Lumbar Spinal Stenosis: Review Update 2022

Article information

Abstract

Patients with lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) may experience neuropathic symptoms, such as back pain, radiating pain, and neurogenic claudication. Although the long-term outcomes of both nonsurgical and surgical treatments are similar, surgery may provide shortterm benefits, including improved symptoms and lower risk of falling. Decompression is mainly used for surgical treatment, and depending on the decompression degree and associated instability, combination therapy may be given. Minimally invasive surgery has been demonstrated to produce excellent results in the treatment of LSS. Thus, an approach aimed at understanding the overall pathophysiology and treatment methods of LSS is expected to have a better therapeutic effect.

Introduction

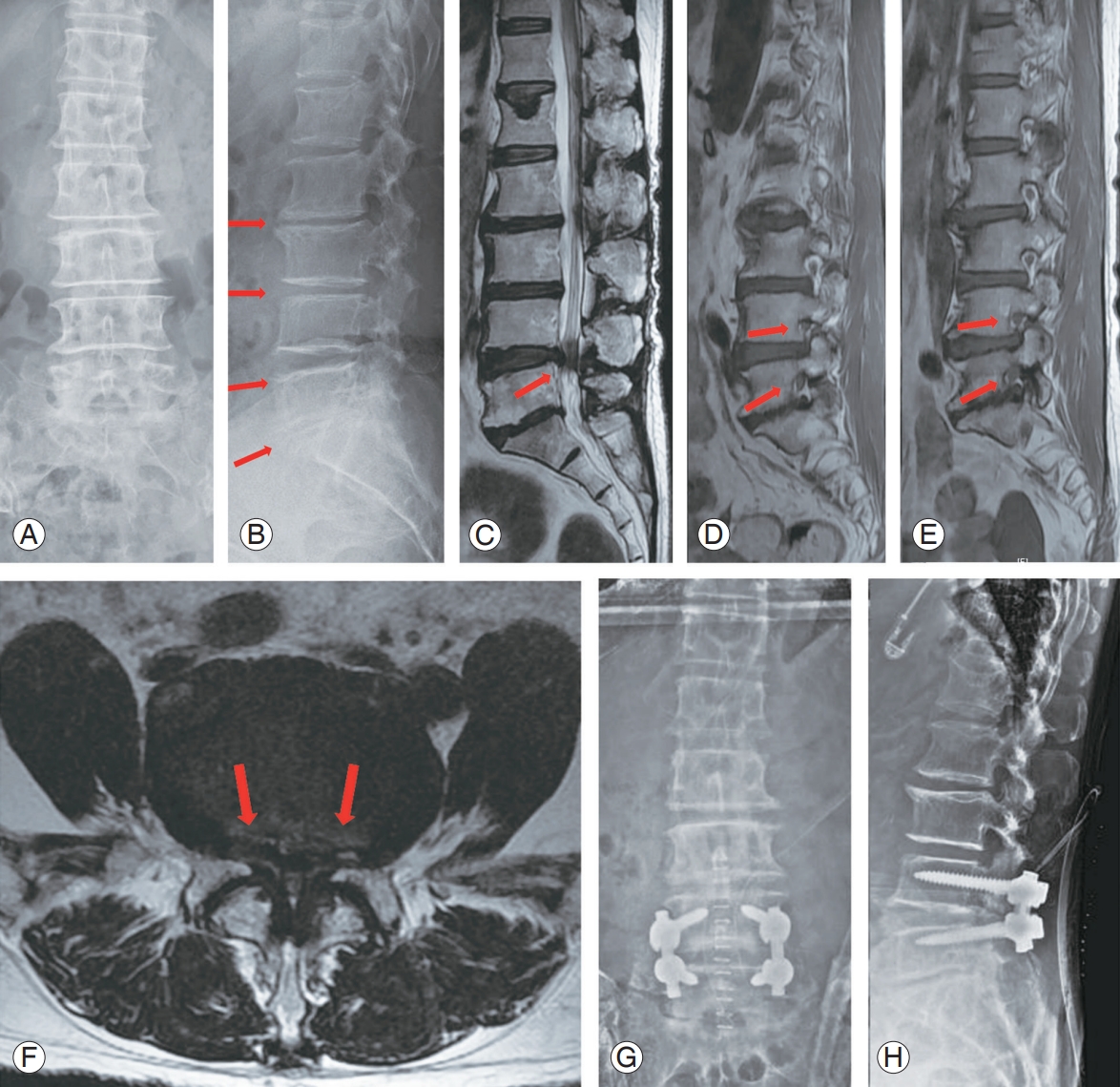

Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is the narrowing of the spinal canal caused by degenerative changes in the vertebral joints, intervertebral discs, and ligaments, particularly the ligamentum flavum. As the area around the neurovascular tissue becomes smaller, the following significant clinical symptoms could occur: neurogenic claudication, radiating pain in the lower extremities, back discomfort, urinary and defecation issues, and extras [1-3]. Clinical signs include weariness, increased discomfort in the lower limbs, and diminished sensation in the lower extremities. The pain in the lower extremities may worsen with extended standing or walking (neurotic intermittent claudication) [3,4]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that improved radiological diagnosis and treatment modalities, including minimally invasive surgical methods, such as endoscopic surgery, can enhance the diagnosis and surgical results of patients with LSS (Table 1) [3,5].

Pathophysiology and Treatment Principle

Degenerative LSS is a progressive disease that affects all mobile segments of the spine [6], which may result in intervertebral disc degeneration, instability caused by facet joint hypertrophy and distortion, calcification or thickening of the plate ligament, spinal stenosis, and nerve structure compression. The increased vascular pressure may cause occasional neurogenic claudication and epidural venous congestion. The diffusion of cerebrospinal fluid and blood flow in the arteries on the surface of the neuromuscular give it metabolic energy. The increased metabolic rate of the nerve root cannot be treated when the spinal canal stenosis compresses the nerve root, leading to nerve ischemia and conduction disruption. Most of the time, symptoms are caused by congestion in a vein with two or more stenoses. If the nerve root is injured by the continuous compression of the stenotic structure, central hypersensitivity of pain perception may occur, which could lead to persistent pain even after the surgical removal of the stenotic structure [3].

