Introduction

With the aging population, the incidence of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCFs) is increasing and becoming a major health-care issue [1,2]. The intravertebral vacuum cleft (IVC) sign in these patients has obtained much attention in recent reports [3-5].

In flexion and extension lateral films, the IVC sign is characterized as dynamic instability or pseudoarthrosis [6,7]. Patients with IVC sign complained of severe pain, especially when they changed positions, and did not respond to bed rest, medication, corset and other conservative treatments. Thus, surgical intervention was recommended [8].

The IVC sign was first reported by Maldague et al. [9] as a sign of ischemic vertebral collapse, then Theodorou [10] and Sarli et al. [11] described the details of this sign. On radiograph, it appears as a transverse, linear or semi-lunar radiolucent shadow. There were many different synonyms for this sign: such as "intravertebral cleft" [5], "linear intravertebral vacuum" [12], "intravertebral vacuum phenomenon" [13], "intravertebral vacuum sign" [14], "intraosseous vacuum phenomenon" [15], "intra-vertebral pseudarthrosis" [7] or "Kümmell disease" [16].

It was also reported that the IVC sign could be caused by long-term corticosteroid therapy, diabetes, arteriosclerosis, alcoholism, pancreatitis, radiation therapy, acute trauma, malignancy, and infection. Since the IVC sign caused by malignancy and infection have different pathogenesis and radiological features [9], the IVC sign caused by malignancy and infection were excluded from our study.

Pathogenesis of IVC

The pathogenesis of IVC was unclear, Maldague et al. [9] first associated avascular necrosis with IVC sign in 1978, they followed up 10 patients with an IVC sign range from one to six years. The histological data of one patient and radiological data of six patients were collected. They presumed that IVC was a specific sign of local bone ischemia. This avascular necrosis theory was also supported by anatomical studies: the vasculature of thoracic and lumbar vertebral bodies arises from paired segmental arteries, posterior central branches to the dorsum of the body supply two adjacent vertebral bodies, while anterior central branches to the ventral of the body supply one vertebral body. Therefore, the blood of the vertebral ventral zone only supplied by the short, branch early anterior central branches, putting theoretical higher risk of vascular insufficiency for the vertebral ventral zone. The weak blood supply of vertebral ventral zone was also proved by Ratcliffe [17].

Van Eenenaam and el-Khoury [18] reported a patient had a normal computed tomography (CT) scan and plain film at 3 weeks after initial back injury, while the bone scan showed an increased radionuclide uptake. The vertebral body was collapsed with IVC sign 9 weeks after injury. They considered bone scan as a sensitive imaging tool for early diagnosis of ischemic necrosis and they supposed that the avascular necrosis at 3 weeks after injury caused vertebral body collapse afterwards. Hermann et al. [19] reported a Gaucher's disease type 1 patient exhibiting IVC sign in the vertebral body, and the accumulation of glycosyl ceramide in Gaucher's cells could involve bony artery; therefore, this case could be additional evidence for avascular necrosis theory. The avascular necrosis theory was also supported by Bhalla and Reinus [12], and other authors [20].

Not all of the authors agree with the avascular necrosis theory as the pathogenesis of IVC. Kim et al. [3] analyzed 67 patients with IVC sign and noted that the IVC sign occurred predominantly in the thoracolumbar junction (81%). For the wide activity and great load of the thoracolumbar junction region, they concluded that biomechanics also played an important role in the pathogenesis of IVC sign. According to recent literatures, osteoporotic vertebral fractures with or without IVC sign most commonly occur in the region of the thoracolumbar junction, consistent with the biomechanics theory. Osteoporosis was also considered as a factor that put the higher ratio ischemia of the vertebral body, because of decreased osteoblasts of these patients [21]. The study also found the significant inverse correlation between the bone mineral density (BMD) and the frequency of IVC sign [22].

Armingeat et al. [23] prospectively evaluated the presence of radiological findings regarding 15 patients with IVC over a 6-year period. He noted that 13 of them had intradiscal vacuum cleft adjacent to the fractured end-plate, and communication between the intradiscal and intravertebral collections was observed in 5 patients. They suggested that the gas may migrate from the disk to the vertebral body, and the gas contained about 90% to 92% nitrogen.

