Surgical Correction of Fixed Kyphosis

Article information

Abstract

Study Design

A retrospective review was carried out on 23 patients with rigid fixed kyphosis who underwent surgical correction for their deformity.

Purpose

To report the results of surgical correction of fixed kyphosis according to the surgical approaches or methods.

Overview of Literature

Surgical correction of fixed kyphosis is more dangerous than the correction of any other spinal deformity because of the high incidence of paraplegia.

Methods

There were 12 cases of acute angular kyphosis (6 congenital, 6 healed tuberculosis) and 11 cases of round kyphosis (10 ankylosing spondylitis, 1 Scheuermann's kyphosis). Patients were excluded if their kyphosis was due to active tuberculosis, fractures, or degenerative lumbar changes. Operative procedures consisted of anterior, posterior and combined approaches with or without total vertebrectomy. Anterior procedure only was performed in 2 cases, while posterior procedure only was performed in 8 cases. Combined procedures were used in 13 cases, including 4 total vertebrectomies.

Results

The average kyphotic angle was 71.8° preoperatively, 31.0° postoperatively, and the average final angle was 39.2°. Thus, the correction rate was 57% and the correction loss rate was 12%. In acute angular kyphosis, correction rate of an anterior procedure only was 71%, correction rate of the combined procedures without total vertebrectomy was 49% and correction rate of the combined procedures with total vertebrectomy was 60%. In round kyphosis, correction rate of posterior procedure only was 65% and correction rate of combined procedures was 59%. The clinical results according to the Kirkaldy-Willis scale demonstrated 17 excellent outcomes, 5 good outcomes and one poor outcome.

Conclusions

Our data indicates that the combined approach and especially the total vertebrectomy showed the safety and the greatest correction rate if acute angular kyphosis was greater than 60 degrees.

Introduction

Many pathologic conditions can cause kyphotic deformities. However, acute angular kyphosis indicates a severe kyphosis that causes sagittal imbalance and results in progressive neurological alteration. Our data excludes kyphosis due to fracture, active tuberculosis, or degenerative lumbar disease. Fixed kyphosis consists of two distinct types according to morphology, acute angular kyphosis and round kyphosis. Congenital kyphosis and kyphosis as a sequela of healed tuberculosis show an acute angular morphology. However, Scheuermann's disease and ankylosing spondylitis result in round kyphosis. The purpose of surgical correction of fixed kyphosis is to correct the deformity as well as to prevent or alleviate paraplegia in severe acute angular kyphosis. The operation also improves respiratory and digestive function by relieving compressive effects of the deformity on the abdomen. However, the correction of this deformity is more dangerous than the correction of any other spinal deformity because of the high incidence of paraplegia. In considering the surgical correction of kyphosis, physicians must decide which approach is the best for that particular patient at that particular time. The purpose of this article is to report our results for the surgical correction of fixed kyphosis according to the surgical approaches or methods.

Materials and Methods

1. Materials

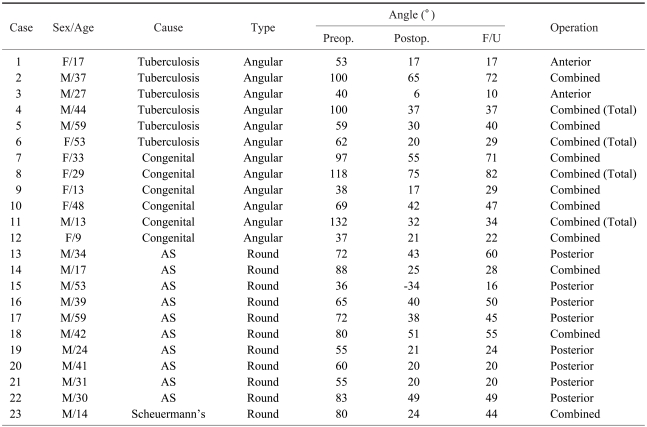

A retrospective review was carried out on 23 patients with rigid fixed kyphosis, with or without neurological compromise, who underwent surgical correction of their deformity from April 1988 to September 2002. The study subjects included 16 males and 7 females, with an average age of 33 years (range, 9~61 years). The average length of follow-up was 4.2 years (range, 2~7.2 years). There were 17 pure kyphosis cases and 6 cases of kyphosis combined with scoliosis. There were 12 cases of acute angular kyphosis (6 congenital, 6 healed tuberculosis) and 11 cases of round kyphosis (10 ankylosing spondylitis, 1 Scheuermann's kyphosis). Our data excludes kyphosis due to active tuberculosis, fractures, or degenerative lumbar changes (Table 1).