Anatomy

Due to the overlapping and looseness of the yellow ligaments caused by the reduction in disk height, degenerative LSS may result in instability and spinal stenosis. This relative hypermobility may cause the facet joint and encircling ligaments to enlarge and thicken. Central stenosis is the narrowing of the area between the two posterior faces, which is mostly occupied by the dural sac and internal nerve systems. The main contributors to the stenosis in this region are intervertebral disc protrusions, annulus fibrosus protrusions, osteophytes, and folded or thickened yellow ligaments. Symptomatic central stenosis leads to excruciating neurogenic claudication of the lower limbs. Radiating pain can be caused by compression of the nerve root, which exits the dural sac through the lateral canal. The medial border of the articular process to the medial border of the pedicle defines the lateral concavity, commonly referred to as the “entrance zone” [6]. The distal and lateral sections of this region are where the nerve roots of the dural sac flow. The lateral concavity is bounded medially by the spinal canal, anteriorly by the intervertebral disc and posterior ligament, dorsally by the superior articular process of the facet joint, and laterally by the pedicle. The main causes of entrance stenosis are herniation of the posterior disk and hypertrophic osteoarthritis of the posterior joint, which compress the nerve root through the enlarged upper articular process. The midzone refers to the area of the hole in front of the wave [7]. The anatomy matches the ventral portion of the pars. The pedicle surface externally, the pars and intertransverse ligaments posteriorly, the vertebral body and intervertebral discs anteriorly, and the lateral concave medially are all bordered by them. Compression by the osteophytes or thickening of the fibrocartilage tissue in the vicinity of the wave defect cause stenosis in this region. The neural foramen is the space between the bottom half of the upper pedicle and upper part of the lower pedicle, and the intervertebral foramen is the shape of an inverted teardrop facing backward. In addition to being on the posterior aspect of the vertebral body and posterior aspect of the intervertebral discs, it is located in front of the lower vertebrae [6]. The ventral motor root and dorsal root ganglion both occupy around 30% of this area. The epineurium, which wraps around the nerve roots of the dura, forms in this region. This region contains nerve roots that may be squeezed by arthritis, spondylolisthesis-related subluxation, or distal disk protrusion [8]. The degenerative process of the ligamentum flavum and vertebral body joints is the primary cause of LSS, and imaging shows the progression of spondyloarthropathy [9]. Typically bilateral, these aberrant findings are most frequently observed between L4 and L5, then between L5 and the sacrum, and lastly between L3 and L4.