Kümmell's Disease or Not?

Kümmell's disease was described by Dr. Hermann Kümmell [24] in 1895, characteristized as initially asymptomatic for weeks to months, and delayed post-traumatic osteonecrosis. It was divided into 3 stages: 1) Initial injury to the spinal column attended with a varying degree of surgical shock; 2) Relative comfort in which the patient is able to carry on his occupation; 3) Several weeks or months after injury, or even two or three years, an angular kyphosis develops with recurrence of pain, which is either localised over the spine or radiates over the extremities [25]. Moreover, Hosford [26] and Steel [27] described Kümmell's disease as five stages.

The diagnosis of Kümmell's disease was completely dependent on the clinical presentations at that time, lacking objective test evidence before the discovery of radiography. The clinical presentations of some patients with IVC sign were so similar to Kümmell's disease, and some authors regarded the IVC sign as "Kümmell's sign", patients with IVC sign were diagnosed as Kümmell's disease [28-30], arousing fierce controversy.

Young et al. [31] argued that Kümmell's disease is distinguished from the typical osteoporotic compression fracture with IVC sign. In 2002, they reviewed the English language literatures since the 1950s and felt that only 5 cases met the diagnostic criteria set out by Dr. Hermann Kümmell. With the same view held by Swartz and Fee [16], they argued that eponymous diagnosis should be restricted to those individuals whose X-ray imaging around the time of the trauma was unremarkable, but later developed vertebral body collapse, and concluded that there were at most 10 Kümmell's disease patients in the past 30 years of literatures.

In fact, as reported by Hosford [26]: Kümmell's diseases was not rare as Kümmell first described six cases in his paper while other authors had reported many cases since 1895. Another fact was that Verneuil had described the same syndrome in 1892, which was earlier than Kümmell. In some instances it had been named as "Kümmell-Verneuil disease". The diagnosis of Kümmell's disease only based on clinical presentation, pathogenesis and imaging characteristics of Kümmell's disease were not described by Dr. Hermann Kümmell originally. As we know, medicine is the process of exploration. With the improvement of diagnostic methods, the standard diagnosis of diseases trend to based on etiological evidence. The pathogenesis and imaging character of Kümmell's disease that described by Dr. Hermann Kümmell originally was unclear, it cannot exclude the possibility that different etiologies between six patients reported by Dr. Hermann Kümmell and the Kümmell's disease reported by other following authors. The clinical symptoms of some patients with IVC sign were very similar to Kümmell's diseases, thus it is reasonable for some modern authors to regard the IVC sign as "Kümmell's sign", and diagnose some OVCFs patients with IVC sign as Kümmell's disease.

If vertebral avascular osteonecrosis with IVC caused by osteoporosis or corticosteroid therapy or other conditions were excluded, the real existence of Kümmell's disease will be questioned. No one can be sure if Kümmell's disease is reality or a myth. There are only two choices: call the vertebral avascular osteonecrosis with IVC as Kümmell' disease or let the name of Kümmell's disease disappear from textbooks. I believe we will change the former to commemorate the great Dr. Hermann Kümmell.

