Non-Caseating Granulomatous Infective Spondylitis: Melioidotic Spondylitis

Article information

Abstract

Study Design

Retrospective clinical analysis.

Purpose

To delineate the clinical presentation of melioidosis in the spine and to create awareness among healthcare professionals, particularly spine surgeons, regarding the diagnosis and treatment of melioidotic spondylitis.

Overview of Literature

Melioidosis is an emerging disease, particularly in developing countries, associated with a high mortality rate. Its causative pathogen, Burkholderia pseudomallei, has been labeled as a bio-terrorism agent.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients who were culture positive for B. pseudomallei. Assessment of patients was performed using clinical, radiological, and blood parameters. Clinical measures included pain, neurological deficit, and return to work. Radiological measures included plain radiography of the spine and magnetic resonance imaging. Blood tests included erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels.

Results

Four patients having melioidosis with spondylitis were evaluated. All of them had diabetes mellitus; three had multiple abscesses which required incision and drainage. Their clinical spectrum was similar to that of tuberculous spondylitis; all had back pain and radiology revealed infective spondylodiscitis with prevertebral and paravertebral collections with psoas abscess. Three patients underwent ultrasound-guided drainage of the psoas abscess and one had aspiration of the subcutaneous abscess. Bacteriological cultures showed presence of B. pseudomallei, and histopathology showed non-caseating granulomatous inflammation. All patients were treated with intravenous Ceftazidime for 2 weeks, followed by oral bactrim double strength and Doxycycline for 20 weeks. All patients improved with treatment and were healed at follow up.

Conclusions

Melioidosis presents with a clinical spectrum similar to that of tuberculosis. A diagnosis of melioidotic spondylitis should be considered, particularly in patients with diabetes with neutrophilic leukocytosis and clinical-radiological features suggestive of infective spondylodiscitis. Bacteriological culture and histopathology helps in differentiating the two conditions. Health education for healthcare professionals is important for correctly diagnosing this disease.

Introduction

Melioidosis is a bacterial disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, an intracellular gram-negative pathogen, which is associated with a wide clinical spectrum, from subcutaneous tissue collections to rapidly progressive septicemia [1]. Although several reports describe the multisystem involvement of melioidosis in detail [123], few cases of melioidotic spondylitis have been reported [456]. Histopathologically, melioidotic spondylitis presents as a non-caseating, granulomatous inflammation that is frequently confused with tuberculous spondylitis. The aim of this study is to delineate the clinical presentation of melioidosis in the spine and to create awareness among health care professionals, particularly spine surgeons, about the diagnosis and treatment of melioidotic spondylitis.

Materials and Methods

This study consisted of a retrospective analysis of patients with culture proven melioidotic spondylitis who were treated at Christian Medical College and Hospital, Vellore in Southern India over a period of 5 years (from January 2009 to December 2014). Their clinical presentation, demographic profile, risk factors, laboratory findings, bacteriological cultures, histopathological reports, and treatment strategies and outcomes were analyzed in detail.

