Spinal Epidural Abscess with Pyogenic Arthritis of Facet Joint Treated with Antibiotic-Bone Cement Beads - A Case Report -

Article information

Abstract

Most epidural abscesses are a secondary lesion of pyogenic spondylodiscitis. An epidural abscess associated with pyogenic arthritis of the facet joint is quite rare. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of the use of antibiotic-cement beads in the surgical treatment of an epidural abscess. This paper reports a 63-year-old male who sustained a 1-week history of radiating pain to both lower extremities combined with lower back pain. MRI revealed space-occupying lesions, which were located in both sides of the anterior epidural space of L4, and CT scans showed irregular widening and bony erosion of the facet joints of L4-5. A staphylococcal infection was identified after a posterior decompression and an open drainage. Antibiotic- bone cement beads were used as a local controller of the infection and as a spacer or an indicator for the second operation. An intravenous injection of anti-staphylococcal antibiotics resolved the back pain and radicular pain and normalized the laboratory findings. We point out not only the association of an epidural abscess with facet joint infection, but also the possible indication of antibiotic-bone cement beads in the treatment of epidural abscesses.

Introduction

An epidural abscess is an uncommon disease that may cause an irreversible paralysis or death. Pyogenic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint is quite a rare cause of lower back pain. Fewer than ten cases of epidural abscesses associated with pyogenic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint were reported in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of the use of antibiotic-cement beads in the surgical treatment of an epidural abscess. This report presents an epidural abscess complicated with pyogenic arthritis of a lumbar facet joint as an unusual cause of back pain and the use of antibiotic-cement beads as a possible supplement to the surgical treatment of this condition.

Case Report

A 63-year-old male was transferred from a local clinic, complaining of radiating pain to both lower extremities lasting for one week. The tender points were found on the midline of back and both paravertebral muscles, but body temperature was normal. The range of motion of his spine was severely limited, and there was a decrease of the straight leg raising tests (60/60). The motor powers of the extensor hallucis longus were decreased bilaterally and ankle jerks were absent bilaterally. He denied the history of acupuncture or local injections in the back.

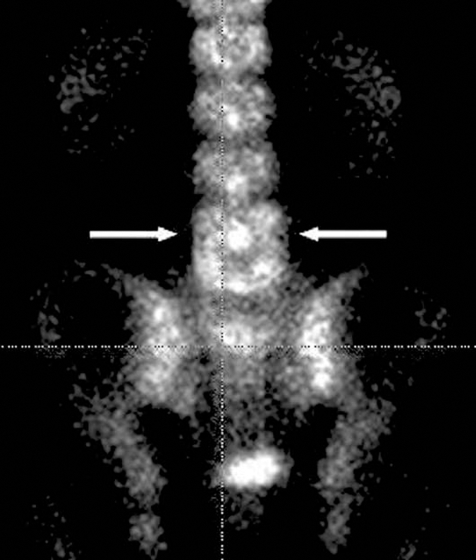

Initial investigations revealed that the white blood cell count was 9,300/mL, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 118 mm/hr and C-reactive protein was 12.5 mg/dL. Serum GOT/GPT levels were 59/87 IU/L, but the sonogram of the liver was normal. The electromyography and nerve conduction study revealed radiculopathies of L5 and S1, bilaterally. Plain radiographs of the L-spine showed no specific abnormality. MRI revealed two space-occupying lesions, which were located on both sides of the anterior epidural space, and a signal change of the dural sac at the level of L4 and L5 (Fig. 1). Computed tomography (CT) axial scans revealed the same space-occupying lesion, adhesion and thickening of the roots of L4 and L5, and showed irregular widening and bony erosion of the facet joints of L4-5 (Fig. 2). Technetium-99 m bone scan demonstrated increased uptake at the L4 and L5 levels (Fig. 3).

Axial T2-weighted MRI reveals two space-occupying lesions, which are located on both sides of the anterior epidural space (arrows), and a signal change of the dural sac at the level of L4 and L5.

Axial CT reveals a space-occupying lesion on anterior epidural space, adhesion and thickening of the roots of L4 and L5, and irregular widening and bony erosion of the facet joints of L4-5 (arrows).

