An Updated Overview of Low Back Pain Management in Primary Care

Article information

Abstract

Currently, guidelines for lower back pain (LBP) treatment are needed. We reviewed the current guidelines and high-quality articles to confirm the LBP guidelines for the Korean Society of Spine Surgery. We searched available databases for high-quality articles in English on LBP published from 2000 to the present year. Literature searches using these guidelines included studies from MEDLINE, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and Embase. We analyzed a total of 132 randomized clinical trials, 116 systematic reviews, 9 meta-analyses, and 4 clinical guideline reviews. We adopted the SIGN checklist for the assessment of article quality. Data were subsequently abstracted by a reviewer and verified. Many treatment options exist for LBP, with a variety of recommendation grades. We assessed the recommendation grade for general behavior, pharmacological therapy, psychological therapy, and specific exercises. This information should be helpful to physicians in the treatment of LBP patients.

Introduction

Currently, there are many guidelines for the treatment of lower back pain (LBP). Many of these guidelines are focused on medication; however, other treatment modalities should also be evaluated [1234]. In addition, while there are many treatment options for LBP treatment, the majority of options are based upon neuropathic pain and radiculopathy. To create an up-to-date guideline for primary LBP treatments, we reviewed previously published guidelines and added information from recently published high-quality studies.

Materials and Methods

1. Data sources and searches

The literature search included all English-language articles on LBP. We searched MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for relevant systematic reviews, combining terms for LBP with a search strategy for identifying systematic reviews. When higher-quality systematic reviews were not available for a particular treatment, we conducted additional searches for primary studies of the randomized controlled trials. We excluded trials of LBP associated with neuropathic pain. Due to the large number of trials evaluating medications for LBP, our primary source for trials was clinical guideline reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses. When a higher-quality systematic review was not available for a particular intervention, we included all relevant randomized controlled trials. We included randomized controlled trials that met all of the following criteria: (1) reported in English and (2) evaluated a target treatment. We excluded outdated reviews. We also excluded reviews that did not clearly use systematic methods as well as systematic reviews that evaluated target medications but did not report results specifically for patients with LBP. We analyzed a total of 132 randomized controlled trials, 116 systematic reviews, 9 meta-analyses, and 4 clinical guideline reviews.

2. Data extraction and quality assessment

An expert panel convened by the Korean Society of Spine Surgery (KSSS) determined which treatments would be included in this review. Data were subsequently abstracted by reviewers and verified. For each trial, we differentiated between acute (4 weeks in duration) and chronic/subacute (4 weeks in duration) LBP. If specific data on the duration of trials were not provided, we relied on the categorization (acute or chronic/subacute) assigned by the articles. We assessed the internal validity (quality) of systematic reviews using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) criteria (Table 1) [5]. There were many treatment options for LBP, with a variety of recommendation grades. We assessed recommendation grades for general behavior, pharmacological therapy, psychological therapy, and specific exercises. We assessed the overall strength of evidence for a body of evidence using methods adapted from the SIGN criteria [5]. To evaluate consistency, we classified the conclusions of trials and systematic reviews as A, B, C, and D. If we could not determine the recommendation level due to the lack of high-quality articles, we defined it as insufficient (I).