Results

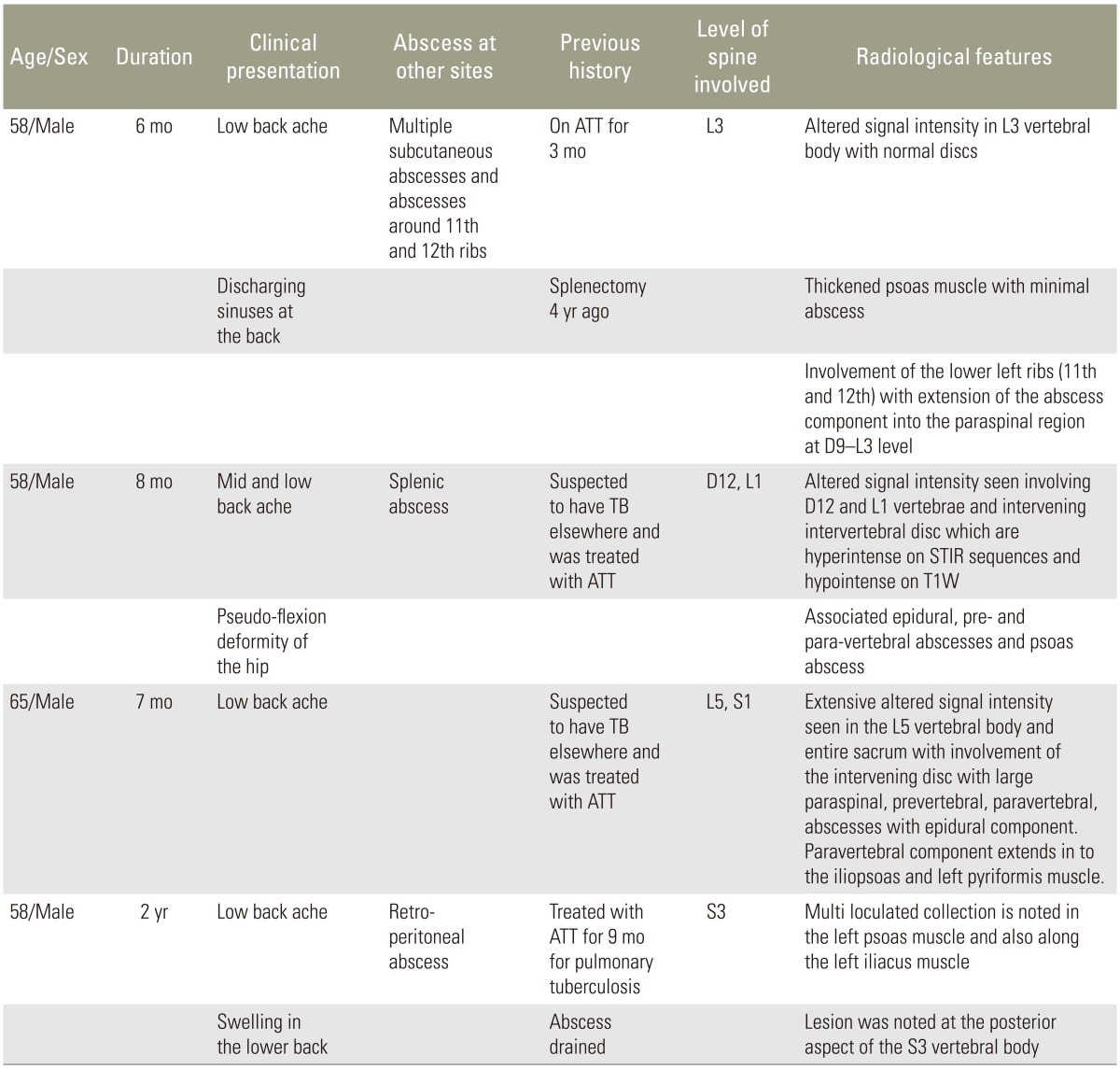

During the study period, 890 patients with tuberculous spondylitis and 210 patients with pyogenic spondylodiscitis were treated in the Department of Orthopaedics. Diagnosis was confirmed by bacteriological cultures with or without histopathological evidence. Four patients (prevalence, 0.36%) with culture proven melioidotic spondylitis were identified. All were males, with a mean age of 54 years (range, 39–65 years), from North-Eastern India, none of them were farmers. All patients presented with fever and back pain along with associated constitutional symptoms, such as loss of weight and appetite. Two of them presented with multiple discharging sinuses; three had multiple abscesses elsewhere (prostate, spleen, and subcutaneous spaces) which had been treated earlier with drainage and anti-tuberculous chemotherapy (empirically for 6 months) with no clinical improvement. None of the patients had any overt neurological deficit. Their clinical and radiological features are described in detail in Table 1.