2. Methods

The correction of deformities was measured using Cobb's method, which determines the angle between the upper and lower end vertebrae. If the upper end vertebra existed beyond the 3rd thoracic vertebra, we indicated the 3rd thoracic vertebrae as the upper end vertebrae. The clinical results were evaluated using the Kirkaldy-Willis scale.

The kyphotic angles were analyzed as follows. The change between postoperative and preoperative angles was divided by the preoperative angle, and the resultant was designated as the correction rate. The change between the final follow-up correction rate and the postoperative correction rate was designated as the correction loss rate.

Operative procedures consisted of anterior only, posterior only, and a combined approach with or without total vertebrectomy, according to the characteristics of the patients' pathologies. Anterior procedure only was performed in 2 cases if acute angular kyphosis was 55 degrees or less without neurological loss. Posterior procedure only was performed in 8 cases of round kyphosis corrected by pedicle subtraction osteotomy. Combined procedures in acute angular kyphosis were performed in 10 cases, including 4 total vertebrectomies to correct the severe deformity. And combined procedures in round kyphosis were performed in 3 cases if round kyphosis was greater than 80 degrees.

Results

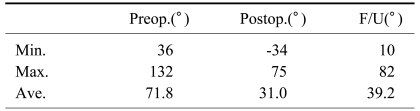

The average kyphotic angle was 71.8° (range, 36° to 132°) preoperatively, 31.0° (range, -34° to 75°) postoperatively, and the average final angle was 39.2° (range, 10° to 82°). Thus, the correction rate was 57% and the correction loss rate was 12% (Table 2).

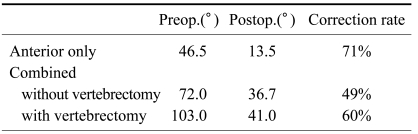

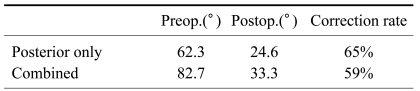

In acute angular kyphosis, the combined procedures without total vertebrectomy yielded a correction rate of 49%, whereas the total vertebrectomy correction rate was 60%, which is an improvement over the combined procedures without vertebrectomy (Table 3). In round kyphosis, posterior procedure only (pedicle subtraction osteotomy) yielded a correction rate of 65%, whereas combined procedures (multiple anterior release, multiple posterior segmental osteotomy and instrumented correction) yielded a correction rate of 59% (Table 4).

The clinical results accorging to the Kirkaldy-Willis scale demonstrated 17 excellent outcomes, 5 good outcomes, and one poor outcome. Five cases demonstrated preoperative neurological deficits, but all five experienced a complete improvement in neurological status after correction of their kyphosis. Complications were encountered in 4 cases: one subject developed incomplete paraplegia and required a wheelchair for ambulation, one subject had Brown-Sequard syndrome that recovered in 1 year, one subject had a pseudarthrosis and one subject experienced acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Discussion

Kyphosis is classified as pure kyphosis and kyphoscoliosis, or as acute angular kyphosis and round kyphosis, according to the morphology of the deformity. Congenital kyphosis and kyphosis as a sequela of healed tuberculosis show acute angular morphology, while Scheuermann's disease and ankylosing spondylitis demonstrate round kyphosis morphology. Within this study, there were 12 cases of acute angular kyphosis (6 congenital, 6 healed tuberculosis) and 11 cases of round kyphosis (10 ankylosing spondylitis, 1 Scheuermann's kyphosis). Although these diseases are rare, they are serious and require prompt attention. Without proper timing of treatment, the natural course of acute angular kyphosis may lead to neurological deficits and ultimately complete paraplegia, mandating active intervention. This neurological alteration is most commonly observed in the acute angular form of kyphosis. In this study, paraparesis was noted in 5 cases of acute angular kyphosis ( 1 congenital, 4 kyphosis from healed tuberculosis).

