Introduction

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of the spine are rare and unpredictable. GCT comprises less than 5% of the primary bone tumors of the spine [1]. It occurs predominantly in sacrum in the axial skeleton. Being an aggressive bone tumor, it can spread locally/multifocally and distantly, mainly to the lungs with a higher chance of recurrence following surgical excision [2].

Although spinal GCTs are rare, recurrences are often seen. Recurrence rates of 28%, 33.8%, and 42% have been reported [345]. The likelihood of recurrences increases with the length of postoperative follow-up. Treatments of recurrent tumors are usually unsuccessful in long-term follow-up, even if treatment is aggressive. Given that most reported follow-up durations are 5–6 years, statistics on recurrence rates are less reliable [56]. Vigilance regarding recurrences during a protracted follow-up is needed, as is a better understanding of risk factors to prevent recurrence.

In this article we report recurrent GCTs with a minimum 10-year follow-up since the last surgery. The study highlights challenges in management of recurrent spinal GCTs, risk factors for recurrence and recurrence patterns.

Materials and Methods

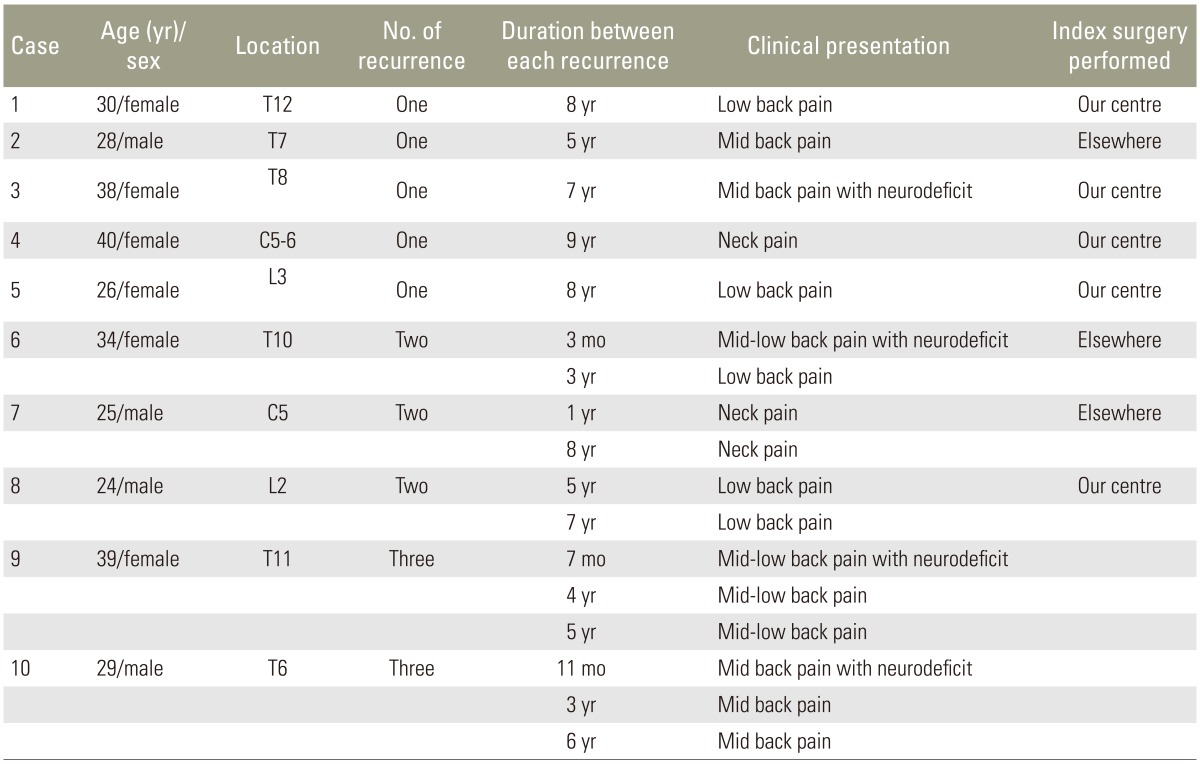

We retrospectively analyzed 10 patients (six females, four males) with recurrent spinal GCTs identified from 226 surgically managed spinal tumors. Six patients had GCT in the thoracic spine, two in the cervical spine and two in the lumbar spine. A total of 17 surgeries were performed in the 10 patients for spinal recurrence. Of these, five patients had their first surgery performed at our tertiary care hospital and presented to us with late spinal recurrences. The other five patients underwent their first surgery elsewhere, were then referred to us for the management of recurrence. All patients presented to us with unrelenting pain with or without spinal instability and spinal cord compression. Four patients had significant neurologic deficits (Frankel grade C=02, Frankel grade D=02) with bowel and bladder involvement.