Technetium-99 m bone scan shows increased uptake of radioisotopes on the bodies and posterior arches of L4 and L5 (arrows).

On the 4th day of admission, he had chills with temperatures to 38.9℃ with increasing back and radicular pain. The white blood cell count was 11,200/mL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 123 mm/hr and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 14.1 mg/dL. We decided on surgical decompression after parenteral antibiotics (first generation cephalosporin & aminoglycoside) for 2 days.

Under a general endotracheal anesthesia, a total laminectomy and bilateral medial facetectomies of L4 and partial laminectomies of L3 and L5 were performed. In the surgical field, the L4-5 facet joints were destroyed and the drained pus from the facet joints was located on both sides of the anterior epidural space. A severe adhesion between the dura and the annulus fibrosis, and a thickening and adhesion of the L4 and L5 roots were also noted. A histological examination from frozen biopsy revealed an inflammation. The drainage of the pus and the removal of the inflamed granulation tissues and surrounding fibrous tissues were performed. In fear of incomplete removal of the infected tissues and for local control of the infection, we decided to use antibiotic-cement beads. Vancomycin 4 gm and bone cement 40 gm were mixed, and 7 rows of beads were inserted on the posterior aspect of L3 to S1 (Fig. 4). We planned the fusion with or without instrumentation after removal of the antibiotic-cement beads two weeks later. The radiating pain was immediately relieved after the operation. First generation cephalosporin and aminoglycoside were administered intravenously for two weeks. The blood and intraoperative pus cultures demonstrated methycillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Postoperative plain radiograph shows posterior decompression and antibiotic-bone cement beads in posterior aspect of the spine.

During the second surgery, some pus that was admixed with chocolate colored liquid material was noted, so we abandoned the use of instrumentation. A posterolateral fusion with autogenous iliac bone at the level of L3 to L5 was performed. Second generation cephalosporin and quinolon were then administered intravenously for 3 weeks. Oral quinolon was then prescribed for four weeks until the ESR was normal. The patient was on bed rest postoperative for 3 weeks, and then was ambulated with thoracolumbosacral orthosis for 3 months. At three-months after surgery, solid fusion was achieved (Fig. 5). And at 2 years follow-up, the patient returned to normal physical activity without low back pain.

Discussion

Epidural abscesses are usually a complication of pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Several reports of pyogenic arthritis of lumbar facet joints have been reported1-5. Fewer than 10 cases of epidural abscesses associated with pyogenic arthritis of the facet joints have been reported6-9. Epidural abscess formation was complicated in 25% of pyogenic facet joint infections and 38% of the complicated cases developed severe neurologic deficit8. In our case, the patient with radiculopathy had resolution of radicular symptom after surgery.

As in our case, WBC count was elevated approximately 50% of the time, and ESR and CRP were uniformly elevated. Staphylococcus aureus was the most common organism, accounting for 80% of reported cases8.

Evidence of a septic facet joint infection or, an epidural abscess on plain radiographs, in the form of bony changes consistent with osteomyelitis, is not visible for 2~3 weeks post onset1. A technetium-99 m bone scan is 100% sensitive in detecting facet joint infection as early as 3 days after symptom onset6. But gallium scans or indium 111-labeled leukocyte scans are more specific than technetium scans in differentiating infection from other diseases. CT can be used to localize the infection and to visualize bone and soft tissue involvement6. MRI is the imaging modality of choice in its earliest stages and in delineating the extent of soft tissue involvement, including abscess formation8.

An epidural abscess without neurologic deficit can be treated with percutaneous drainage and parenteral antibiotics, but an epidural abscess with severe neurologic deficit is a surgical emergency and should be treated with direct decompression of the epidural space.

Antibiotic impregnated bone cement has been introduced in the prevention or the treatment of infected artificial joints and infected long bones10. We used antibiotic-bone cement beads for the treatment of spinal epidural abscesses as a local controller of the infection and as a spacer or an indicator for the secondary fusion operation.

Until now, the use of antibiotic-bone cement beads in the treatment of epidural abscesses has not been established, but we hope this modality to be beneficial in the treatment of various spinal infections.