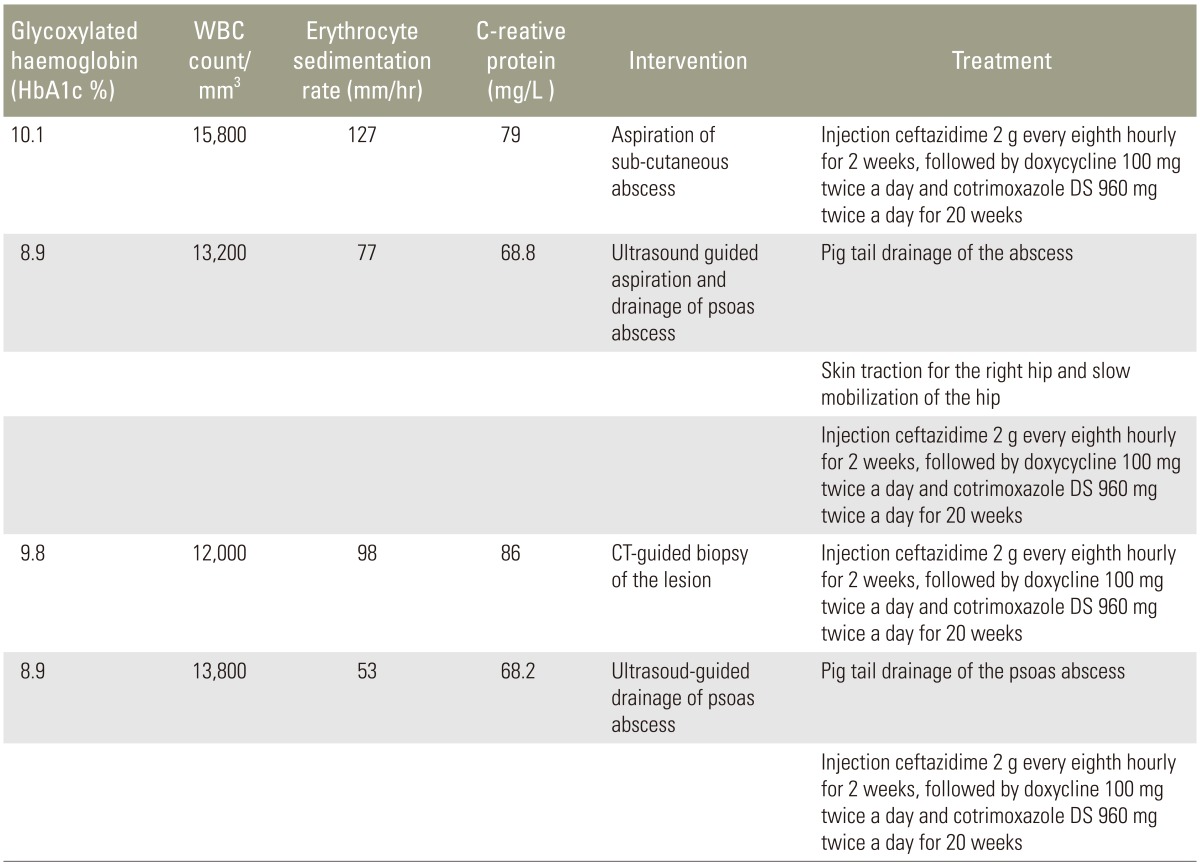

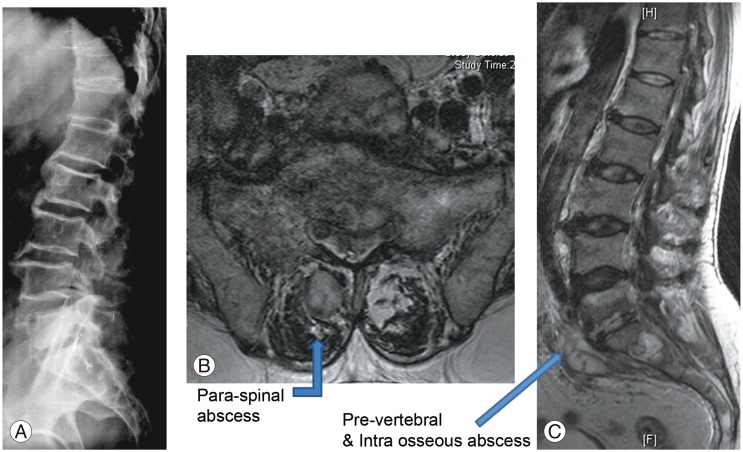

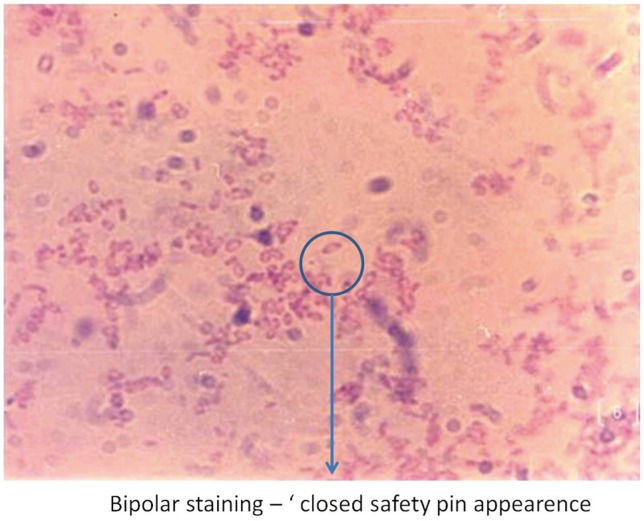

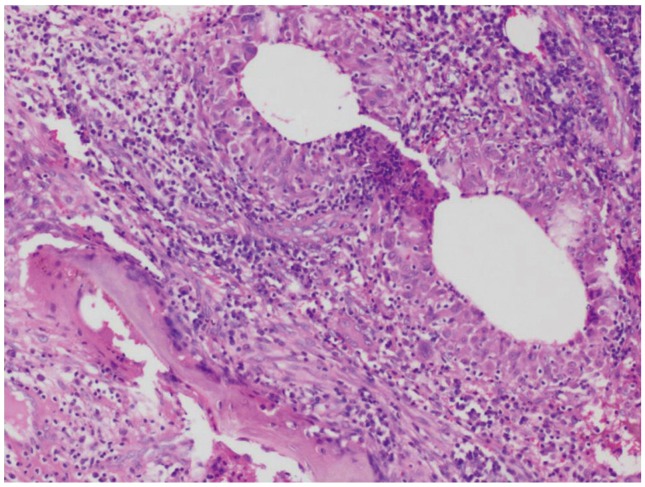

Blood analysis revealed neutrophilic leukocytosis (>75%), with elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (mean, 88 mm/hr; reference value, 30–40 mm/hr for adults) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (mean, 75.5 mg/L; reference value, <6 mg/L). All patients had uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (HbA1c >9.4) (Table 2). Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine showed paradiscal involvement in two patients (with plain radiograph revealing disc space narrowing) (Fig. 1A) and vertebral body involvement (central type) in the other two patients. Paravertebral and psoas abscesses were evident in three patients (Fig. 1B, C). All patients were clinically suspected to have active hematogenous infective spondylodiscitis, probably of tuberculous etiology. One patient underwent local aspiration of a subcutaneous abscess, another underwent computed tomography–guided biopsy of the lesion, and the remaining two had ultrasound-guided aspiration and Malecot catheter drainage (pig tail drainage) of the psoas abscess (Tables 1, 2). Tissue and fluid samples were sent for microbiological and histopathological confirmatory tests. Smears stained with dilute carbol fuchsin revealed a typical “safety pin appearance” (Fig. 2), and all cultures showed the presence of B. pseudomallei growing as smooth pink colonies in B. pseudomallei selective agar, as smooth, opaque white colonies in blood agar (Fig. 3A), or as pink colonies in MacConkey agar (Fig. 3B). The bacterium was sensitive to Ceftazidime and Doxycycline, resistant to Ciprofloxacin and Gentamycin, and biopsy samples revealed non-caseating granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 4).

