Ten Important Tips in Treating a Patient with Lumbar Disc Herniation

Article information

Abstract

Lumbar disc herniation is a common spinal disorder that usually responds favorably to conservative treatment. In a small percentage of the patients, surgical decompression is necessary. Even though lumbar discectomy constitutes the most common and easiest spine surgery globally, adverse or even catastrophic events can occur. Appropriate patient selection and effective neural decompression constitute the most important points for better surgical outcomes and avoidance of unpleasant complications. Other important tips include timely performance of magnetic resonance imaging, correct interpretation of scan data, preoperative detection of underlying instability, exclusion of non-discogenic sciatica, determination of the main cause of clinical pathology, avoidance of the wrong side or level, and being sure that the more detailed procedure does not necessarily mean the more effective procedure.

Introduction

Symptomatic lumbar disc herniation (LDH) is a common spinal disease affecting 1%–3% of general population, but only 15%–20% of these cases require operative intervention [1]. Lumbar discectomy is the most common and straightforward spinal operation, yet it is fraught with potentially serious complications [2]. Thus, it has a reputation of simultaneously being the easiest and most difficult surgery.

The spinal column is a complex entity and comprised of numerous blood vessels, nerve fibers, ligaments, muscles, joint, vertebrae, and intervertebral discs. Before any intervention, the cause and effect relationship between the pathologic and clinical findings should be demonstrated. Here, we highlight top ten key points should not be forgotten in approaching these peculiar patients.

Use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Lumbar spine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not necessary in all patients with low back pain (LBP). Most authors propose conservative treatment at the beginning of the disease. In about 30% of the asymptomatic and otherwise normal persons, some abnormalities may be detected by MRI [1]. Vertebral hemangioma is a spinal tumor that occurs in 10%–27% of the general population, with intervention not usually being needed [3]. Degenerative disc disease is a frequent imaging. The disease begins from the second decade of life and its incidence and severity increases thereafter, although in most of the affected cases a direct relationship with LBP cannot be verified [4]. Lumbar spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are other common paraclinical findings in adults that can be seen frequently on routine lumbosacral radiographs; they are often asymptomatic or effectively respond to nonoperative treatment [5]. Lumbosacral transitional vertebra (lumbarization and sacralization) is another finding that has no direct relationship with LBP, although a causal link exists between the transitional vertebra and the degeneration of the disc immediately above it [6]. Other incidental findings include Tarlov cyst, fibrolipoma, synovial cyst, and sacral meningocele [7]. Tarlov cyst is a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-filled cyst formed within the nerve root sheath in the spinal canal of the sacral region. These cysts are usually asymptomatic but enlarged cysts can compress the adjacent nerve fibers and create pain, weakness, and paresthesis [8].

In the patients with acute LDH who present with sciatica, positive straight leg rising (SLR), or some paresthesis on the leg without significant neurologic and sphincter disturbances, the early ordering of a MRI scan has a strong iatrogenic effect and may unintentionally increase a patient's anxiety increase and may trigger the use of some unnecessary invasive procedures [910]. The humorous state that occasionally seen in the scientific literature indicates that for obtaining more patients to operate, more MRI scanning should be ordered [10].

