP); bodily pain (BP); general health (GH); energy, fatigue and vitality (V); social functioning (SF); role limitations due to emotional problems (RE); and mental health (MH). Each patient was asked to respond to the structured questionnaire at each follow-up interval. Overall results were then collected and processed, and were converted to a percentage. A higher score is related to favorable HRQoL in all studied parameters. If responses were provided for less than half the entries, the questionnaires were considered invalid.

Statistical analysis of the data was conducted using IBM SPSS software ver. 23.00 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The categorical variables were expressed as percentages, and the continuous variables (age, VAS scores, and SF-36 scores) were expressed as mean┬▒standard deviation. Comparisons of the continuous parameters were accomplished using the Student t-test and Wilcoxon test, when a normal distribution was present and absent, respectively. The level of statistical significance was set at p=0.05. The VAS scores and SF-36 scores were preoperatively assessed and at all regular follow-up intervals.

All the patients successfully completed all follow-up sections. The majority of patients exhibited no perioperative complications and were discharged on the first postoperative day. Two patients (3.1%) presented postoperative dysesthesia in exiting nerve root distribution (L5ŌĆōS1 in both cases), which was completely improved by the first examination at 6 weeks.

The patientsŌĆÖ demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All the parameters were evaluated preoperatively and at 6 weeks; 3, 6, and 12 months; and 2 years postoperatively. The data are presented in Table 2.

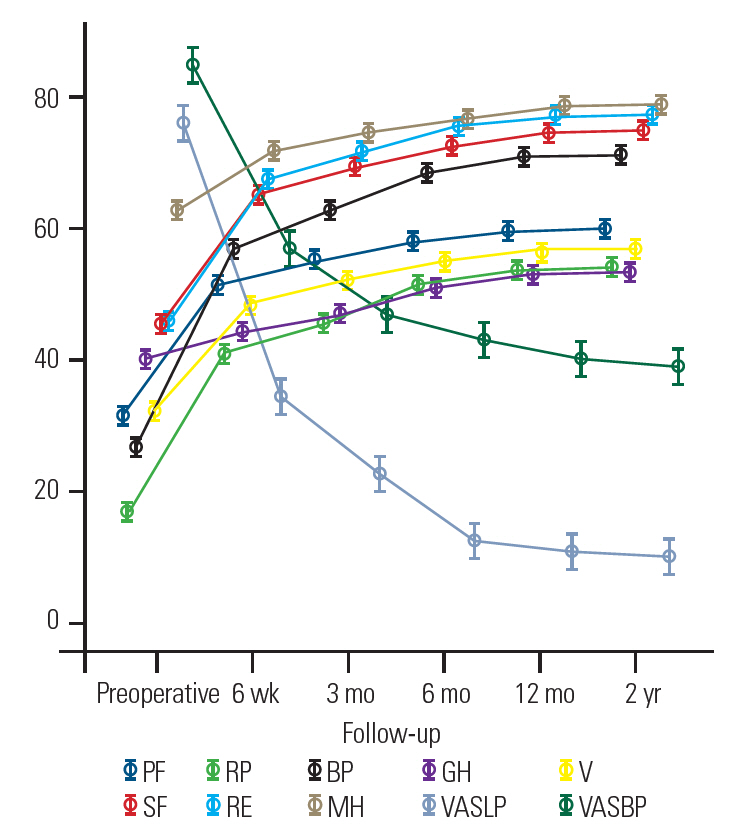

All parameters showed maximum improvement at 6 weeks postoperatively, following a similar alteration pattern. Additional amelioration occurred until 3 and 6 months postoperatively, with subsequent stabilization and only minimal improvement (Table 2, Fig. 7). Statistical significance was observed for all values at all follow-up intervals (Table 2).