Radiological findings. (A) Lateral view of the lumbosacral spine showing decreased L5–S1 disc space. (B, C) T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the axial and sagittal sections revealing L5–S1 infective spondylodiscitis with pre- and paravertebral abscesses.

Dilute carbol fuchsin staining demonstrating Burkholderia pseudomallei's typical “safety pin appearance” (bipolar staining, 512 ×323).

Bacterial cultures. (A) Smooth, white colony growth on blood agar. (B) Serial growth as pink colonies on MacConkey agar (24, 48, and 96 hours).

Histopathology image revealing non-caseous granulomatous inflammation in the intertrabecular spaces (H&E, ×100).

Patients were treated with intravenous Ceftazidime (2 g every 8 hours for 2 weeks, followed by Doxycycline [100 mg twice a day]) and Cotrimoxazole double strength (960 mg twice a day) for 20 weeks as per the recommended regimen [78].

All patients showed symptomatic improvement at follow-up. They were assessed clinically and radiologically, and blood tests were performed to monitor ESR and CRP levels. Two patients returned for follow-up; one was disease-free and the other showed residual psoas abscess. The remaining two patients were asymptomatic, as determined via telephonic interview. The average duration of follow up was 2 years.

Discussion

Melioidosis is regarded to be endemic to Northern Australia and Southeast Asia, and is an emerging disease in developing countries like India [9], where it is still underdiagnosed mainly because of the lack of awareness, low index of suspicion, and inadequate laboratory facilities [10].

Melioidotic infection preponderantly occurs in males, usually by inoculation through skin abrasions or by inhalation [7]. There are multiple risk factors associated with the disease, such as diabetes mellitus; intravenous drug abuse; steroid use; rainfall [4]; exposure to contaminated soil [7]; rice farming; hematological malignancies; excessive alcohol intake; and chronic liver, kidney, or respiratory disease. In our study, male gender and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus (HBA1c >8.3) were the only specific risk factors identified.