Although preoperative tissue diagnosis in the form of computed tomography (CT) guided biopsy is a standard care today, a positive pretreatment biopsy was not done in any of our patients. Preoperative fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was inconclusive in the five patients first operated on at our hospital. We operated on the basis of radiological suspicion, with histological confirmation on intraoperative frozen sections. These cases had their first surgery between 1990 and 1995, a period when CT guided biopsies were not performed in our surgical set-up. Thus, frozen section seemed like a better plan than a separate open biopsy. The other five patients, who had their index surgery elsewhere and who presented to us with recurrence had the histopathology report of their previous surgery available. Digital subtraction angiography (DSA) with vascular embolization was done in all patients preoperatively.

1. Surgical details

Anterior spinal surgery was preferred in patients who had recurrence with significant extra-compartmental and intraspinal spread, without any spinal deformity. Patients who had recurrence with significant extra-compartmental and intraspinal spread with spinal deformity due to vertebral collapse/spinal instability were considered for combined, single stage, posterior and anterior spinal surgery. Patients who had recurrence with significant extra-compartmental and intraspinal spread, presenting with strategically located, minimal tumor tissue causing spinal cord compression were considered for posterior surgery alone. In this minority of patients, the recurrent tumor tissue could be easily removed by a wide posterolateral decompression or transpedicular decompression. All patients received postoperative radiotherapy in divided doses that were optimum for the particular patient, in consultation with an oncologist at each recurrence. These patients were followed up regularly at 3, 6, and 12 months in the first year and annually thereafter. Roentgenography during each follow-up visit and CT scans during the annual follow-up examinations were studied for the presence of tumor recurrence and to assess spinal instability.