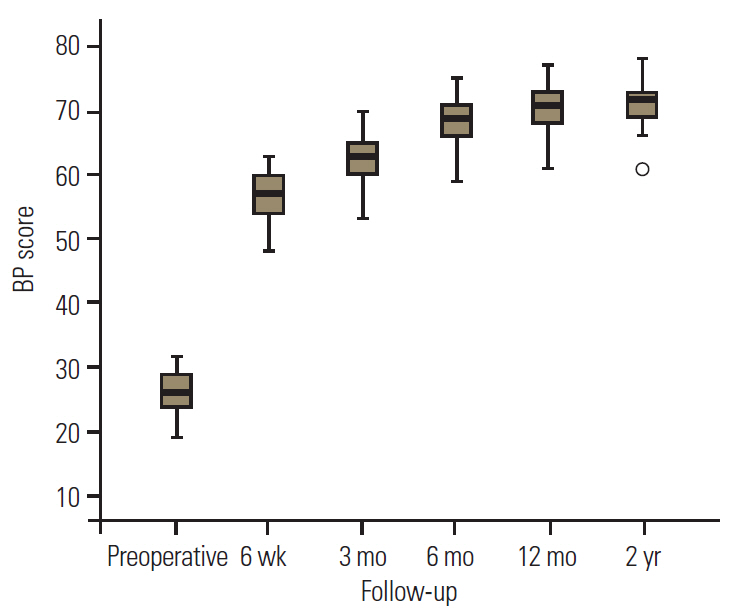

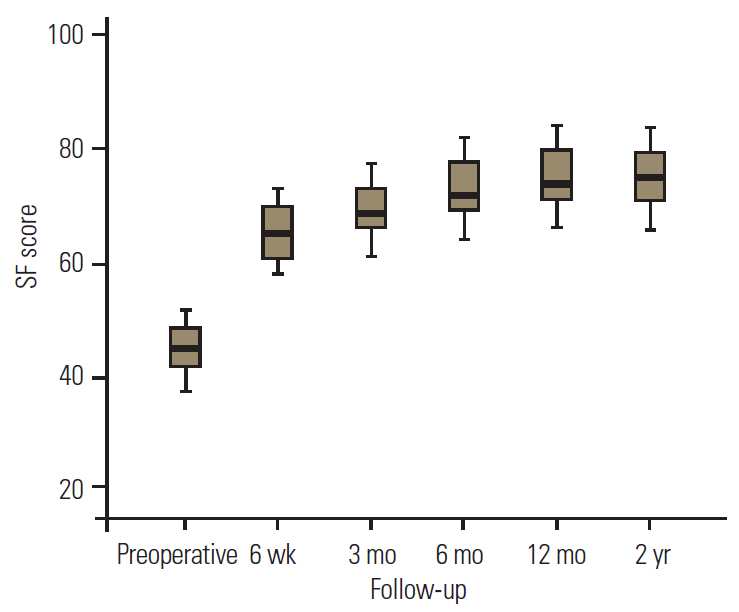

Comparative assessment of SF-36 parameters revealed that BP and RP were the most improved (Table 2, Figs. 7, 8). In contrast, relatively moderate improvements were observed in PF, V, SF, and RE (Table 2, Figs. 7, 9), whereas MH and GH presented comparatively minimal amelioration (Table 2, Figs. 7, 10).

Regarding VAS scores, improvement patterns were similar for the lower-limb and low-back pain assessments. Nevertheless, absolute reduction in VAS scores was greatest for the VAS-LP (Table 2, Fig. 7). In contrast, amelioration of VAS-BP during various follow-ups was slight to moderate. Patients continued to express considerable back pain at the end of follow-up (Table 2, Fig. 7).

LSS is a common clinical condition that significantly contributes to pain and disability, particularly in the elderly [3]. Reductions in spinal canal diameters and subsequent compression of neurovascular structures can be caused by single or multiple etiologies. Anterior disc protrusions (soft or calcified) and arthritic hypertrophy or posterior ossification/calcification of facet joints, yellow ligaments, or lamina can all lead to spinal canal limitation and subsequent compression [24]. Patients commonly express neurogenic claudication and/or radicular symptomatology, sometimes with chronic low-back pain [5,24]. A clinical differential diagnosis of CS from lateral stenosis might be impossible owing to the similarity of clinical manifestations. However, the severity of neuropathic pain is greater in lateral stenosis owing to the involvement of spinal nerves and dorsal root ganglia [2].