Underlying Instability Should be Detected Preoperatively

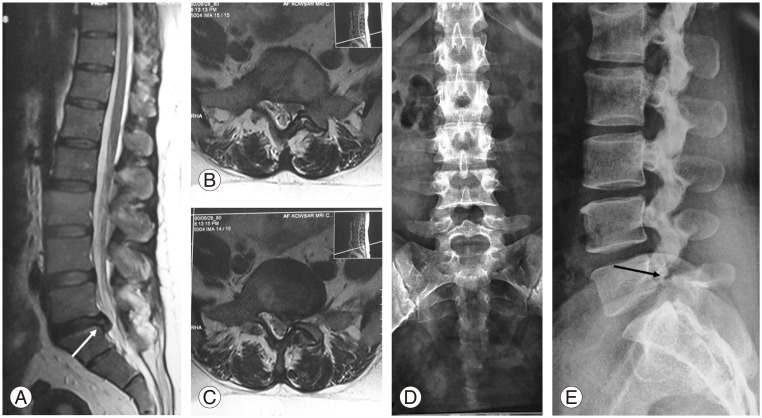

Simple discectomy, even with minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS), if done with careless disregard of underlying instability, can lead to worsening of the patient [11]. In those ambiguous situations if which clinical and MRI findings are inconsistent, lumbar spondylolysis should certainly be ruled out. Classically, LDH compresses the lower or traversing nerve root, while symptomatic spondylolysis with its proliferative fibrosis at the region of pars interarticularis usually compresses the upper or exiting nerve root (Fig. 1). However, one should remember that, similar to spondylolysis, in patients with far lateral LDH the upper nerve root is clinically affected and may confuse the clinical picture [12].

A 26-year-old female presented with chronic low back pain and left sciatica. Her ability to walk was significantly decreased. Physical examination revealed positive straight leg rising and weak big toe extension force on the left, while Achilles tendon reflex was completely normal. We clinically expected to see a L4–L5 lumbar disc herniation (LDH) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (A–C) Sagittal and axial MRI scans show L5–S1 LDH (white arrow) that contradicted the clinical picture. (D, E) Plain radiographies detect L5 spondylolysis (black arrow).

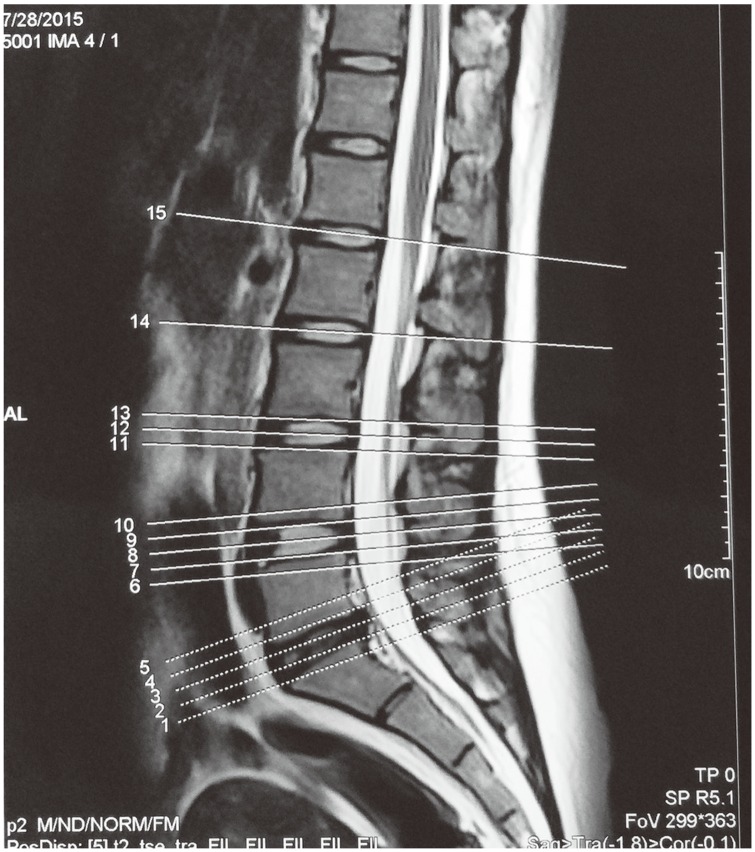

Usual axial MRI scanning with cursors placed through the intervertebral spaces leave large intervening skipped areas or gaps. Pars interarticularis defect (spondylolysis), migrated sequestrated disc, conjoined nerve roots, facets, neuroforamen, lateral recesses, and intraspinal synovial cysts may be easily missed on axial MRI (Fig. 2). The correct method for axial image cutting should be contiguous from the midbody of L3 to the midbody of S1, and it is not necessary to be exactly parallel to the intervertebral discs [13].

An incorrect method for axial image cutting. There are skipped areas between the intended cuts. Sequestrated discs behind the vertebral bodies or defect in pars interarticularis (spondylolysis) may be easily missed.