Natural History

LSS without symptoms is typical. According to several researches, there is no correlation between clinical complaints and the anteroposterior spinal canal diameter. Most of the time, LSS gradually develops over time, but occasionally, it becomes severe as a result of trauma or intense exercise. After 8–10 years of follow-up, 50% of patients who underwent nonsurgical treatment reported reduced back and leg pain, although several studies have demonstrated that surgically treated patients had better outcomes. Regardless of the type of treatment, symptoms improved after around 3 months and in some cases after 12 months in a prospective, randomized analysis of 100 patients with stenotic symptoms who received surgical or nonsurgical treatment. The symptoms became better. In the nonsurgical treatment group, the symptoms worsened with time, but after 4 years, almost half of the patients had made excellent or significant progress. About 80% of individuals who underwent surgical treatment had successful outcomes [10]. According to a different study, most people with LSS had steady disease progression, and 15%–50% of those who underwent nonsurgical treatment had successful results [11]. If symptoms worsen after proper conservative treatment, surgery might be advised. According to Weinstein et al. [10], the surgical treatment group outperformed the nonsurgical treatment group on all significant outcomes.

Prevalence

As was already established, there are differences in the overall prevalence. The clinical diagnostic criteria estimated the prevalence to be between 11% and 38% in the general population and asymptomatic individuals [12-14]. The prevalence increases with age, and it is known that imaging tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), can detect cancer 10 years earlier than clinical symptoms alone. The prevalence ranged from 7% to 23% in some studies that used the International Classification of Diseases codes. In subjects aged 67 years (range, 40–93 years), the prevalence was approximately 78% compared with approximately 12% in patients aged 40 years [7]. It was previously thought to be more common in men, but it is now known to occur 3–5 times more frequently in women [8,15].

Clinical Evaluation

An expert consensus on clinical symptoms, according to a 2016 study, comprises (1) leg or buttock discomfort while walking, (2) symptom relief when leaning forward, (3) back pain while using, includes bending forward to relieve symptoms, (4) motor or sensory issues while walking, (5) a normal and symmetric dorsalis pedis pulse, (6) weakness of the lower limbs, and (7) low back pain [9,16]. Other studies used a thorough medical history, gait, and a few physical examination findings as categorization criteria [16-18]. In addition to preexisting spinal stenosis, sudden onset or aggravation of sciatica may indicate disk herniation. The most frequent neurological manifestation of radiation pain is L5, which is common with lateral access and foraminal stenosis [12]. A neurological examination may detect movement abnormalities as a result of L5 nerve root compression caused by severe stenosis or degenerative spondylolisthesis. Peripheral neuropathy caused by diabetes, alcoholism, or drug use should be suspected when there is paresthesia. To identify blood flow obstructions and rule out lower-extremity edema and varicose veins, the dorsum of the foot and popliteal artery should be palpated [19]. Furthermore, it should be separated from signs of lesions in the lower extremities, such as hip and knee lesions [3,20-24]. Some provocative tests, such as the walking, fall-related, and handgrip strength tests, can also be employed to assess the current and postoperative status of patients with LSS [25-30]. The Oswestry Disability Index score and the intensity of the patients’ leg discomfort were likewise connected to the neuropathic pain component [31].

Diagnosis Imaging

1. Radiography

Although a simple radiographic examination cannot confirm stenosis, the short pedicle observed in lateral radiographs, narrow distance between the pedicles observed in the anterior and posterior radiographs, calcified ligaments or intervertebral discs, stenosis of the foramen, and hypertrophy of the facet joint can all be seen. The presence or absence of segmental instability on the flexion–extension lateral image can be used to determine the necessity of fusion. In a dymamogram, a translational motion of more than 4–5 mm or an angular change of more than 10°–15° indicates segmental instability [8,31].

2. Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI can be used to detect LSS and measure the size of the spinal canal and the degree of degenerative changes [1,23,32-35]. It should be emphasized that the correlation between the severity of morphologically stenotic lesions on an MRI and clinical symptoms is small. In other words, the intensity of clinical symptoms is not directly correlated with the degree of stenosis detected by MRI [32]. Although MRI confirms strictures in a large percentage of asymptomatic patients, it should not be employed for screening. MRI can be used to confirm the diagnosis in patients with persistent neurogenic claudication or radiating pain. A sagittal T1-weighted scan clearly shows the foraminal stenosis, whereas a sagittal T2-weighted image resembles a myelogram [36]. When the fatty tissue that is typically dispersed around the nerve root is absent, foraminal stenosis can be identified. The central stenosis is clearly visible in both the T2- and T1-weighted pictures of the axial cut image. When the adipose tissue that usually covers the disk and nerve root is absent, axial slices on T1-weighted images show a distant lateral disk herniation. Recently, it has been found that LSS may be quantified using intraspinal diffusion tensor imaging metrics as apparent diffusion coefficient and fractional anisotropy [5].

3. Computed tomographic myelography

CT images are frequently used for surgery planning in patients with stenosis [37]. Patients with dynamic strictures, postoperative leg discomfort, severe scoliosis or spondylolisthesis, metal implants contraindicating MRI scans, and lower-extremity complaints without aberrant results on MRI scans should also undergo a CT scan in addition to the imaging test. Myelography is the most suitable term. Myelography, however, is an intrusive procedure that increases the risk of headaches, nausea, and seizures. Standing in flexion and extension while having restricted sight on the MRI is required for this test, which records moving pictures from the lateral side [20,33]. In addition, CT can actually provide the information required for decompression surgery because it offers more information about bone architecture, such as osteophytes and disk calcifications, than MRI [35]. Patients with pacemakers who are unable to undergo MRI diagnostic examinations have a great alternative imaging option in CT scan.

4. Other diagnostic studies

Electromyography can be employed in patients with concomitant conditions such as diabetes if the diagnosis of neuropathy is ambiguous [33]. Furthermore, lesions caused by vascular issues in the lower extremities can be ruled out using vascular Doppler imaging. The Bicycle and Bruce technique may be diagnostic, according to one study [33,38].

Nonoperative Treatment

Treatment options other than surgery are advantageous for patients with mild to severe symptoms. Treatments for lumbar spinal pain include resting for about a week, antiinflammatory medications, oral corticosteroids, muscle relaxants, prostaglandin E1 analogs, antidepressants, anticonvulsants (gabapentinoids), physical therapy, wearing of braces, heat therapy, ultrasound, massage, electrical stimulation, and traction [39,40].

1. Epidural steroid injection and others

An intermediate type of treatment between nonsurgical options and epidural steroid injections. According to several studies, between 50% and 87% of patients have short-term (around 3 weeks) symptom alleviation using epidural steroid injection therapy [2,19,41-44]. Epidural steroid injection is indicated for acute radiating pain and nervous claudication that are interfering with daily life despite pain relievers and rest, which are expected to improve symptoms [45]. In addition, research on the use of ropivacaine and dexmedetomidine as well as epidural neuroplasty in conjunction with thoracolumbar surgery has been recently published [46,47]. Epidural neuroplasty is employed to alleviate back discomfort and/or radiating pain caused by mechanical compression of the intravertebral nerve structures or neuroinflammation. Epidural neuroplasty/epidural glue separation has recently gained popularity and has produced encouraging outcomes. Epidural abscesses, irreparable nerve tissue destruction, and cardiovascular events have all been recorded as fatal consequences [24].