PTED is an innovative, full-endoscopic, minimally invasive, surgical technique for spine [7]. Despite the surgical advantages, this technique can be associated with considerable risks for the beginner spine surgeon as well as for the patient [25]. However, rational and experienced conduction of PTED is related to minimal surgical trauma, minimization of epidural space scarring, shorter hospitalizations and rehabilitation times, and low perioperative morbidity and pain. Furthermore, it is conducted under local anesthesia and mild sedation, requiring only a small incision of 8 mm, rather than general anesthesia [6-11,25].

Recently, PTES has been recommended for the treatment of LRS instead of the gold standard open decompression surgery [15]. Lateral recess decompression is accomplished with ventral facetectomy (PEVF) [6]. PTES has also been proposed for the treatment of failed back surgery syndrome with a background of recurrent or residual LDH and lateral stenosis [13].

Lewandrowski [12] conducted the first thorough evaluation of the role of PTES in various types of LSS. He retrospectively studied 220 patients with lateral stenosis with or without LDH, conducting percutaneous transforaminal decompression using the outside-in technique. Although decompression in the middle and exit foraminal zones was adequate, entry zone decompression was found to be inadequate with this technique and was associated with clinical failure [12].

These results were different from those of subsequent studies. Li et al. [14] performed a prospective study to determine the outcomes of PTES in LRS with or without the presence of LDH. A total of 85 patients (mean age, 56.7 years) underwent percutaneous lumbar foraminoplasty and decompression, using a specially designed instrument for LRS. A 2-year follow-up was performed. Postoperative assessment demonstrated that VAS (for low-back and leg pain) and Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) values were remarkably enhanced at each follow-up. In addition, PTES outcomes for the majority of patients were favorable according to the MacNab scores evaluation. Based on these data, it was concluded that PTES with foraminoplasty and decompression constitutes a beneficial alternative in LRS surgical treatment in terms of safety and effectiveness [14].

More recently, broad easy immediate surgery (BEIS) was tested in concordance with percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic technology for LRS in elderly patients. A total of 21 patients were prospectively studied with a 1-year follow-up. Postoperatively, VAS and ODI scores were found to be significantly improved. In addition, implementation of modified MacNab criteria revealed that 14 patients had ŌĆśexcellentŌĆÖ results, five ŌĆśgood,ŌĆÖ and two ŌĆśfair.ŌĆÖ It was therefore suggested that percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic BEIS could be efficiently used to treat LRS in the elderly [16].

Chen et al. [17] also currently reported specific outcomes of PTES in elderly patients with LRS. A total of 25 patients (mean age, 79.6 years) were enrolled and postoperatively evaluated for a mean interval of 23ŌĆō34 months (reporting though specific results until 1 year postoperatively). VAS scores for lower-limb pain, ODI scores, and MacNab criteria were implemented for the clinical assessment. VAS scores as well as ODI scores were demonstrated to be significantly improved at all follow-ups in comparison with preoperative values. A clinical course of 21 patients (87.5%) was defined as ŌĆśexcellentŌĆÖ or ŌĆśgoodŌĆÖ 12 months postoperatively, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of PTES for LRS surgical management in geriatric patients [17].