Results

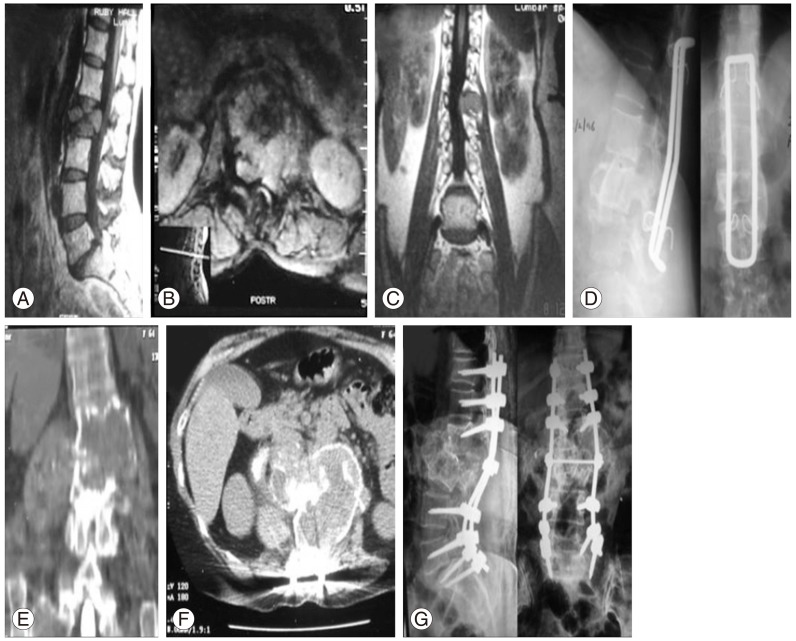

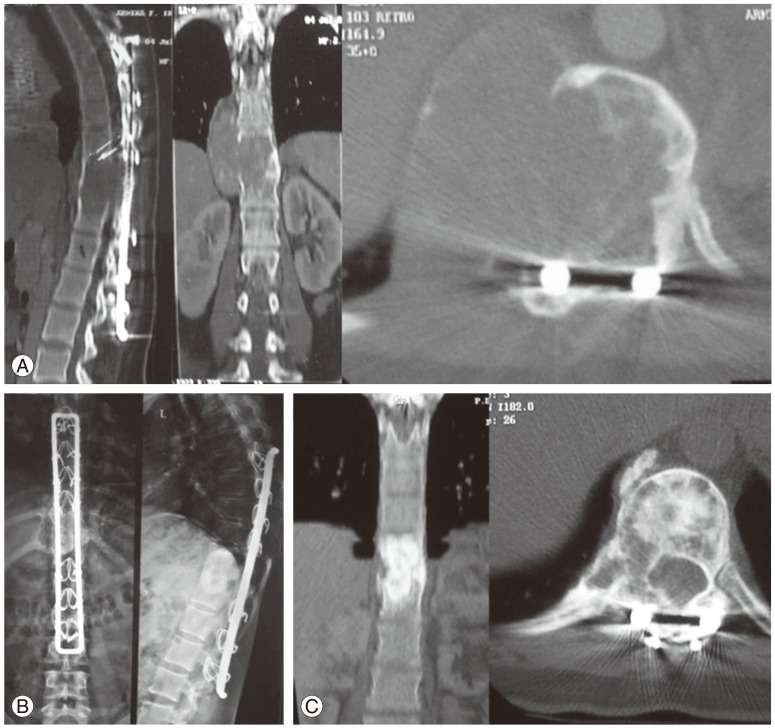

The average age of the patients at time of index surgery was 31.3 years (range, 25–40 years). The average recurrence free interval (six recurrences) in patients operated on in our tertiary care hospital was 7.3 years (range, 5–9 years) compared to patients who had their primary surgery elsewhere (40 months; range, 3–96 months). The minimum postoperative follow-up period after the last revision surgery was 10 years, which represents the longest recurrence-free interval yet reported. All four patients with neurologic deficits improved to Frankel grade E in the immediate postoperative period. Patients with preoperative neurologic deficit of more than Frankel grade C took more than 3 months to improve to Frankel grade E. Postoperative radiotherapy was given in all patients. The patients who were operated elsewhere and presented to us with recurrence had not received radiotherapy after their index surgeries. There were no major complications. Two patients had superficial wound infections that healed uneventfully. There were no malignant transformations. However, there were recurrences (Table 1). Cases of double and single recurrence are presented in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively.

Discussion

Asymptomatic occurrence of recurrent spinal GCTs are uncommon. Recurrent spinal GCTs are expansile lytic lesions that most commonly present with local pain due to periosteal stretch [7]. More often, they are detected once neurological deficit evolves. Neurologic deficit can develop due to vertebral collapse/spinal instability, with extra-compartmental intraspinal tumor spread engulfing the spinal cord/nerve root. Spinal instability is mostly due to cortical breach by the tumor leading to pathologic vertebral collapse [8]. All patients in this series presented to us with significant spinal pain and, in four patients, neurologic deficit that warranted resurgery. Spinal pain and neurological deficit in recurrent spinal GCTs is due to advanced lesion with extra-compartmental and intra spinal tumor spread. The diagnostic delays add to late presentation. Hence, spine surgeons often have to resort to marginal or intralesional excision, even though 'en bloc' spondylectomy or total resection of the tumor is considered as optimum surgery.

Radiological diagnosis of tumors that is done in some situations has misguided clinicians often enough for us to recommend a diagnostic biopsy before treatment. Compared to FNAC, a pretreatment CT guided transpedicular core needle biopsy is the preferred method to achieve a histopathologic diagnosis before surgery. An inconclusive preoperative biopsy makes an intraoperative frozen section mandatory [9]. However, the histopathologic grading does not reliably correlate with prognosis [610], and so was not recorded in our study.

GCT is a highly vascular tumor, so surgical site bleeding is highly probable. High recurrence rate following therapeutic embolization necessitates its use only to decrease the operative bleeding [11]. A preoperative DSA-aided embolization of major tumor vascular feeders was done in all patients each time surgery was performed. This not only minimizes blood loss but also gives operating surgeon a dry field for optimal tumor excision. However, this cannot be performed for common vascular feeder, which supplies the tumor as well as spinal cord, due to the warranted fear of spinal cord ischemia [12].

Compared to an autograft, the acrylic cement and metal cage is the preferred modality for anterior column reconstruction, as it provides immediate stability. The frequently used postoperative radiotherapy in GCTs often hampers the strength of autograft construct. GCT can recur in the grafted bone, which is very difficult to diagnose when compared to acrylic cement/metal cage [1314]. GCT recurrence typically presents on radiographs as a thin, hypointense line separating the tumor from acrylic cement/metal cage [15]. In our series, metal cage impregnated with acrylic bone cement was used in the majority of our patients. Fig. 3 shows use of cement following intralesional curettage in case 2.

Thorough intralesional curettage and meticulous excision of tumor tissue is important while excising spinal GCTs. Some tumor tissue is expected to remain; therefore postoperative radiotherapy is obligatory [16]. Irradiation likely converts benign GCTs to malignant ones. This is no longer true with modern radiotherapy techniques like image-guided intensity modulated radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery. By using these techniques a maximum tumor kill can be achieved with optimal safety to nearby vital structures [1718]. In our series all patients underwent an intralesional to marginal margin excision, followed by postoperative radiotherapy. Radiation was given in divided doses for each GCT recurrence till optimum dose was delivered.

Based on our case series, we can draw some conclusions on risk factors and recurrence patterns of spinal GCT. The primary surgery and postoperative treatment is of prime importance in spinal GCTs. The patients who underwent their index surgery at tertiary care centre had fewer recurrences compared to those first operated on elsewhere. Tumor recurrence also depends the on aggressiveness of index surgery. The preoperative definitive tissue diagnosis, preoperative embolization, approach for tumor excision, modality of reconstruction and postoperative radiotherapy is crucial to prevent recurrence. In this series, the duration of recurrence was longer with intralesional index surgery done at our tertiary care hospital. The largest recurrence free interval suggests that intralesional surgery is safer and effective.

Our study has certain limitations. It's a small sample size. However, this can be attributed to rare occurrence of GCT. Also, few (five) cases were operated by different surgeons at primary presentation.

Conclusions

Spinal GCTs are complex and challenging. Meticulous planning is mandatory in view of available resources. Stringent preoperative, surgical and postoperative protocol should be followed at each recurrence. Understanding of risk factors and strict, regular and long-term follow-up are needed to detect recurrences early.