2. Principles of spinal stenosis surgery

After receiving appropriate conservative treatment for at least 2–3 months, surgery is recommended when patients complain of pain, muscle weakness, and gait disturbance caused by lower-extremity paresthesia, which affect their daily life. Surgery is rarely used to treat low back pain caused by spondylolisthesis and scoliosis when there is no instability [48]. It is difficult to predict the likelihood of recovery after surgery, even when uncommon long-term motor paralysis is the main symptom; thus, other causes should be identified prior to surgery. Rapidly developing neurological abnormalities or the lack of urine and feces necessitate early decompression [11,21,46]. When deciding whether to undergo surgery, abnormal findings on CT or MRI imaging should correlate to the patient’s complaints [22]. The principle of surgical treatment is to sufficiently decompress the nervous structures [11]. If instability due to the removal of too many bone structures following adequate decompression is anticipated, immobilization should be considered. Candidates for fusion surgery may also include those who have severe stenotic lesions and spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or kyphosis [49]. Other fusion requirements include disk herniation following prior surgery, recurring stricture, and proximal segmental degeneration caused by prior fusion. In older individuals with severe multisegmental stenosis, laminectomy alone may be recommended (Figs. 1–3) [3]. Less than 50% of the inner section of each facet of one spinal segment must be removed during decompression to provide appropriate decompression without resulting in segmental instability [3]. More localized decompression is possible by identifying the exact cause of symptoms with selective nerve root blocks. Checking for neural membrane adhesions, which may be present even in the absence of a history of surgery, during decompression can help limit the risk of dural damage [50]. If the stenosis of the lateral depression and neural foramen is severe, the surgical instruments used during decompression may cause nerve damage [51,52]. The sagittal plane must be adjusted for fusion surgery to be successful, and even elderly patients aged over 65 and very senior patients aged over 80 can have successful operations provided the sagittal plane is balanced thereafter. Gained is decrease the chance of falls following surgery [28,29,53,54]. Recently, single- or biport endoscopic surgery and minimally invasive screw insertion techniques guided by fluoroscopy or a navigation system have emerged. With the rapid advancements in surgical techniques and technology, there is a growing trend toward the use of spine endoscopy. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that endoscopic and standard minimally invasive or open techniques produce comparable patient-reported outcomes [50,55,56]. No difference was observed in patient-reported outcomes between a number of additional randomized controlled trials contrasting endoscopic discectomy and laminectomy with conventional procedures, such as microsurgical laminectomy, microdiscectomy, or open discectomy [56]. Similar to arthroscopy employed in knee and shoulder surgery, biportal endoscopy contains two working channels, one for the endoscope and one for the instruments. For the lumbar spine, the posterolateral (or intervertebral) approach and the extraforaminal route (or transforaminal) are the two most often used endoscopic surgical procedures [55,56-58]. Despite the development of numerous novel techniques for lumbar disk herniation treatment, open microdiscectomy and laminotomy/laminectomy remain the current standard of care [8,50]. Global trends in spinal endoscopy utilization, on the other hand, indicate that Asia has the highest utilization and growth. According to a recent global survey, 55% of non-Asian surgeons and 70% of Asian surgeons perform spinal endoscopy [59]. These obstacles must be removed to allow broader access to the entire spine community as the body of scientific literature supporting this treatment grows and its application becomes more advanced and widespread in Asia.

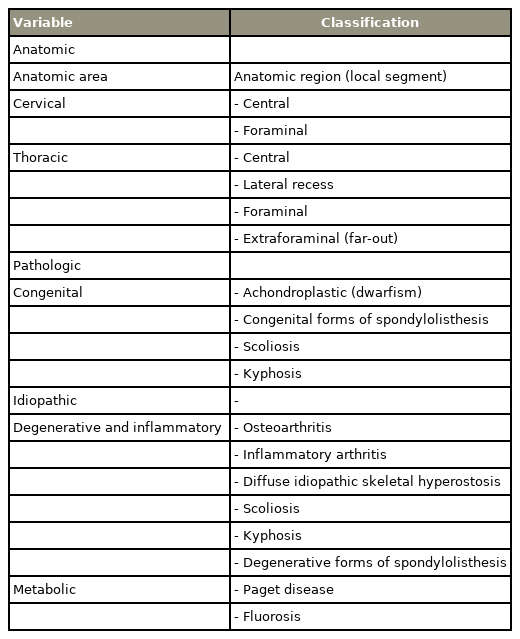

Pre- and postoperative X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging image in 60-year-old female patient with spinal stenosis. She underwent surgical decompressive surgery due to refractory back and both lower leg radiating pain in spite of 4 months of conservative treatments. (A–D) Spinous process preserving decompressive surgery was done under microscope. (E–H) In the preoperative sagittal and axial image scan, central stenosis and both lateral recess stenosis are seen. Postoperatively, adequate amount of decompression on the stenotic region could be seen.