Congenital kyphoscoliosis was first noticed in 1844 by Von Rokitansky. In 1955, James1 reported 21 cases of this condition and, in 1973, Winter et al.2 made great advances in the treatment of this disease by analyzing 130 cases.

Van Schrick3 classified congenital kyphosis into two groups: type 1 (a failure of segmentation) and type 2 (defective formation of vertebral bodies). Later, Winter et al.2 reworked the classification, including a third group of mixed etiology. His classification was as follows: type 1 (failure of formation), type 2 (failure of segmentation) and type 3 (mixed type). These classifications are clinically important because each type has a different natural progression of curvature and potential for neurological deficits. Within this study, 3 cases were type 1 and 1 case was type 3, according to Winter's classification. Among these cases, 3 subjects were combined with scoliosis. Because only surgery can prevent the progression of deformities, surgery should be performed before this progression occurs. The type and timing of operation differs according to the cause and severity of curvature and the age of the patients2.

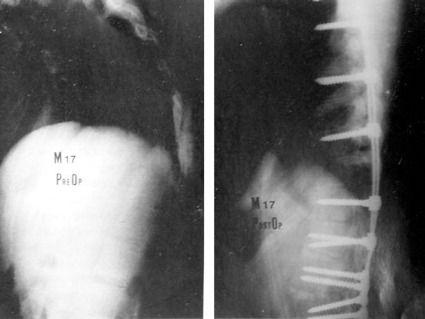

Winter4, Winter and Moe5, and Winter et al.2 recommended only posterior fusion in type 2 congenital kyphosis with no need for correction. A posterior fusion extending one vertebra cranial and one caudal to the segmentation defect is ideal. However, when the kyphosis presents later with a significant deformity that needs correction, a combined approach is best. In type 1 deformities, posterior fusion alone by means of convex growth arrest without instrumentation can be performed on patients under 5 years of age and with Kyphosis under 50 degrees. Winter et al.6 and Winter et al.7 said that in children older than 5 years with less severe kyphosis (under 55 degrees), a posterior fusion alone can successfully control the kyphosis and stabilize the curve of the spine. For kyphosis greater than 55 degrees, an anterior and posterior fusion is necessary, especially in adults. Within this study, we had 6 cases of congenital kyphosis, all of which were greater than 55 degrees demonstrating rigidity in flexion and extension lateral X-ray, and therefore needed both anterior and posterior approaches (Fig. 1).

Thirty-three-year-old female patient. Initial X-ray showed acute angular kyphosis of congenital cause with a kyphotic angle of 97 degrees. In the postoperative X-ray, the kyphotic angle was corrected to 55 degrees using the combined approach.

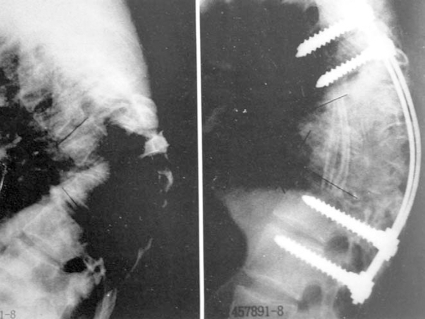

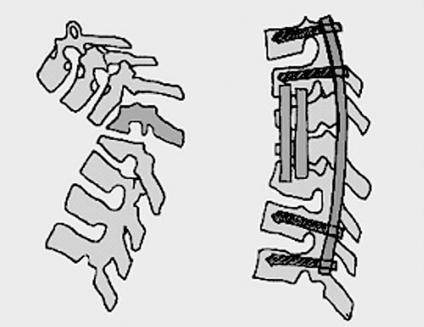

We performed total vertebrectomies in 4 cases of severe rigid kyphosis. This technique included removal of the vertebral body, disc and pedicles via an anterior approach and removal of the posterior elements and remaining pedicles via a posterior approach (Fig. 2). Because the contracted ALL, the annulus fibrosus and the fibrocartilage filling the defect were removed during the anterior approach, the posterior correction of deformity was easier and the risk of paraplegia was reduced (Figs. 3 and 4).