Another important issue is the change in vertebral slippage or alignment between standing and lying positions. As a rule, supine spinal radiography is more appropriate for visualization of anatomical details, while standing spinal radiography is more suitable for detecting instability or deformity (including scoliosis and kyphosis). Vertebral slippage can be decrease up to 26% as the patient reclines from the upright position [14]. Therefore, lumbar spondylolisthesis can be overlooked in routine supine MRI. In surgical planning for patients with LDH, plain standing anteroposterior and lateral lumbosacral radiographs should be taken. In suspicious cases, oblique views of the lumbosacral spine may be helpful, although computed tomography (CT) or bone scan may be necessary to detect a pars lesion [15].

Non-Discogenic Sciatica Should be Ruled Out

Although sciatica may be due to LDH in 90% of cases, non-discogenic reasons should also be considered [16]. Any compressive or inflammatory lesions along the course of lumbosacral roots or sciatic nerve may cause leg pain. A solitary osteochondroma of the ischial ramus, lumbar nerve root schwannoma, facet hypertrophy, ankylosing spondylitis, sacroiliitis, sciatic neuritis, intrapelvic mass, pelvic endometriosis, piriformis syndrome, and herpes zoster infection are some examples causing radicular pain in lower extremity mimicking LDH [16].

Make Sure That the Offender is the Main Culprit

In evaluating a particular pathology, it is important to remember that not every complaint may be relevant. Degenerative disc disease is common and is reported in nearly three-quarters of adults. So, degenerative disl disease alone is not an appropriate indication for lumbar surgery [17]. A comprehensive history and physical examination with especial attention to a simultaneous pathology in cervical or thoracic spine is mandatory (Fig. 3). In the patients with coexisting lumbar and cervical stenosis (tandem spinal stenosis), history-taking and physical examination are not definitive; a mixture of upper and lower motor neuron findings may exist clinically [18].

A 40-year-old male patient presented with abnormal gait and low back pain. (A) Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging shows degenerative disc disease in L5–S1 and L3–L4 levels. (B) He was treated with posterior spinal fusion L4–S1, but clinical complaints continued. (C) Later work-up detected cervical spine ependymoma as a main cause of the disability.

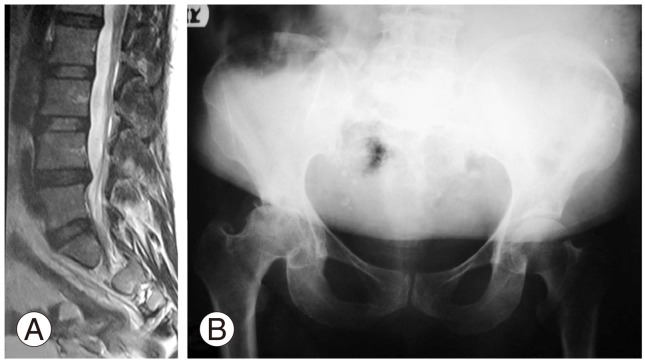

Another clinical entity that can appear similar to LDH is degenerative joint disease of the hip (coxarthrosis) [19]. These patients usually have simultaneous lumbar spondylosis associated with LBP. SLR testing is painful and the clinician can easily mistake it with sciatalgia (Fig. 4). On the other hand, paresthesis does not constitute a reliable criterion for LDH. Paresthesis that is usually associated with LDH has a dermatomal distribution and this is contradictory with disseminated paresthesis in peripheral neuropathy including diabetes mellitus, which usually has a stocking-and-glove pattern [20]. In dealing with a patient presenting with polyneuropathy, excessive alcohol consumption, connective tissue diseases, nutritional deficiencies, and liver or kidney failure should also be considered [21].

A 60-year-old diabetic female presented with a pain in back and right lower extremity. She also complained of limb paresthesis. Straight leg rising testing was positive. More careful physical examination revealed limited right hip range of motion. (A) Magnetic resonance imaging scanning showed a degenerative disc at L4–L5 without significant stenosis. (B) Plain pelvis radiography detected osteoarthritis of the right hip, which was the main pathology of the patient.