Images of the IVC Sign

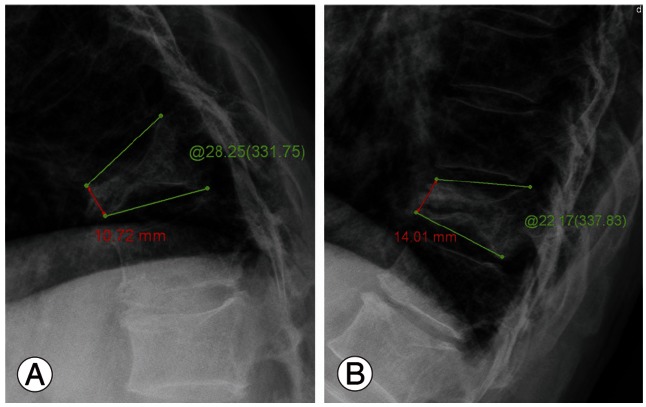

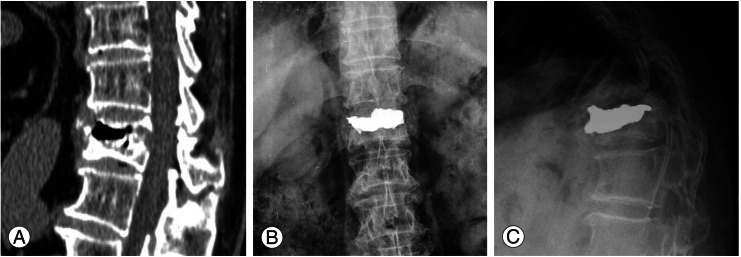

After Maldague et al. [9] reported six cases who exhibited the IVC sign in radiographs, many studies described the details of this sign [10,11,20,32], To sum up: 1) The IVC sign appears as a transverse, linear or semi-lunar radiolucent shadow in plain radiographs (Fig. 1). In addition, lateral views may help distinguish between an intraosseous, intervertebral, or bowel location of the lucency; the supine lateral views are more efficient to detect the IVC sign; 2) The sign could also be seen on CT scans, and appears more heterogeneous and irregular (Fig. 2); 3) On magnetic resonance (MR) images, the sign is generally seen as low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, low signal intensity or high signal intensity on T2-weighted images depending on the content of gas or liquid in cleft.

For patients with an acute osteoporotic fracture, fluid will fill the cleft from the adjacent bone marrow edema when patients are in the supine position just for 1 or 2 minutes [4]. In some cases, fluid was initially already present at the beginning of the MR examination. For patients with a fracture history of more than 3 months, the time of fluid collection is more than 20 minutes [33]. Therefore, patients with an acute fracture often show high signal intensity on T2-weighted images while patients with a longer fractured history often show lower signal intensity, because it is not enough time for fluid collection before MR examination.

The typical IVC sign is distinguished from the representation of malignancy in plain radiography, CT or MRI [12,34], but they are often inadequate in distinguishing the distinction between malignancy and benign compression fractures. Thus, biopsy is needed for further diagnosis.

1. Surgical intervention

Patients with IVC sign usually have severe back pain and do not respond to conservative treatments such as bed rest, medication and orthosis. Surgical intervention is recommended [8]. Percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) is the main method used for these patients [5,32,35], and percutaneous kyphoplasty (PKP) is also reported by some authors [36,37].

2. Pain relief

Chen et al. [38] reported 27 patients with IVC sign, all of them had content pain relief immediately after PVP, and Krauss et al. [39] reported that patients with IVC sign had the same pain reduction as patients without it. The same result was reported by Lane et al. [5]. Jang et al. [8] noted that 8 in 16 patients had complete pain relief, while 6 patients had moderate pain relief and 2 patients had no significant pain relief. This concludes that PVP is a reasonable procedure for these patients.

However, not all studies shared an optimistic view of PVP. Ha et al. [40] reported that the pain reduction of patients with IVC after PVP was less than those without cleft. Furthermore, Peh et al. [41] reported that 4 cases in 18 patients and Wiggins et al. [42] reported that 5 cases in 15 patients had no improvement or even aggravated back pain after PVP. The explanation of inadequate pain relief may be a predominant filling of the IVC, and the remaining vertebral body will remain unsupported and untreated. Most previous studies treat patients with IVC sign by PVP, and few authors manage them with PKP. The pain relief after PKP was not significantly different with PVP [37].

3. Correction of kyphotic angulation

PVP could correct kyphotic angulation (KA) of IVC patients more effectively than those without IVC sign [32,39,43]. The IVC was similar to pseudarthrosis (Fig. 3), and auto-reduction was obtained when patients were in the prone position. Preoperative kyphosis was reported as another influential factor regarding the degree of kyphosis correction after operation [44]. Preoperative dynamic instability seemed to be a good indicator of the potential to restore vertebral height [6,45]. PKP was reported to be better at correction of KA and restoration of vertebral height for patients with IVC sign [37,46]. In vitro study [47] likewise found that height was better restored after kyphoplasty compared to vertebroplasty.