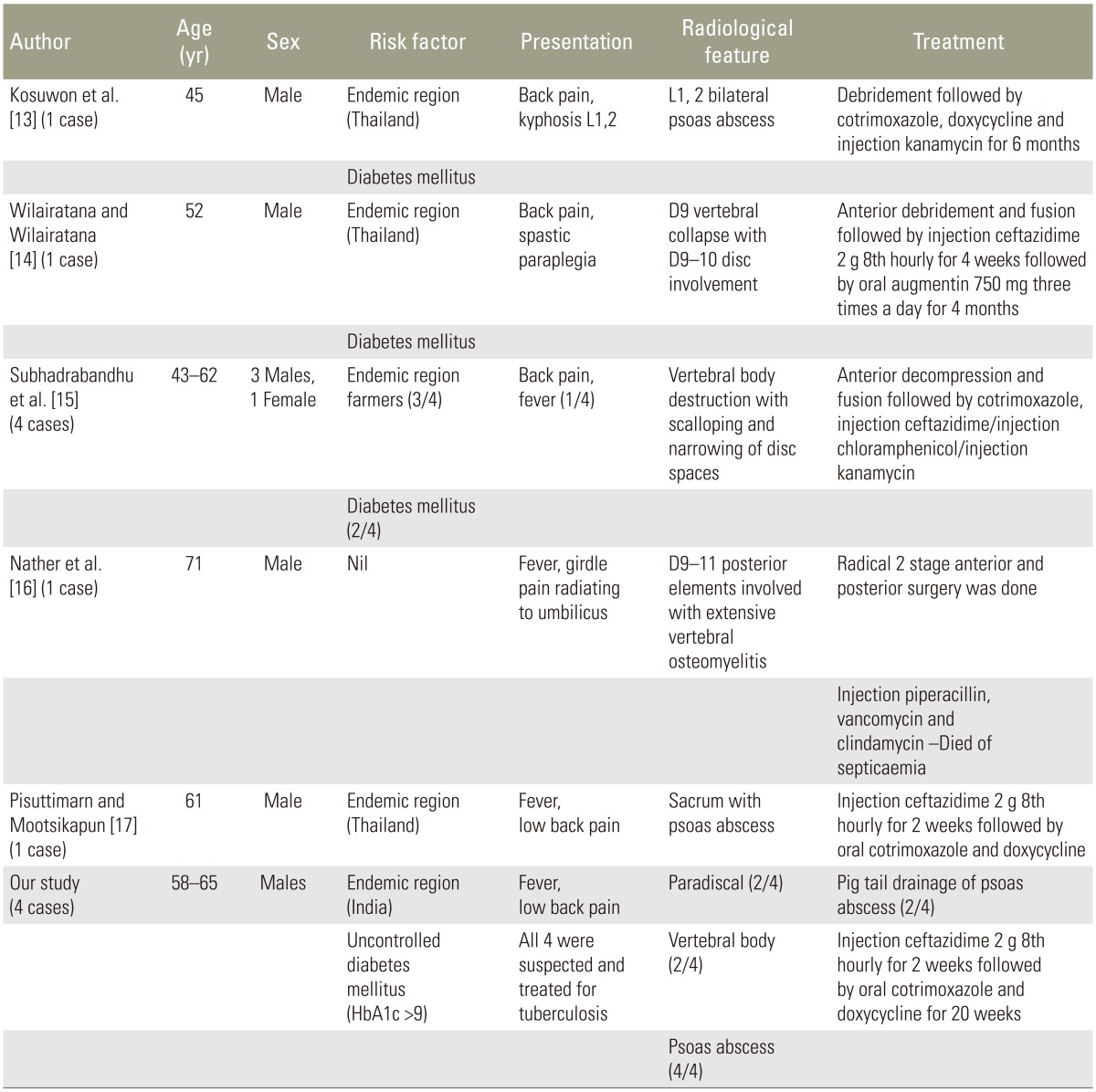

Melioidosis has already been termed as the “remarkable imitator” [11] and “mimicker of maladies” [12]. Melioidotic spondylitis is a fairly uncommon, chronic condition and hence poses a special challenge in terms of both diagnosis and treatment. In developing countries, as the incidence of tuberculosis is high, virtually all patients with spondylitis with abscess, discharging sinuses, and elevated ESR and CRP levels are treated along the therapeutic guidelines of tubercular spondylodiscitis. Growth of the bacterium in culture media always remains the “gold standard” method of diagnosis in case of infective spondylitis. Lack of awareness, inadequate laboratory facilities, and high prevalence of tuberculosis are the main reasons for underdiagnosis of melioidotic spondylitis. Table 3 shows a comparative summary of our clinical analysis and data reported in the literature [1314151617].

Conclusions

Melioidotic spondylitis presents with a clinical picture similar to that of tuberculosis, with fever and back pain being the main complaints. Tissue biopsy shows non-caseating granulomas, and bacteriological studies are performed to confirm the disease, which is treatable with appropriate antibiotic therapy.

In regions where tuberculosis is prevalent, melioidotic spondylitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who do not respond to empirical anti-tubercular treatment. This is of particular importance in patients with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with suspected infective spondylits.

We advise that healthcare workers and all treating physicians, particularly orthopedic and spinal surgeons, maintain a high index of clinical suspicion in light of the increasing incidence of this potentially fatal disease.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.