Schematic diagram of the total vertebrectomy procedures. This technique included removal of vertebral body, intervertebral disc and pedicles, and used an autogenous fibular bone graft via an anterior approach. After then insertion of an instrument and removal of the posterior elements and remaining pedicles, and subsequently compressed the rod to achieve the correction of deformity via a posterior approach.

(A) Initial X-ray showed acute angular kyphosis and scoliosis of congenital cause with 132 degrees of kyphotic angle and 60 degrees of scoliotic angle. (B) In postop. X-ray, kyphotic and scoliotic angle are corrected 32 degrees and 27 degrees, respectively using the combined approach with total vertebrectomy.

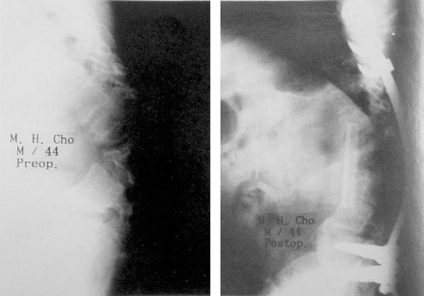

Forty-four-year-old male patient. Initial X-ray showed acute angular kyphosis due to healed tuberculosis with a kyphotic angle of 100 degrees. In postoperative X-ray, the kyphotic angle was corrected to 37 degrees using the combined approach with total vertebrectomy.

Paraplegia is a possible complication after the correction of kyphotic deformity. Lonstein8 explained that during the correction, especially when the apex of the kyphosis is rigid, only areas other than the area except apex is corrected. In that case, as the extending spinal cord moves anteriorly, the remaining rigid apex may cause mechanical compression and altered blood supply to the spinal cord. Furthermore, extension and compression of the spinal cord reduces the diameter of blood vessels, which may interfere with venous return. This may cause spinal edema and further decreased blood supply resulting in hypoxia or ischemia of the spinal cord. Winter et al.2 reported paraplegia after correction of kyphosis in 3% of 94 patients, and Montgomery and Hall9 reported paraplegia in 12% of 25 patients. We encountered 2 cases of incomplete postoperative paraplegia out of 23 patients, presumably resulting from mechanical compression and reduced blood supply. We performed a total vertebrectomy in order to maximize correction and minimize the chance of paraplegia, as suggested by Winter and McBride10 and Bradford11. This procedure is known to be the most efficient correction of kyphotic deformity. However, the instability produced by total removal of the bony structure may cause spinal cord injury. To prevent any unexpected spinal cord injury, we inserted a Zielke or Harrington compression rod prior to removal of the posterior elements and subsequently compressed the rod. This compression of the posterior elements reduces the risk of spinal cord extension and makes the correction safer.

Another potential complication after deformity correction is pseudarthrosis. Montgomery and Hall reported a rate of 7% for this complication. Winter reported a rate of 41% in posterior fusion alone and 8% in the combined approach. We showed rigid fusion in all cases but one.

Tuberculous spondylitis during childhood destroys the anterior vertebral bodies and thus limits anterior growth potential and induce the unsegmented bar effect due to the continuing growth of posterior column. Therefore, this condition results in an acute angular kyphosis that progresses until the end of growth. This increase of the kyphotic angle can cause pulmonary insufficiency and neurological deficits12. Within this study, 6 cases had kyphotic deformities due to healed tuberculosis; 4 of which had preoperative paraparesis and 2 of which had pulmonary insufficiency. Treatment was focused on removal of the primary lesion. To correct the rigid kyphotic deformity, O'Brien12 used Halo-pelvic traction for progressive correction. We used an anterior procedure alone when indicated by the region of deformity especially with an angle of 55 degrees or less without neurologic loss. An anterior approach is advantageous when possible in that kyphosis and sagittal balance can be corrected effectively with short segmental fusion. We were able to obtain effective correction using the anterior procedure alone in 2 cases. However, in 4 cases with angulation greater than 55 degrees, or with preoperative neurologic deficits, a combined anterior and posterior approach was used of which required total vertebrectomy because of severe rigidity. Among these 6 cases, we used an autogenous fibular bone graft for reinforcement of the defect from extensive anterior decompression, which had been introduced by Streitz et al.13.

