Postoperative Clinical Outcomes of Balloon Kyphoplasty Treatment: Would Adherence to Indications and Contraindications Prevent Complications?

Article information

Abstract

Study Design

We retrospectively assessed the postoperative clinical outcomes of balloon kyphoplasty (BKP).

Purpose

To evaluate the risk factors for complications and to reconfirm the indications and contraindications for BKP.

Overview of Literature

In Japan, BKP is indicated for cases of osteoporotic vertebral fractures when pain is not improved even after an adequate period of conservative treatment. Contraindications to BKP include pedicle fracture, fracture of a flat vertebra, or fracture of the posterior wall of the vertebral body diagnosed on computed tomography.

Methods

Seventy-five patients who underwent BKP in our institution participated in this study; 49 provided follow-up data. Those with complications and persistent pain were assigned to the “eventful” group; the others, to the “uneventful” group. We evaluated risk factors for complications and persistent pain, including the presence or absence of severe posterior wall injury/pedicle fracture, the shape of the vertebral body, and the time period from onset of pain to BKP.

Results

The incidences of severe posterior wall injury, pedicle fracture, and flattened vertebral body did not differ significantly between the uneventful and eventful groups. However, there was a significant difference in disease duration between those with and those without adjacent vertebral fractures (AVFs): The incidence of AVF was lower among patients with disease of less than 8 weeks’ duration.

Conclusions

Disease duration is a possible risk factor for developing AVF, whereas other characteristics were not risk factors for complications after BKP. Although it has been suggested that BKP treatment in the early phase after injury results in a good outcome, the indications should be determined according to prognosis that is based on findings obtained with tools such as imaging examinations.

Introduction

Balloon kyphoplasty (BKP) is a useful surgical procedure for the repair of osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVFs) because it reduces pain in patients with osteoporosis during the early postoperative period [1-9]. Several reports have shown that rates of mortality and overall morbidity were lower among patients with OVFs who underwent BKP than among those who received conservative treatment [10-12]; therefore, the pain relief provided by BKP in the early postoperative period probably affects patients’ overall status positively [10,11]. However, complications can occur after surgery; in particular, adjacent vertebral fractures (AVFs) frequently occur when the vertebral bodies adjacent to the one treated by BKP subsequently fracture, and this is a major clinical problem (Fig. 1) [13-18].

Plain radiograph after balloon kyphoplasty, showing a new compression fracture in a vertebra adjacent to the operated vertebra.

In Japan, BKP is indicated in the acute phase of spinal compression fracture involving one vertebral body as a result of primary osteoporosis, when pain is not improved even after an adequate period of conservative treatment. Contraindications to BKP include pedicle fracture, fracture of a flat vertebra, fracture of the posterior wall of the vertebral body diagnosed on computed tomography, and cases in which a spinal reconstruction with internal fixation is not applicable. However, BKP used to treat osteoporotic burst fractures has been reported to yield clinically satisfactory results [19]. In addition, because there is no standard definition of “acute phase” and “adequate period of conservative treatment,” the treatment period is determined largely by the individual surgeon.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the risk factors for complications by studying postoperative clinical outcomes and to reconfirm the indications for and contraindications to BKP.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital (IRB approval no., 29-111). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Seventy-five patients who underwent BKP in Juntendo University Urayasu Hospital and Tobu Chiiki Hospital between July 2012 and September 2015 participated in this study. Patients who had no complications were assigned to the “uneventful” group, and those who had complications and persistent pain were assigned to the “eventful” group. We evaluated the risk factors for complications and persistent pain. The items we evaluated included the presence or absence of severe posterior wall injury, the presence or absence of pedicle fracture, the shape (flat or other) of the vertebral body, and the time period from the onset of pain to the BKP treatment. We also assessed for the occurrence of AVF, a complication frequently observed.

Data were analyzed with the IBM SPSS statistical program ver. 19.0 (IBM Japan Ltd., Tokyo, Japan); Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze differences between the eventful and uneventful groups in the incidences of severe posterior wall injury, pedicle fracture, and flattened vertebral body; in disease duration (less than 8 weeks versus longer); and in gender. A matched-pairs t-test was used to analyze differences between the eventful and uneventful groups in age, height, weight, and body mass index. Data are presented as means±standard deviations, and p<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Of the 75 patients, 49 were available for a follow-up period of 2 months or more. Of these 49 patients, 42 (85.7%) reported a decrease in their pain rating to 40 or less on the Visual Analog Scale within 4 days of the operation. However, there were some cases in which the pain recurred as a result of complications, such as AVF development. Twenty patients (40.8%) had an uneventful recovery, but the remaining 29 (59.2%) experienced prolonged pain or pain that recurred at least once. AVFs were found in 27 (55.1%) of the 49 patients; in seven of those patients, an AVF was observed on imaging examinations, but the affected patients did not complain of pain. The reasons for pain prolongation or relapse were AVF (in 20 patients), residual chronic lumbago (in five patients), kyphosis transformation (in three patients), and infection (in one patient). BKP was performed on six of the patients with AVF. In two of these, AVF recurred, which resulted in a third BKP procedure. Moreover, in two patients, spinal fusion was conducted for complications, including postoperative kyphosis transformation.

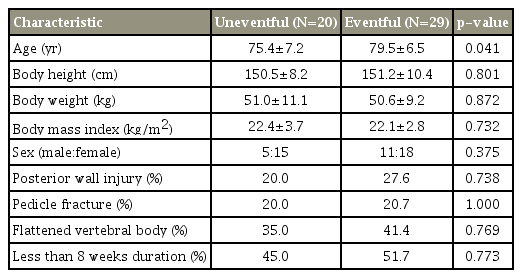

Table 1 lists the findings in the uneventful group and the eventful group. Patients in the eventful group were significantly older than those in the uneventful group.