Results

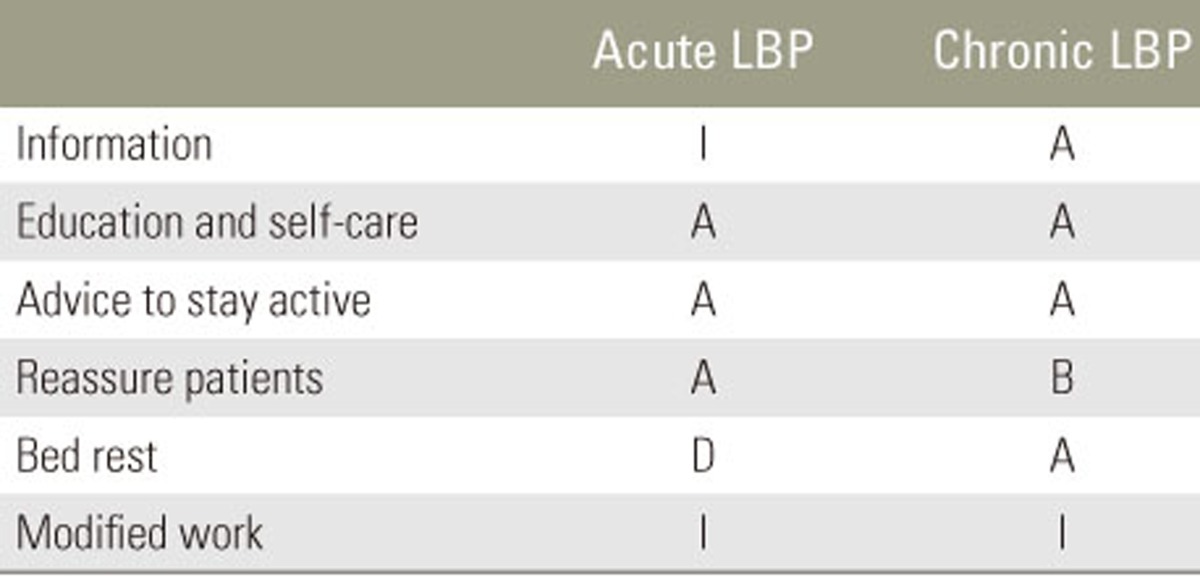

1. General behavior

We reviewed six treatment methods for acute and chronic LBP (Table 1). For acute LBP, four unique trials of general behavior and three clinical guideline reviews were included in the review for general behavior [2346789]. Four trials found clear differences in pain relief with education and self-care and advice to stay active. In addition, there was sufficient evidence from three clinical guideline reviews to support the effectiveness of reassuring patients. However, there was insufficient evidence for bed rest and modified work based upon the available references. For chronic LBP, two higher-quality trials found evidence for effectiveness of education and self-care and the advice to stay active. In addition, two clinical guideline reviews highly supported the use of information, reassuring patients, and bed rest for the treatment of chronic LBP [1268].