The results of these studies are consistent with our data [14,16,17]. The statistical analysis in our study revealed that VAS-LP and VAS-BP were significantly improved at all times in the follow-up. However, the VAS-LP absolute alteration was remarkably greater than that of VAS-BP, which, despite statistical significance, presented slight to moderate improvement. This difference might be attributed to the age of our patients. All the patients were elderly, presenting severe degenerative alterations in radiological evaluation. These alterations (and particularly an excessive abnormal bone development as described) resulted in LRS. PEVF was performed at only one level, targeting nerve root and dorsal ganglia decompression. Therefore, absolute amelioration of leg pain indicated satisfactory lateral recess decompression, whereas the considerable remaining back pain could be attributed to general degenerative lumbar spine disease in these patients.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to include an HRQoL evaluation in elderly patients after full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy with the TESSYS technique for LRS. We believe that pain constitutes only one parameter of HRQoL and is insufficient to express the universal outcome of PTES in patientsŌĆÖ postoperative daily life. Based on these hypotheses, we assessed overall HRQoL, thus performing a more multifactorial evaluation of our patients and excluding safer results about the techniqueŌĆÖs actual effects.

Our results demonstrated that all parameters of SF-36 were significantly improved at all follow-up intervals. Amelioration was demonstrated to be quantitatively maximal in 6 weeksŌĆÖ time postoperatively, with further improvements at 3 and 6 months in all parameters. However, the chronic interval of 3 months constituted a determinant of patientsŌĆÖ subsequent clinical course. Values of all indexes presented their maximal postoperative climax, whereas overall alterations after 3 months and until the end of follow-up were not quantitatively remarkable.

Nevertheless, differences were also observed here; the parameters with maximal improvement were BP and RP, whereas MH and GH showed minimal improvements. Based on these results, we hypothesize that leg pain due to neurovascular structure compression in LRS represents a serious part of patientsŌĆÖ general subjective perception of pain. Therefore, amelioration of leg pain (and in lower grade of back pain) results in significant enhancement of the BP parameter. In contrast, MH and GH parameters were minimally improved, possibly owing to the impaired mental state and the presence of comorbidities in these patients.

Regarding postoperative complications, two of our patients (3.1%) had provisional dysesthesia in exiting nerve root distribution. Both patients underwent PTES at the L5ŌĆōS1 level, and dysesthesia was completely conservatively regressed at the 6-week postoperative assessment. This complication has also been reported by other authors in their studies. Li et al. [14] had reported the emergence of postoperative exiting nerve root dysesthesia in three patients (3.5%), all surgically treated at the L5ŌĆōS1 level. Moreover, Zhang et al. [16] reported the presence of lower-limb paresthesia in one patient (4.8%), being conservatively treated at 3 months postoperatively. Chen et al. [17] also reported this complication in one patient (4%), with successful conservative treatment after 2 weeks. From our point of view, postoperative dysesthesia at the L5ŌĆōS1 level can emerge as an outcome of intraoperative root irritation due to the level particularity. The presence of anatomic obstacles such as iliac wings and the extent of L5 transverse processes considerably contribute to the narrowing of the intervertebral foramen, thereby complicating surgical access via the transforaminal approach [10]. However, the temporary nature of this entity limits its surgical significance.

Limitations of our study include the relatively small sample size as well as the relatively limited follow-up evaluation. Nevertheless, there are no large prospective clinical studies in the current literature regarding transforaminal full-endoscopic surgery in elderly patients with LRS with a follow-up of >1 year. Moreover, all patients recruited in our study were characterized by the synchronous presence of considerable comorbidities. Additional studies with larger samples, more extensive follow-up evaluations (e.g., assessing mid-term results in 2ŌĆō5 years postoperatively), and enrollment of otherwise healthy elderly individuals (in potential comparative studies of PTES versus conventional open decompression surgery) should be conducted to further elucidate and verify the outcomes of full-endoscopic ventral facetectomy in LRS surgical treatment in elderly patients.