There were no significant differences between the two groups in the incidences of severe posterior wall injury, pedicle fracture, or flattened vertebral body.

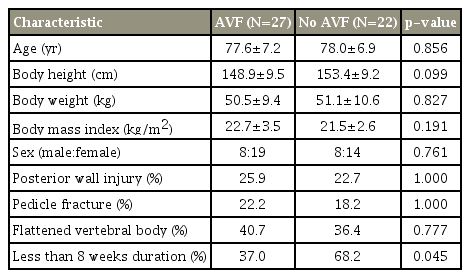

Next, the patients were grouped according to whether AVF had occurred (AVF group and no AVF group) (Table 2). There was a significant difference between the two groups in disease duration. The incidence of AVF was lower among patients with disease duration of less than 8 weeks.

Discussion

Because many reports have demonstrated excellent early relief of pain by BKP, this procedure is thought to contribute greatly to the maintenance and recovery of activities of daily living (ADLs) in elderly patients [1-12]. However, even if the therapeutic effect is considerable, it is necessary to reduce the risks associated with BKP or to limit the indication criteria if adverse effects are observed frequently.

We proactively performed BKP even on patients with moderately high surgical risks if pain from OVF caused difficulties in ADLs and the patients gave their informed consent. Some patients would not be able to tolerate a procedure more invasive than BKP, and without BKP, their performance of ADLs would remain poor because of strong residual pain. Therefore, some patients with eventful cases and high surgical risks did undergo BKP. This finding indicates that the priority in treatment with BKP should be on preventing complications, in addition to increasing the safety of the procedure.

In our hospital, one patient with severe pedicle fracture and posterior wall injury experienced postoperative worsening weakness of the lower limb muscles as a result of cement leakage into the spinal canal. (This case was excluded from the analysis because the patient transferred to another hospital and thus could not be monitored for 2 months or more.) Although pedicle fractures and severe posterior wall injuries were not significant risk factors for poor prognosis in this study, such serious complications should always be prevented. Therefore, we believe that patients with both pedicle fractures and severe posterior wall injuries should not undergo BKP.

In addition, one patient with bacterial infection had an iliopsoas muscle abscess 6 months before BKP surgery. The bacterial strain identified at the time of the abscess treatment was the same as that identified after the BKP procedure. It is thus necessary to take into consideration any history of bacterial infections in or around the spine before a patient undergoes BKP, as with other spinal instrumentation surgery.

In this study, four patients met the indication criteria—the absence of severe posterior wall injury or pedicle fracture, and no flattened vertebral body—and had had disease for more than 8 weeks. In all four cases, the patients developed AVF. We thus believe that the presence of indication criteria for BKP did not preclude AVF development.

Several reports have indicated potential risk factors for the development of AVF, including preoperative local kyphosis, hardness of the cement, low bone density, low body mass index, age, and cement leakage [13,18,20-24]. Of these, cement leakage was thought to play a role, inasmuch as the incidence of AVF was low among patients with short disease duration. In patients with disease longer than 8 weeks, cement leakage in the anterior portion of a vertebral body was often observed after BKP. Cement leaking from the front of the vertebral body then came into contact with the end plate of the adjacent vertebral body, causing a vertebral fracture in some patients. Patients with disease for less than 8 weeks actually had a similar incidence of cement leakage; however, the leakage was observed in the lateral aspect, not the anterior aspect, of the vertebral body in most of these cases, and so it was not the cause of AVF. In some of the patients with disease for more than 8 weeks, an intravertebral cleft was found in the anterior wall of the vertebral body. In such cases, caution is required because cement leakage is likely to occur.

Our study provides novel data suggesting that the incidence of AVF was low among patients with a disease duration of less than 8 weeks. Therefore, we thought that performing BKP soon after OVF occurrence reduced the risk for AVF. However, a recent study did not reveal evidence of an increased risk of fracture of any vertebral bodies, especially those adjacent to the treated vertebrae, after augmentation with either method in comparison with conservative treatment [25]. In any case, indications for BKP should be assessed with an index for prognosis with the use of tools such as magnetic resonance imaging and scoring systems in order to avoid unnecessary surgical treatment [26,27].

In our study, we focused on the comparison of shortterm postoperative outcomes. Further work is needed to evaluate long-term outcomes. The proportion of patients available for follow-up in our study was only 65.3. This rate was low because of age-related difficulties in continuing outpatient treatment after discharge and because patients with uneventful postoperative courses chose to discontinue treatment. In addition, in elderly patients who already had a history of OVF and poor spine alignment, it was difficult to assess the degree of pain because some pain was caused by preexisting conditions. Moreover, bone mineral density and anti-osteoporotic pharmacotherapy could not be clarified. These data should be included in future studies because these factors affect the results. We believe that accumulating more cases and extending the follow-up period would allow us to develop more effective treatment.

Conclusions

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of patients who underwent BKP in Japan in accordance with the indication criteria. We found that more than half of the patients had postoperative pain prolongation or recurrence, and the main cause was AVF. The possible risk factor for developing AVF was long disease duration; other indication criteria were not risk factors for AVF. However, because severe pedicle fracture, posterior wall injury, and infection could cause severe complications, patients with those conditions must be evaluated carefully before they undergo BKP. Although BKP in the early phase after injury was thought to produce a good outcome, unnecessary surgical treatment should be avoided, and the indications should be determined according to prognosis that is based on findings obtained with tools such as imaging examinations.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.