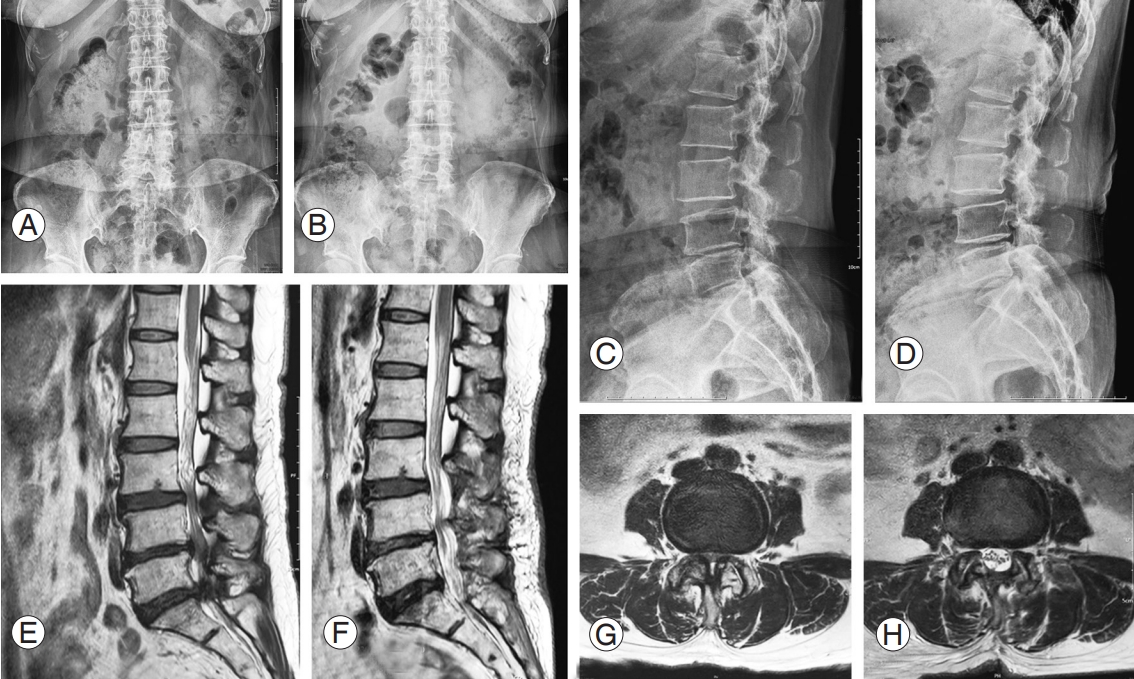

Preoperative (Preop) and postoperative (Postop) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) image in 50-year-old female patient with spinal stenosis. She underwent surgical decompressive surgery due to refractory back and both lower leg radiating pain in spite of 6 months of conservative treatments. (A–F) In the sagittal and axial image scan, central stenosis and both lateral recess stenosis are seen. Postoperatively, the stenotic lesions were resolved. (G–I) Intraoperative imaging of 0-degree endoscope. The spinal stenosis lesion is well decompressed with biportal endoscopic spine surgery technique. The expansion of dural sac and enough space of dural sac lateral margin were confirmed (yellow arrow). Also, both traversing roots with blunt root hook or dura dissector were found to be redundant after decompression. POD, postoperative day.