PTES was associated with postoperative improvements in leg and low-back pain, in conjunction with statistically significant amelioration in all parameters of HRQoL. Improvements in all values were maintained until the end of the 2-year follow-up.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the current literature to use SF-36 for HRQoL evaluation in elderly patients after PTES for LRS. PTES was associated with notably less postoperative pain and remarkably improved quality of life. All studied indexes featured maximal amelioration at 6 weeks postoperatively, with subsequent lesser improvement at 3 and 6 months and further stabilization. VAS-LP, BP, and RP were demonstrated to present maximal comparative amelioration, whereas VAS-BP, GH, and MH were less ameliorated. PEVF was therefore demonstrated to be a satisfactory alternative in terms of safety and effectiveness in elderly patients, whose severe comorbidities often automatically exclude the possibility of general anesthesia and open decompression surgery.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Kapetanakis is a reference doctor for Joimax GmbH and receives payments for teaching. No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Notes

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Kapetanakis S; data acquisition : Gkantsinikoudis N, Thomaidis T; analysis of data: Charitoudis G; drafting of the manuscript : Gkantsinikoudis N; critical revision : Kapetanakis S, Theodosiadis P; obtaining funding: Kapetanakis S; administrative support: Thomaidis T, Theodosiadis P; and supervision : Kapetanakis S, Theodosiadis P.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Preoperative computed tomography of an enrolled patient, demonstrating the presence of lateral recess stenosis due to excessive osseous growth.

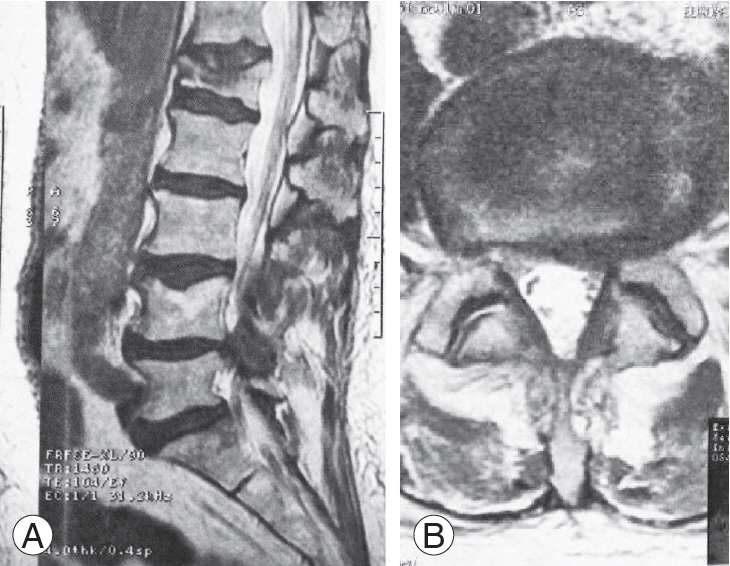

Fig.┬Ā2.

Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging, indicating the significant compression of nerve roots in right lateral recess due to inordinate osseous development.

Fig.┬Ā3.

Preoperative (A) left para-sagittal and (B) axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating lateral recess stenosis primarily due to excessive abnormal osseous development and disc degeneration.

Fig.┬Ā7.

Schematic representation of all index alteration during follow-up intervals. PF, physical function; RP, role-physical; BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; V, energy, fatigue and vitality; SF, social function; RE, role-emotional; MH, mental health; VAS-LP, Visual Analog Scale for leg pain; VAS-BP, Visual Analog Scale for back pain.

Table┬Ā1.

Patients demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Population size | 65 |

| Age (yr) | 72.3┬▒4.2 |

| Sex | |

| ŌĆāMale | 30 (46.2) |

| ŌĆāFemale | 35 (53.8) |

| Operated level | |

| ŌĆāL3-L4 | 3 (4.6) |

| ŌĆāL4-L5 | 42 (64.6) |

| ŌĆāL5-S1 | 20 (30.8) |

Table┬Ā2.