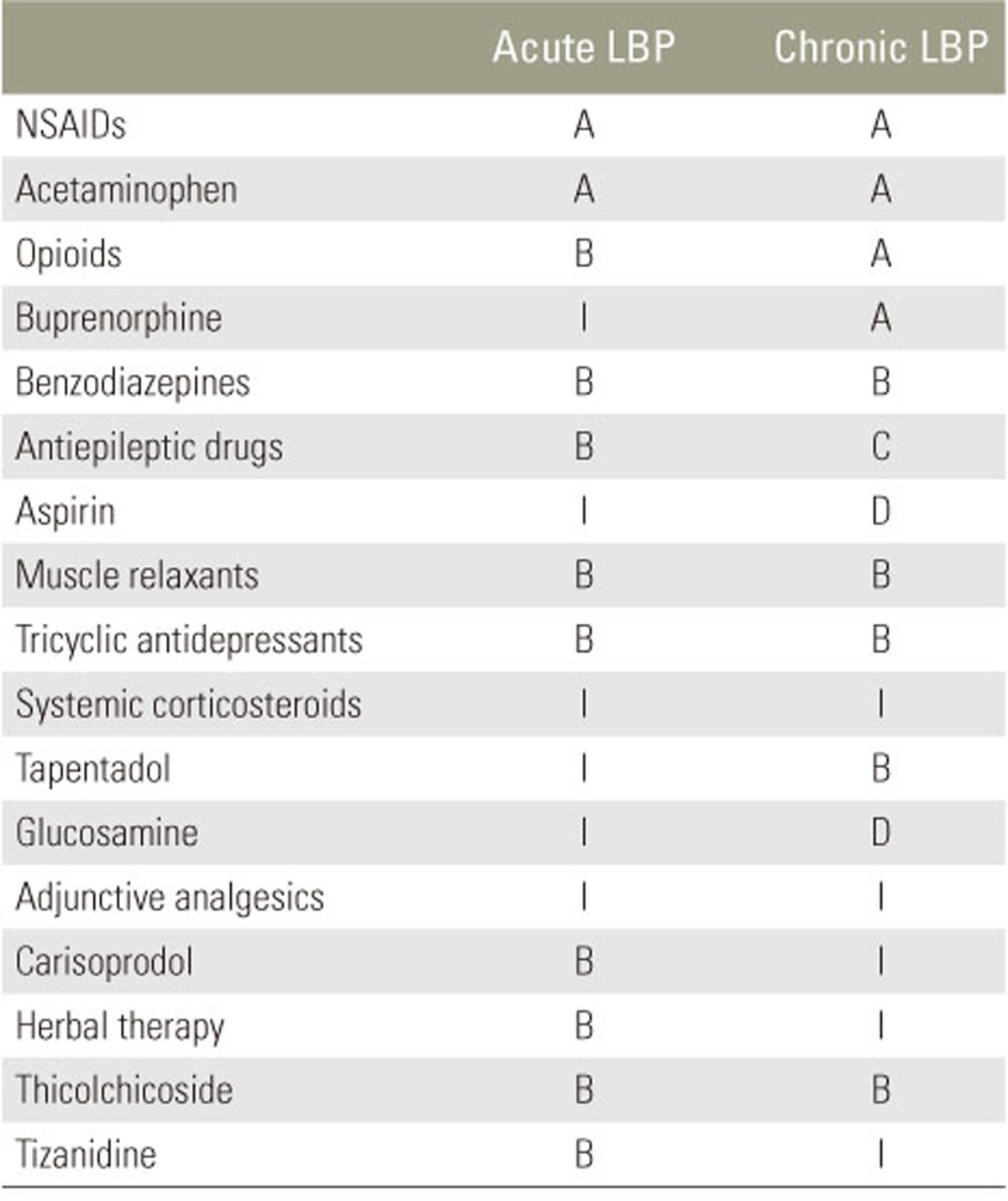

2. Pharmacological therapy

A total of 18 methods for the treatment of acute and chronic LBP were reviewed by the assessment panel [23410111213141516171819]. For acute LBP, several randomized trials and higher-quality systematic reviews found non-steroidal anti-inflammatory dru gs (NSAIDs), acetaminophen (AAP), and paracetamol superior for pain relief (Table 2). In addition, three clinical guideline reviews strongly supported the use of these medications. Opioids, benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, and tricyclic antidepressants showed significant improvement of symptoms in two high-quality systemic reviews as well as three clinical guidelines. In addition, three trials and one clinical guideline review found minimal differences in pain relief with the use of carisoprodol, herbal therapy, thiocolchicoside, and tizanidine. For chronic LBP, several randomized trials and higher-quality systematic reviews found NSAIDs, AAP, paracetamol, opioid, and buprenorphine superior for pain relief. Benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, tricyclic antidepressants, tapentadol, and pregabalin showed significant improvement of symptoms in seven high-quality studies as well as three clinical guidelines. Other pharmacological therapies were not supported by the references [12411161719202122232425262728293031323334353637383940].