Foot drop is another clinical presentation that should be investigated carefully. L3–L4 and L4–L5 LDH with associated L4 and L5 nerve root compression can create weakness in the tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis longus muscle, respectively, and result in foot drop. Peroneal nerve palsy can mimic exactly this clinical picture. Active abduction of the ipsilateral hip joint, indicates intact L5 nerve root and helps to differentiate a central (nerve root compression) from a peripheral cause (deep peroneal nerve lesion), electrophysiologic testing (nerve conduction velocity and electromyography) is also confirmatory [22].

The most common complication of lumbar discectomy is re-herniation with incidence of 5% to 15% depending on study referenced [23242526]. Although recurrent LDH does not necessarily equate with re-operation, in approaching a patient with recurrent LDH the surgeon should differentiate re-herniation from postoperative scar. The first may need re-operation while surgical intervention is contraindicated in the latter. MRI scanning with a contrast material like gadolinium creates scar enhancement and helps in differentiating the two. In the cases with recurrent LDH, gadolinium cannot enhance the disc itself but enhances its peripheral fibrosis (rim enhancement) [27].

Beware of Wrong Patient

There is a strong and well known relationship between outcomes of lumbar disc surgery and psychiatric status of the patients [282930]. Existence of preoperative anxiety is a poor prognostic factor for the perseverance of pain after surgery for LDH [31]. Therefore, secondary gains and/or underlying psychological issues in cases with LDH are a concern.

Many questionnaires assess the psychiatric status of patients. These include the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) and Distress and Risk Assessment Method (DRAM). All the questionnaires address the important effect of underlying psychogenic factors in surgical outcomes [3233]. Therefore, preoperative detection of a patient's mental health problems is a priority. For this, some authors rely on their own experience. As a cautionary note to this approach, a study conducted in United Kingdom reported that compared with the DRAM questionnaire spinal surgeons were able to correctly detect underlying mental disorders in only 26% of cases [34].

Beware of Wrong Level

In those patients with associated lumbosacral transitional vertebra (sacralization of L5 and lumbarization of S1) or disc herniation at a level other than L5–S1, wrong level spine surgery may occur. Using surface landmarks, careful attention to the pelvis and spine plain radiographies and MRI scanning and, eventually, performing intraoperative fluoroscopy after wound dissection with the markers docked against the vertebrae (dissector under lamina, pinpointing to the pedicle, clip on the spinous process, etc.) should be done. This approach can correctly and reliably identify the proposed level and effectively prevent this nightmare in spine surgery [3536].

Beware of Wrong Side

As most of the spinal procedures are carried out in prone positioning, left and right side of the patient may be mistaken. To avoid the pitfalls of the right and left of the patient, preoperative surgical site marketing with a large black marker on the ipsilateral buttock is strongly recommended [37].

Beware of Wrong Tactic

It is very important that the type of surgery should be selected according to the type of the disease, evidencebased medicine, existing facilities, and experience of the surgeon. Although a variety of treatment modalities exist for disc surgery, the standard operation currently recommended for simple LDH is microscopic partial discectomy [38]. Laser disc surgery is a relatively effective and safe manner to treat broad base, bulged or even protruding disc that still contains LDH [39]. This minimally invasive surgery does not have any place in treatment of extruded or sequestrated (non-contained) LDH. It is also contraindicated in the patients with underlying spinal instability like spondylolysis and can create iatrogenic spondylolisthesis [40].

Beware of Wrong Protocol

Wrong protocol in approaching the patients with LDH can be classified into preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative stages, although according to the specific surgical technique it may be somewhat varied. Wrong preoperative protocols comprise inappropriate patient preparation for the surgical procedure (failure to inform the patient of the possible complications, failure to discontinue especial analgesics prior to surgery, such as aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), improper patient positioning to protect the sensitive organs like the eyes, peripheral nerves, and testicles in male patients, and failure to take the necessary measures for full dependence of the abdomen to reduce epidural veins engorgement. Nowadays, there is no hard evidence to support routine preoperative hair removal in spine surgery [414243].