Parameters evaluation during the various follow-up intervals

| Parameter | Preoperative Mean┬▒SD |

6 wk |

3 mo |

6 mo |

12 mo |

2 yr |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean┬▒SD | p-valuea),b) | Mean┬▒SD | p-valuea),b) | Mean┬▒SD | p-valuea),b) | Mean┬▒SD | p-valuea),b) | Mean┬▒SD | p-valuea),b) | ||

| Physical function | 31.0┬▒2.8 | 51.2┬▒2.9 | <0.001 | 54.9┬▒3.0 | <0.001 | 57.7┬▒3.1 | <0.001 | 59.4┬▒3.1 | <0.001 | 59.7┬▒3.2 | <0.001 |

| Role-physical | 16.2┬▒3.9 | 41.2┬▒4.0 | <0.001 | 45.3┬▒4.1 | <0.001 | 51.3┬▒4.1 | <0.001 | 53.7┬▒4.1 | <0.001 | 54.0┬▒4.1 | <0.001 |

| Bodily pain | 26.6┬▒3.3 | 56.6┬▒3.3 | <0.001 | 62.6┬▒3.2 | <0.001 | 68.6┬▒3.2 | <0.001 | 70.9┬▒3.3 | <0.001 | 71.1┬▒3.2 | 0.001 |

| General health | 39.7┬▒1.9 | 44.1┬▒2.0 | <0.001 | 46.7┬▒2.2 | <0.001 | 51.0┬▒2.5 | <0.001 | 53.2┬▒2.4 | <0.001 | 53.5┬▒2.5 | <0.001 |

| Energy, fatigue and vitality | 31.5┬▒2.9 | 47.7┬▒3.1 | <0.001 | 52.0┬▒3.0 | <0.001 | 55.0┬▒3.1 | <0.001 | 56.4┬▒3.2 | <0.001 | 56.6┬▒3.2 | <0.001 |

| Social function | 45.0┬▒4.2 | 65.2┬▒4.3 | <0.001 | 69.3┬▒4.4 | <0.001 | 72.5┬▒4.4 | <0.001 | 74.7┬▒4.4 | <0.001 | 74.9┬▒4.5 | <0.001 |

| Role-emotional | 45.4┬▒4.3 | 67.6┬▒4.3 | <0.001 | 71.6┬▒4.4 | <0.001 | 75.7┬▒4.3 | <0.001 | 77.1┬▒4.4 | 0.001 | 77.3┬▒4.4 | 0.001 |

| Mental health | 62.7┬▒3.3 | 71.7┬▒3.2 | <0.001 | 74.6┬▒3.1 | <0.001 | 76.6┬▒3.0 | <0.001 | 78.6┬▒3.1 | <0.001 | 78.8┬▒3.1 | <0.001 |

| VAS for leg pain (mm) | 76.2┬▒11.3 | 34.0┬▒8.4 | <0.001 | 22.2┬▒7.6 | <0.001 | 11.7┬▒6.5 | <0.001 | 10.6┬▒6.3 | 0.008 | 9.5┬▒6.2 | 0.008 |

| VAS for back pain (mm) | 84.5┬▒10.3 | 57.1┬▒11.0 | <0.001 | 46.6┬▒9.6 | <0.001 | 42.6┬▒7.8 | <0.001 | 39.9┬▒7.8 | <0.001 | 38.6┬▒7.7 | 0.005 |

References

1. Marawar SV, Madom IA, Palumbo M, et al. Surgeon reliability for the assessment of lumbar spinal stenosis on MRI: the impact of surgeon experience. Int J Spine Surg 2017 11:34.

2. Lin JH, Hsieh YC, Chen YC, Wang Y, Chen CC, Chiang YH. Diagnostic accuracy of standardised qualitative sensory test in the detection of lumbar lateral stenosis involving the L5 nerve root. Sci Rep 2017 7:10598.

3. Kalichman L, Cole R, Kim DH, et al. Spinal stenosis prevalence and association with symptoms: the Framingham Study. Spine J 2009 9:545ŌĆō50.

4. Ahn Y. Percutaneous endoscopic decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis. Expert Rev Med Devices 2014 11:605ŌĆō16.