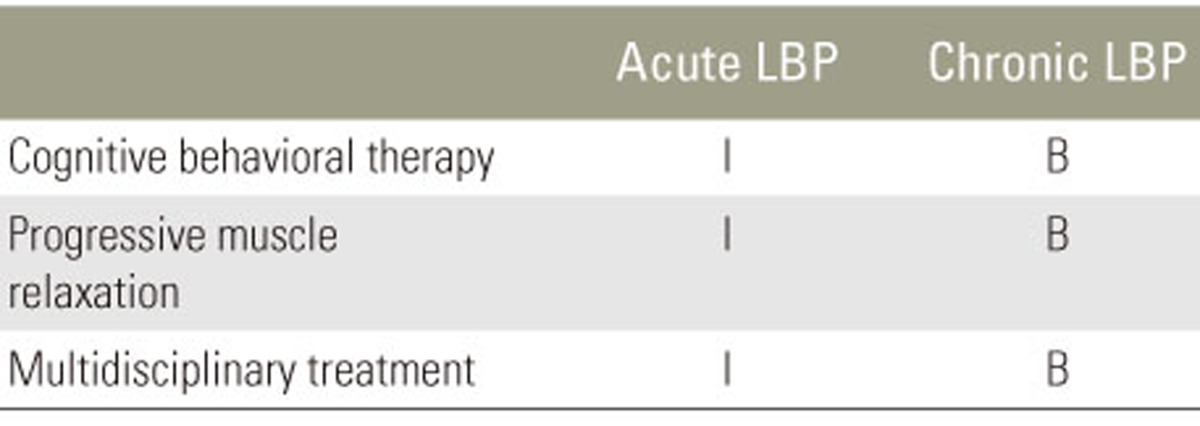

3. Psychological therapy

We reviewed three methods for the treatment of acute and chronic LBP [1341641424344]. For acute LBP, the evidence was insufficient from several reviews of clinical guidelines for the effectiveness of psychological therapy (Table 3). For chronic LBP, five higher-quality trials found evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy. In addition, three clinical guideline reviews highly supported the use of cognitive behavioral therapy. Progressive muscle relaxation was supported by one clinical guideline review, with multidisciplinary treatments supported by one high-quality randomized trial.

4. Specific exercise

We reviewed 11 treatment methods for the treatment of acute and chronic LBP [23474546474849505152]. For acute LBP, six unique trials of general behavior and two clinical guideline reviews were included in the review of general exercise (Table 4). The evidence was insufficient from several randomized trials and clinical guideline reviews to support the effectiveness of a specific exercise for acute LBP. A total of 12 trials found clear differences in pain relief with general exercise for chronic LBP. In addition, there was sufficient evidence from two meta-analyses, three systematic reviews, and three clinical guideline reviews to support the effectiveness of general exercise. We identified two randomized trials and two clinical guideline reviews for aquatic and supervised exercise therapy. In addition, seven randomized trials supported the effectiveness of stabilizing exercises. Other treatment options were not supported by the available literature [234464748495051525354555657585960616263646566676869].

Discussion

There were several guidelines for LBP. Most clinical guideline reviews were based upon extensive literature searches. The Cochrane reviews are frequently used as well as databases such as MEDLINE and Embase. As in our study, literature reviews of high-quality trials and previous guidelines are used for additional searches. A variety of committees use different weighting systems and ratings of the available evidence with some variations in the manner recommendations are presented [1234]. In some reviews, all recommendations are linked with references, and in others, a general remark is made for a given recommendation. We reviewed the current guidelines and high-quality articles to confirm the LBP guidelines for the KSSS. The primary aim of this study was the establishment of updated clinical guidelines for the management of LBP in primary care. Clinical guidelines, which focused on interventional or surgical treatment, occupational care settings, or specific subgroups of patients with radicular pain by a specific disease, were not considered. Separate studies need to be undertaken to present an overview for all treatment modalities. SIGN guidelines are developed using an explicit methodology based on three core principles: (1) development is by multidisciplinary, nationally representative groups; (2) a systematic review is conducted to identify and critically appraise the evidence; and (3) recommendations are explicitly linked to the supporting evidence. These principles have remained constant since SIGN was first established. A statement is provided for the implementation of the principles of the GRADE process. SIGN guidelines are based on systematic review of the evidence, undertaken by guideline development group members, and with support from the SIGN Executives [5].

Most published guidelines have discussed a good prognosis of LBP. For patients with longer duration of LBP or recurrent LBP, the prognosis may be less favorable. We reviewed several treatment methods for the treatment of acute and chronic LBP. Support for the consensus meeting on which this article is based was provided by the KSSS group, which received unrestricted support from multiple pharmaceutical companies. There was sufficient evidence from several randomized trials and clinical guideline reviews that support the effectiveness of treatment options. For example, several trials found clear differences in pain relief with general exercise for chronic LBP. In addition, there was sufficient evidence from meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and clinical guideline reviews that support the effectiveness of general exercise. More sophisticated estimates of LBP prognosis may be needed in the future. Recommendations did not support the use of injections, minimally invasive approaches, or surgical procedures for LBP. These treatment options were not included in this review. Future reviewer panels may wish to provide additional guidance on what constitutes appropriate surgical or interventional management and acceptable improvement for various time intervals. Although this does not eliminate the possibility that individual patients may benefit from interventions or surgery, current adherence to these recommendations by clinicians appears minimal.

Conclusions

We assessed the recommendation grade for the primary treatment of acute and chronic LBP. A variety of recommendation grades were determined for general behavior, pharmacological therapy, psychological therapy, and specific exercises. This analysis should be helpful to physicians in the treatment of LBP.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.