We corrected 11 round kyphosis; 10 cases of ankylosing spondylitis and 1 case of Scheuermann's kyphosis. Almost all ankylosing spondylitis patients have a benign clinical course in which progression of the disease stops in a mild form that does not alter their life expectancy or lead to loss of function14. However, if the spine is ankylosed in the kyphotic posture to the extent that the patient's field of vision is limited to the floor, surgery is the only therapeutic option. Accordingly, prevention is critical for patients with this condition. The goal of surgery is to reduce discomfort arising from bad posture and to enhance digestive and pulmonary function. To correct the deformity, the osteotomy site is selected according to the site of the deformity. However, lumbar osteotomy is safer than cervical or thoracic osteotomy. Therefore, a posterior lumbar osteotomy (pedicle subtraction osteotomy) is performed when deemed effective and the 2nd or 3rd vertebra is preferred15.

Current osteotomy techniques include the Smith-Petersen et al.16 osteotomy, the La Chapelle17, Briggs et al.18 posterior wedge osteotomy, etc. These techniques spread the anterior column, increasing the risk of extension of important vessels anteriorly and cauda eqina caudally, and posing a risk of ischemic bowel caused by obstruction of the superior mesenteric artery. To avoid these complications, Thomasen19 introduced the pedicle subtraction osteotomy and Puschel and Zielke20 performed the multiple segment osteotomy. In our country, Cho15 first reported cases corrected by Thomasen's pedicle subtraction osteotomy and by multiple segment osteotomy.

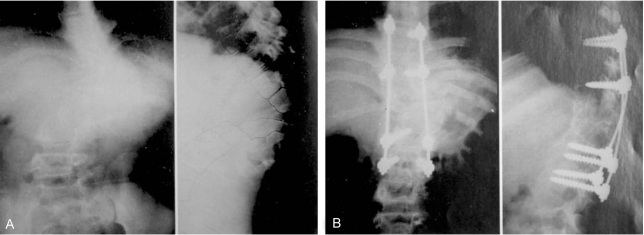

When the deformity is confined to the cervical area and the lumbar osteotomy seems to be ineffective, osteotomy of cervical spine can be performed. In this case, the most common technique involves applying a Halo-cast first, performing cervical osteotomy under local anesthesia, and then correcting the deformity with modulation of the Halo-cast21. Multiple segment osteotomy is safer than one segment osteotomy in the thoracic spine. An anterior or a combined approach is used according to the rigidity. After osteotomy, Harrington compression rods, Zielke instrumentation, Luque wire or C-D can be used, each with advantages and disadvantages. In our country, Chung et al.22 reported 5 cases of multiple segment osteotomy. We performed the Thomasen technique in 8 cases, obtaining excellent correction (Fig. 5), and 2 multiple segment osteotomies (Fig. 6).

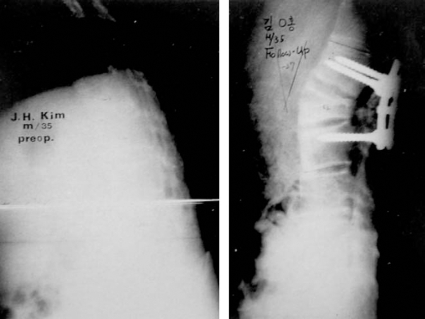

Thirty-five-year-old male patient. Initial X-ray showed round kyphosis due to ankylosing spondylitis with a kyphotic angle of 21 degrees in the lumbar region. In postoperative X-ray, kyphotic angle is corrected to 27 degrees for the lordotic angle using the posterior approach.

Conclusions

Correction of fixed kyphosis is possible, but involves a challenging operation with a high risk of paraplegia. However, without surgery, severe kyphotic deformity itself can cause chronic spinal cord compression at the apex of the deformity, producing progressive neurological deficits ultimately leading to paraplegia. Therefore, surgery should be considered in all patients with this deformity as a preventative measure. Before surgery, the advantages and possible complications of the procedure and the natural course of the deformity itself must be fully discussed with the patients and their families. To achieve correction of severe acute angular deformity with greater than 60 degrees of angulation and to prevent progressive neurological sequelae, the combined approach with the total vertebrectomy showed the safety and the greatest correction rate.