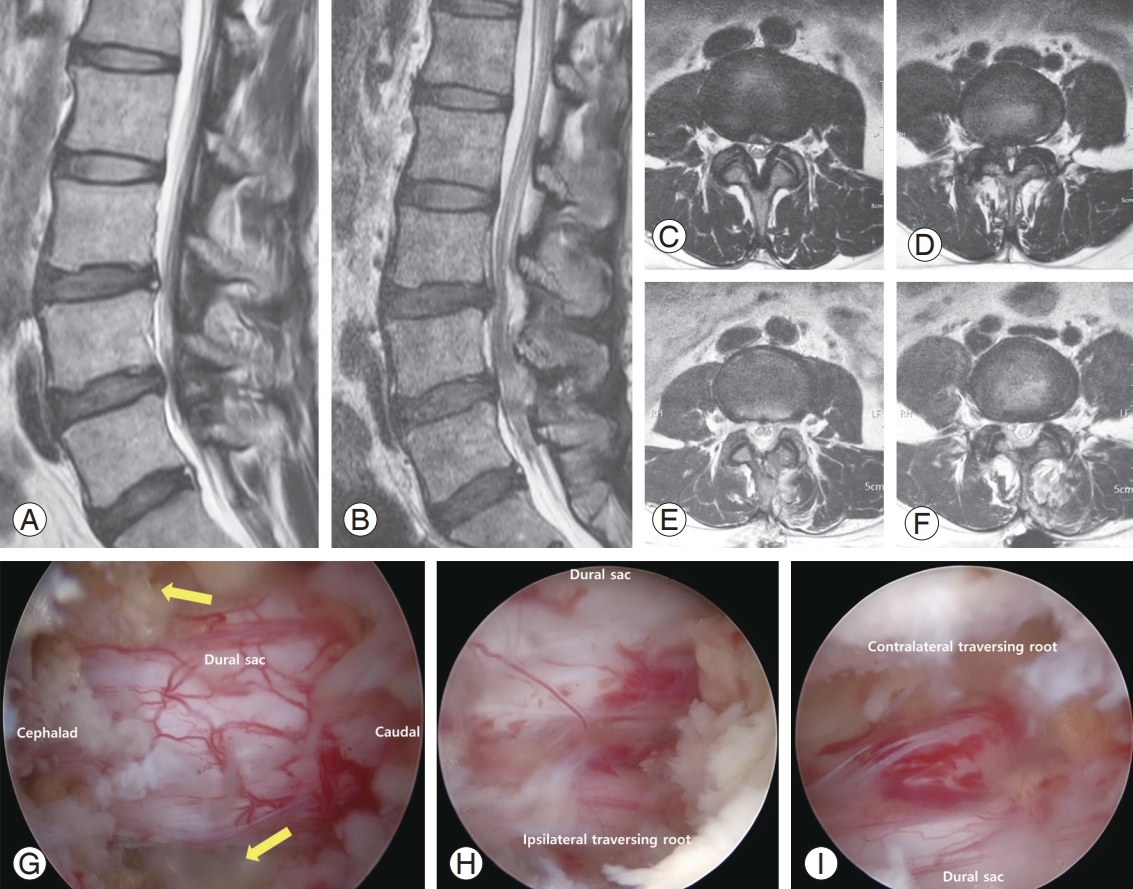

Pre- and postoperative X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging image of 69-year-old female patient with spinal stenosis. She underwent surgical decompressive surgery and posterolateral fusion due to refractory back pain, both lower leg radiating pain and neurogenic intermittent claudication in spite of 6 months of conservative treatments. (A, B) Disc height narrowing throughout L2 to S1 can be observed (arrows). (C–F) Severe L4–5 central and both lateral recess stenosis and mild to moderate degree of foraminal stenosis of both L4–5–S1 is observed on magnetic resonance image (arrows). (G–H) Decompression and posterolateral fusion with instrumentation between L4–5 were done.

Conclusions

Neurogenic claudication, radiating pain, and back pain are all signs of LSS. Nonsurgical and surgical treatment outcomes were found to be comparable over the long term; however, surgery has advantages, such as temporary relief in symptoms and a lower risk of falling. Decompression is the main goal of surgical therapy, with fixation surgery as a secondary option depending on the degree of decompression, concomitant instability, and structural issues. Recent studies have demonstrated that less-invasive surgery is superior for treating LSS. As a result, a strategy centered on comprehending the full pathogenesis of LSS and treating it offers greater therapeutic results.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: JWK, SHM, BHL; acquisition of data: JWK, SYP, SJP; analysis and interpretation of data: JWK, BHL, SRP; drafting of the manuscript: JWK, BHL; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JWK, BHL, SKS, HSK; study supervision: HSK, SKS.