5. Doualla-Bija M, Takang MA, Mankaa E, Moutchia J, Ongolo-Zogo P, Luma-Namme H. Characteristics and determinants of clinical symptoms in radiographic lumbar spinal stenosis in a tertiary health care centre in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017 18:494.

6. Sairyo K, Chikawa T, Nagamachi A. State-of-the-art transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic lumbar surgery under local anesthesia: discectomy, foraminoplasty, and ventral facetectomy. J Orthop Sci 2018 23:229ŌĆō36.

7. Kapetanakis S, Gkantsinikoudis N, Chaniotakis C, Charitoudis G, Givissis P. Percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy for the treatment of lumbar disc herniation in obese patients: health-related quality of life assessment in a 2-year follow-up. World Neurosurg 2018 113:e638ŌĆō49.

8. Kapetanakis S, Giovannopoulou E, Charitoudis G, Kazakos K. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy for lumbar disc herniation in ParkinsonŌĆÖs disease: a case-control study. Asian Spine J 2016 10:671ŌĆō7.

9. Kapetanakis S, Giovannopoulou E, Thomaidis T, Charitoudis G, Pavlidis P, Kazakos K. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy in Parkinson disease: preliminary results and short review of the literature. Korean J Spine 2016 13:144ŌĆō50.

10. Kapetanakis S, Charitoudis G, Thomaidis T, Theodosiadis P, Papathanasiou J, Giatroudakis K. Health-related quality of life after transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy: an analysis according to the level of operation. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 2017 8:44ŌĆō9.

11. Kapetanakis S, Gkasdaris G, Thomaidis T, Charitoudis G, Kazakos K. Comparison of quality of life between men and women who underwent transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy for lumbar disc herniation. Int J Spine Surg 2017 11:28.

12. Lewandrowski KU. ŌĆ£Outside-inŌĆØ technique, clinical results, and indications with transforaminal lumbar endoscopic surgery: a retrospective study on 220 patients on applied radiographic classification of foraminal spinal stenosis. Int J Spine Surg 2014 8.

13. Yeung A, Gore S. Endoscopic foraminal decompression for failed back surgery syndrome under local anesthesia. Int J Spine Surg 2014 8.

14. Li ZZ, Hou SX, Shang WL, Cao Z, Zhao HL. Percutaneous lumbar foraminoplasty and percutaneous endoscopic lumbar decompression for lateral recess stenosis through transforaminal approach: technique notes and 2 years follow-up. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2016 143:90ŌĆō4.

15. Sairyo K, Higashino K, Yamashita K, et al. A new concept of transforaminal ventral facetectomy including simultaneous decompression of foraminal and lateral recess stenosis: technical considerations in a fresh cadaver model and a literature review. J Med Invest 2017 64:1ŌĆō6.

16. Zhang SM, Wu GN, Jin J, et al. Application of broad easy immediate surgery in percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic technology for lumbar lateral recess stenosis in the elderly. Zhongguo Gu Shang 2018 31:317ŌĆō21.

17. Chen X, Qin R, Hao J, et al. Percutaneous endoscopic decompression via transforaminal approach for lumbar lateral recess stenosis in geriatric patients. Int Orthop 2018 Jul 19 [Epub]. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-018-4051-3

19. Kambin P, Brager MD. Percutaneous posterolateral discectomy: anatomy and mechanism. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987 (223): 145ŌĆō54.

20. Wewers ME, Lowe NK. A critical review of visual analogue scales in the measurement of clinical phenomena. Res Nurs Health 1990 13:227ŌĆō36.

21. Kelly AM. Does the clinically significant difference in visual analog scale pain scores vary with gender, age, or cause of pain? Acad Emerg Med 1998 5:1086ŌĆō90.

22. Bombardier C. Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine 2000 25:3100ŌĆō3.

23. Zanoli G, Jonsson B, Stromqvist B. SF-36 scores in degenerative lumbar spine disorders: analysis of prospective data from 451 patients. Acta Orthop 2006 77:298ŌĆō306.