Spinal deformation was related to functional limitation [48]. Thoracic compression fractures and kyphosis were related to pulmonary function decreases and pulmonary deaths [49]. Spinal deformity was also speculated as an independent risk factor of hip fracture [50]. These findings suggested that restoration of vertebral body height and correction of KA is an important component. However, Kim et al. [35] reported that KA correction of >5° could be a poor prognostic factor. They presumed that patients with too much correction of KA resulted in more instability of the fractured segment, more paravertebral soft tissue or ligament injury, and had persistent pain in the first month after operation.

4. Cement leakage and pulmonary embolism

A comparative study [40] showed that cement leakage after PVP was observed in 9 out of 12 vertebrae cases with IVC sign (75%), and higher than 24 cases in 58 vertebrae without it (32.6%). Likewise, Nieuwenhuijse et al. [51] identified the IVC sign on MRI as additional strong risk factors of cement leakage. However, Krauss et al. [39] reported that the incidence of cement leakage was lower for vertebral bodies with IVC sign than those without it. Another comparative study [52] found no statistically significant difference regarding the incidence of cement leakage between vertebrae with IVC (53 of 107 vertebrae, 49.5%) and those without IVC (78 of 193 vertebrae, 40.4%) after PVP. The result was consistent with that of Jang et al. [8]. Wang et al. [37] reported that the incidence of cement leakage was lower for IVC patients after PKP, the lower pressure cavity created by PKP permits cement injected readily, and lowers the incidence of leakage.

The cement leakage ratio was not only influenced by the existence of IVC sign, but was also influenced by factors such as the viscosity of cement, the velocity and volume of injection, the inner pressure and the morphology of fractured vertebrae [51,53]. In the majority of cases, cement leakage is harmless and requires no further therapy. But caution should be taken to avoid intervertebral disk leakage and pulmonary cement embolism.

Tanigawa et al. [52] noted that the cement leakage into the intervertebral disk was significantly more frequent in vertebrae with IVC sign. The IVC and intradiscal vacuum cleft often co-exist, and a communication channel could be observed between them [23]. Cement was readily leaking into intervertebral disk via the channel. Intervertebral disk cement leakage is often asymptomatic, however, it was reported as one risk factor of new fracture at adjacent vertebrae [54,55]. The postoperative radiograph of a typical patient demonstrating the coexistence of IVC and intradiscal vacuum cleft in our department showed cement leak into the intervertebral disk, and an adjacent vertebral body fracture at 3 months after the first operation (Fig. 4).

Since X-rays and CTs were not conventionally performed on patients after PVP or PKP, and most pulmonary embolism patients were asymptomatic, many pulmonary cement embolisms remained undetected. A literature review demonstrated that the risk of pulmonary embolism ranged from 3.5% to 23% [56]. Although asymptomatic patients with a peripheral pulmonary cement embolism required no treatment besides clinical follow-up, sometimes the pulmonary cement embolism demonstrated fatal complications [57]. The study also indicated [58] that the incidence of cement embolic events regarding patients with IVC were significantly less than patients without cleft. Therefore, the IVC was regarded as a protective factor for cement embolic events.

Conclusions

The IVC sign is commonly observed in OVCF patients. Avascular necrosis theory is the most supported as a pathogenesis of IVC sign. Biomechanics and osteoporosis are two other important contributors. The sign appears as a transverse, linear or semi-lunar radiolucent shadow in plain radiographs. The extension lateral view, CT scan and MR image were reported as more effective to detect the IVC sign. The Kümmell's disease with IVC sign reported by modern authors was incomplete consistent with the syndrome reported by Dr. Hermann Kümmell. However, no matter what etiologies cause vertebral compression fracture in patients with IVC sign, this sign is regarded as dynamic instability of the vertebral body that results in severe back pain. PVP can stabilize the vertebral body, relieve back pain, and restore vertebral body height and correct KA, and is thus recommended for these patients. PKP seems to be more effective at correction of KA and lower cement leakage in the limited literatures. Although the safety of PVP or PKP was reported, cement leakage into the intervertebral disk or pulmonary cement embolism should be taken cautiously.