Wrong intraoperative protocols include using a non-standard suction tube with rough edges, advancing discectomy instruments more than 2.5 to 3 cm from the posterior disc border, rush in the process of surgery, and harsh usage of surgical instruments [44]. Postoperative wrong protocols comprise inappropriate rehabilitation, improper timing for returning to previous job, failure to change harmful patient's life style (like frequent exposure to strenuous physical activity at work) and gaining appropriate body mass index [4546].

More Detailed Procedure Does Not Necessarily Mean more Effective

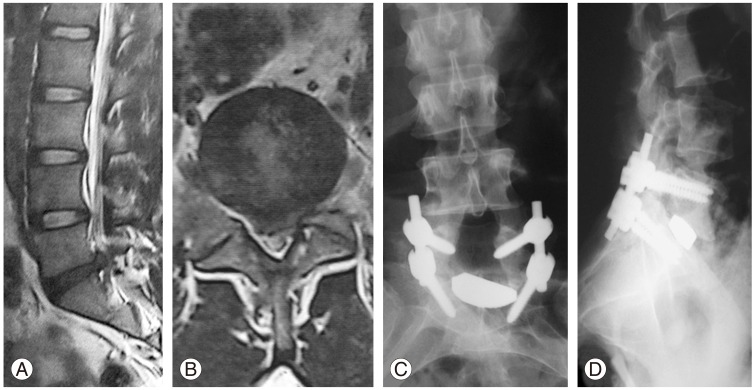

In the surgical approach for a patient with a spine problem, the general rule is that the preferred surgical intervention is the one with the least invasion and greatest benefit. A complex detailed surgery is not necessarily more effective. Performing a long complicated operation, such as transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with pedicular screw and rod fixation for simple LDH not associated with Modic endplate changes, can be inappropriately complex for the intended goal (Fig. 5). The procedure of choice for simple LDH is partial microscopic discectomy, preferably with minimally skin incision. Performing additional measures like posterolateral or interbody fusion and instrumentation in order to obtain additional surgical outcome have only been proposed for those herniated discs accompanied with Modic endplate changes and predominantly LBP (Fig. 5) [47].

A 32-year-old man with low back pain and left sciatic pain. (A, B) Sagittal and axial magnetic resonance imaging scans showed extruded left sided simple L5–S1 lumbar disc herniation. (C, D) Plain postoperative lumbosacral radiographs of the same patent underwent transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion and fixation.

Stand-alone cage in surgical treatment of LDH for avoidance of future intervertebral space collapse may be associated with significant complications including intractable pain or neurologic deficit due to pseudoarthrosis, cage migration, or settling, and therefore can be augmented with some forms of anterior or posterior spinal fixation [48]. On the other hand, unnecessary spinal fusion especially anteroposterior fusion and instrumentation can significantly increase the risk of infection, adjacent segment disease, length of hospital stay, intraoperative blood loss, duration of operation, and cost. In the meantime, existence of a common interest in treating surgeons and commercial companies can exacerbate this scenario and create a long-time disable and miserable patient (Fig. 6) [49].

A 35-year-old female presented with chronic low back pain and recent right sciatica without significant neurologic deficit. (A) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan revealed L5–S1 disc herniation. (B, C) Postoperative plain anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the lumbosacral spine showed L5 laminectomy, while fusion and fixation extended from L3 to S1. (D) Extensive unnecessary instrumentation is shown in postoperative MRI.

Conclusions

LDH is a common spinal disorder that usually favorably responds to conservative treatment. In those cases with refractory complains, surgical intervention may become obligatory. Although, lumbar discectomy is the most common and easiest spinal procedure carried out by orthopedic surgeons or neurosurgeons, it can be associated with catastrophic complications and long-term disability. Appropriate patient selection with proper surgical planning can play the most important role in improving surgical outcome and avoiding complications.

Notes

Conflict of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.